Scalpels and sketches

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 04 issue 06 :: Jul 2025

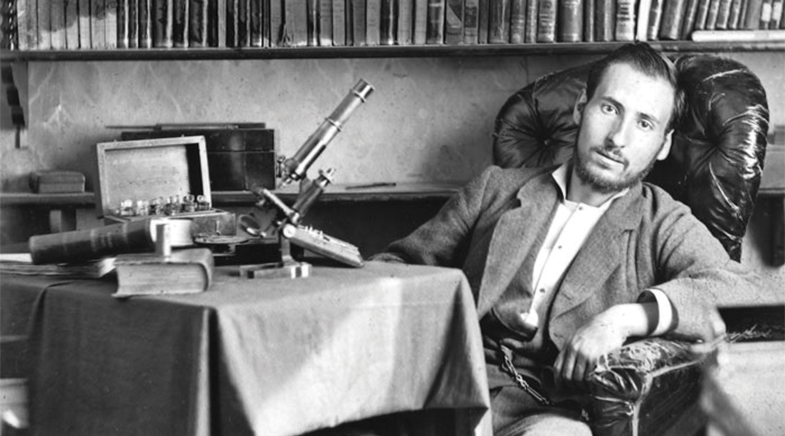

Spanish anatomist Santiago Ramón y Cajal made fundamental discoveries in neuroscience.

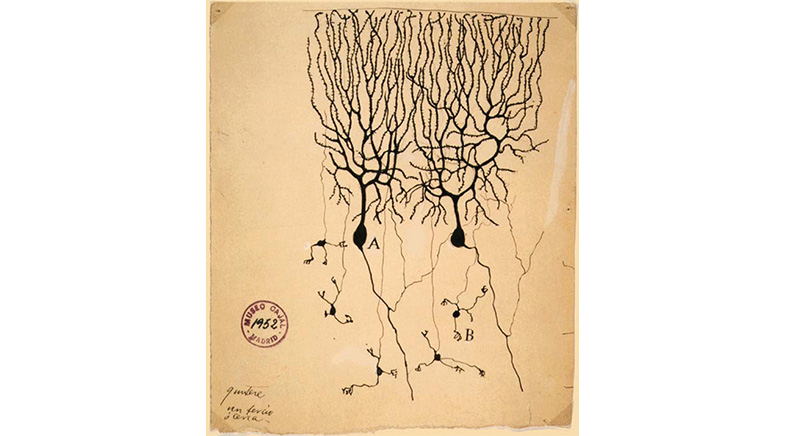

Holding a thin piece of brain tissue from a three-day-old pigeon embryo between his left thumb and forefinger, Santiago Ramón y Cajal sliced it deftly using a razor blade. He dipped the slice twice in a silver nitrate solution and slid it under a microscope. He saw a thin black line travelling down a long path before branching into a tree-like shape. One tiny branch from the tree snaked towards nearby cells on the slide, getting as close as it could without touching them. He picked up a pen and began to draw what he saw.

Growing up, Cajal wasn't always interested in anatomy. Born in rural Spain in 1852, he was a rebellious boy who once blew up his neighbour's gate and scaled buildings to steal sweets. Art was his passion: he would scribble and paint on every surface he could find. "A smooth white wall exercised upon me an irresistible fascination," he wrote (bit.ly/cajal-art). Desperate to steer his son towards medicine, his father once dragged him to a cemetery to pick up and analyse bones. Cajal eventually gave in, agreeing to "exchange the magic palette of the painter for the nasty and prosaic bag of surgical instruments".

After a short military stint in Cuba, Cajal completed his medical degree in 1877. He first focused on studying inflammation and infectious diseases but then turned his attention to the nervous system. At that time, scientists believed that the nervous system was a "reticulum" – a continuous network formed by physically connected nerve cells. But Cajal wasn't convinced.

HOMETOWN HERO

After Cajal won the Nobel, he was widely celebrated in Spain. Students clapped when they saw him, streets were named after him, and a letter with just the name "Cajal" could supposedly find its way to him. For his part, Cajal trained and mentored several scientists and encouraged youngsters to take up science through his lectures and writing. He also advocated for reforms in education and urged politicians to support scientists.

PHOTO: WIKIPEDIA

In 1887, when working at the University of Barcelona, a colleague showed him slides with some neurons stained using a technique developed by Italian scientist Camillo Golgi. Golgi's technique, developed over a decade earlier, wasn't perfect. Cajal improved it by double-dipping the tissues and changing the dipping duration for different types of tissues. Rather than adult human cadavers, he took brain slices from bird and animal embryos, which had less tangled and less protected nerve cells.

His research and detailed sketches showed that nerve cells were individual units that didn't touch each other but talked across gaps, later termed synapses. He described the cells as "mysterious butterflies of the soul, whose beating of wings may one day reveal to us the secrets of the mind". Many scientists were impressed with Cajal's work, but Golgi, who favoured the reticular theory, wasn't. A bitter academic feud erupted between the two, which continued despite the duo jointly winning the Nobel Prize in 1906. Golgi even used his Nobel lecture to criticise Cajal's work. Eventually, other scientists rallied around Cajal's "neuron doctrine".

METAPHYSICAL MATTERS

Cajal was also fascinated by psychological phenomena like dreams and hypnotism. When his wife was in labour with their sixth child, he tried using hypnosis to alleviate her pain. He briefly interacted with people who experienced hysteria. He wrote a manuscript on hypnotism, spiritualism, and metaphysics, but it was lost when the medical centre housing it in Madrid was bombed during the Spanish Civil War.

Cajal also helped identify other parts of neuron structure, like dendritic spines, and hinted at aspects that others would later confirm. Decades after he died in 1934, his intricate drawings continue to find a place in textbooks, classrooms, museums, and exhibitions – and even in the tattoos of many inspired scientists (bit.ly/cajal-tattoo).

Ranjini Raghunath is a Bengalurubased science writer and editor.

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH