India's bumpy road to 'net zero'

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 01 edition 02 :: Jul - Aug 2021

The path to 'net zero' carbon emissions is challenging, and realising it will require a generational shift in technology use.

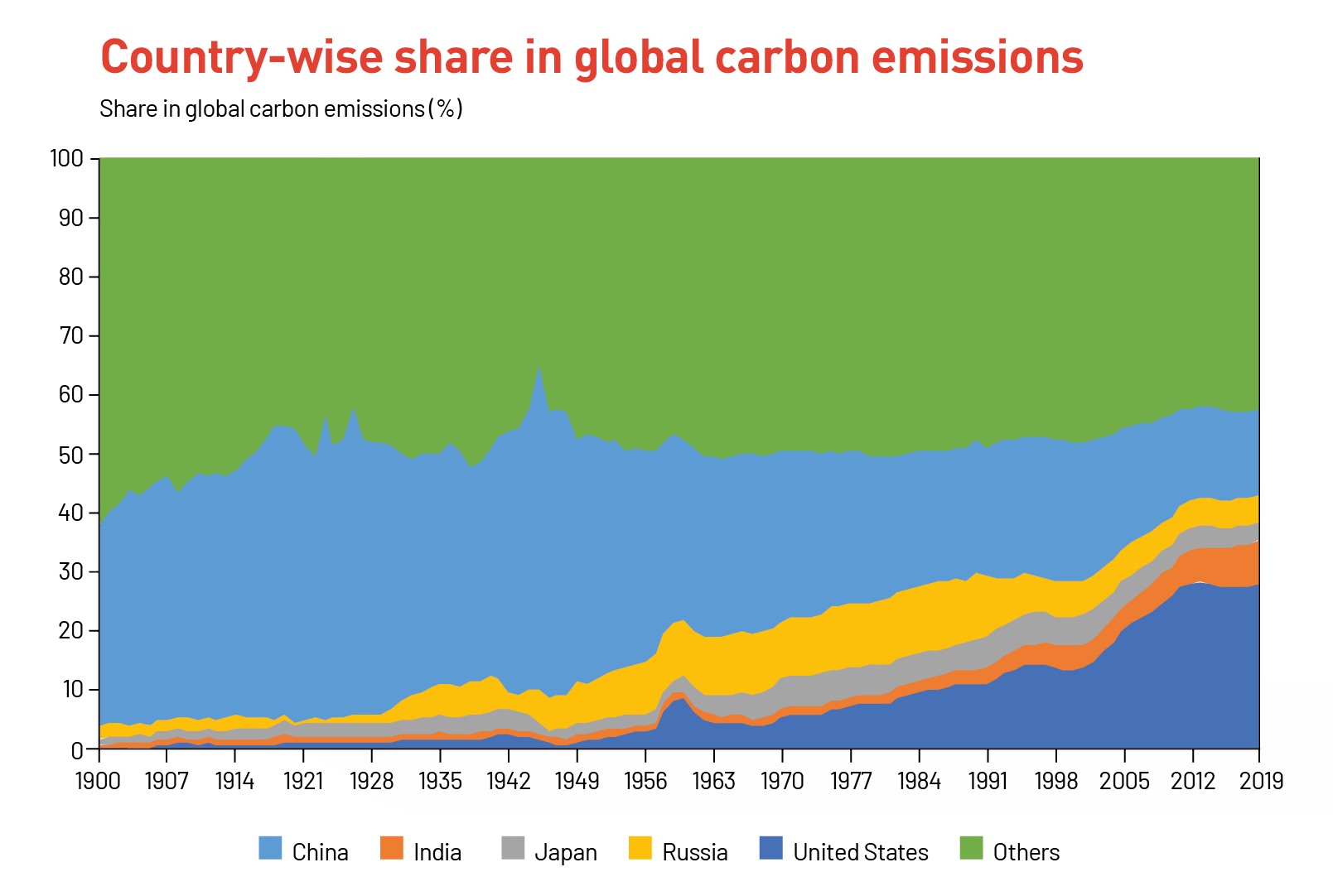

Some 137 countries have committed themselves to becoming carbon-neutral by 2050. China, the world's largest emitter of carbon, has pledged to achieve carbon-neutrality by 2060, and the United States by 2030. India, so far, has not pledged a specific target, but has promised to abide by the Paris Agreement to decrease its emissions intensity 30-35% from 2005 levels by 2030.

Collectively, achieving 'net zero' carbon emissions by 2050 is critical in the effort to limit the rise in global temperatures to 1.5° Celsius, against the current trajectory of 2.1° by 2100. As a developing nation, India faces a severe challenge in managing its carbon emissions while pushing economic growth.

howindialives.com is a database and search engine for public data

INDIA'S CHALLENGE

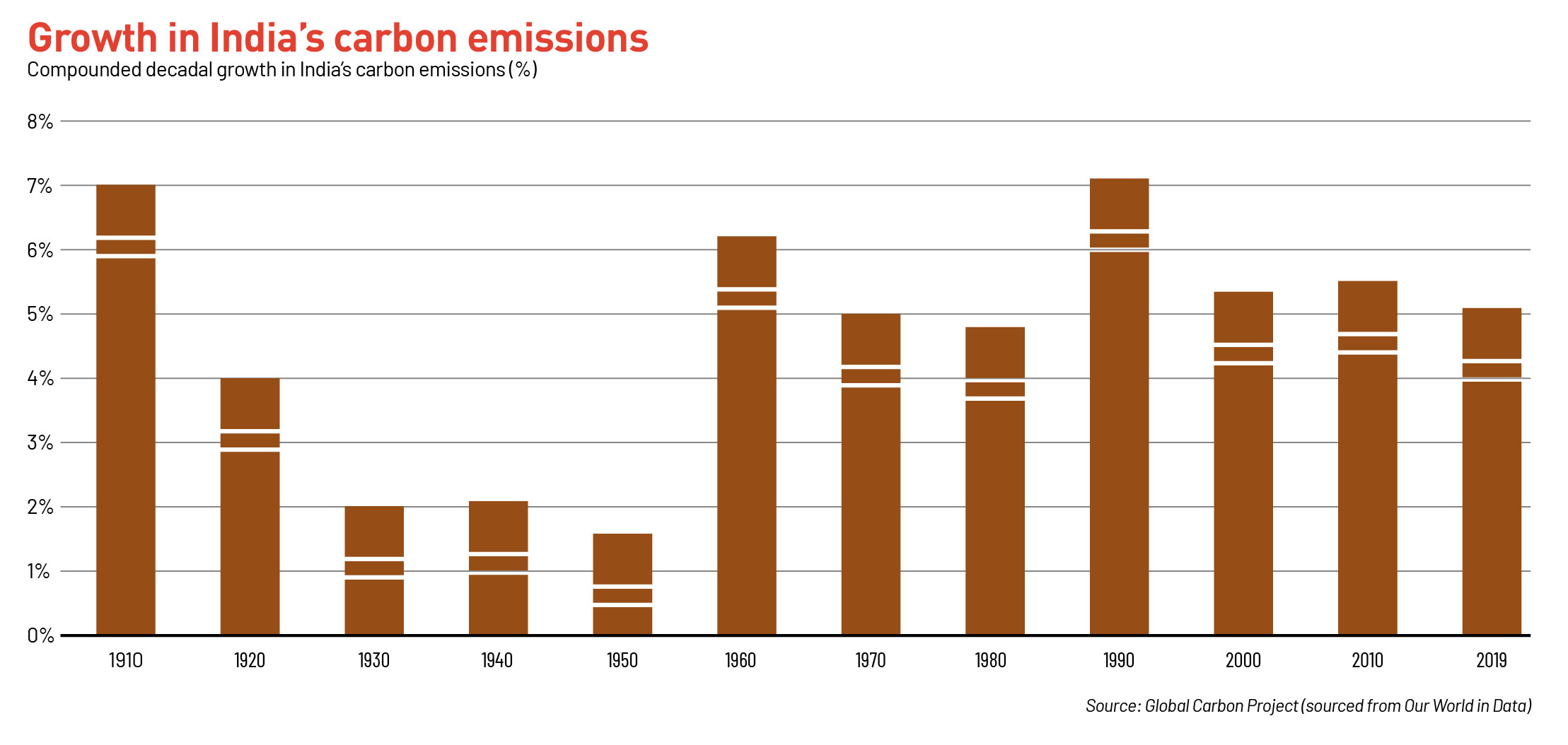

India today accounts for about 7% of total global carbon emissions. This is about one-fourth that of China and half that of the United States. India's carbon emissions have grown at a faster rate since India opened up its economy in the early 1990s and moved to a higher growth trajectory. In the last decade, India's carbon emissions grew at a compounded annual rate of about 5.1%.

SOURCES OF EMISSIONS

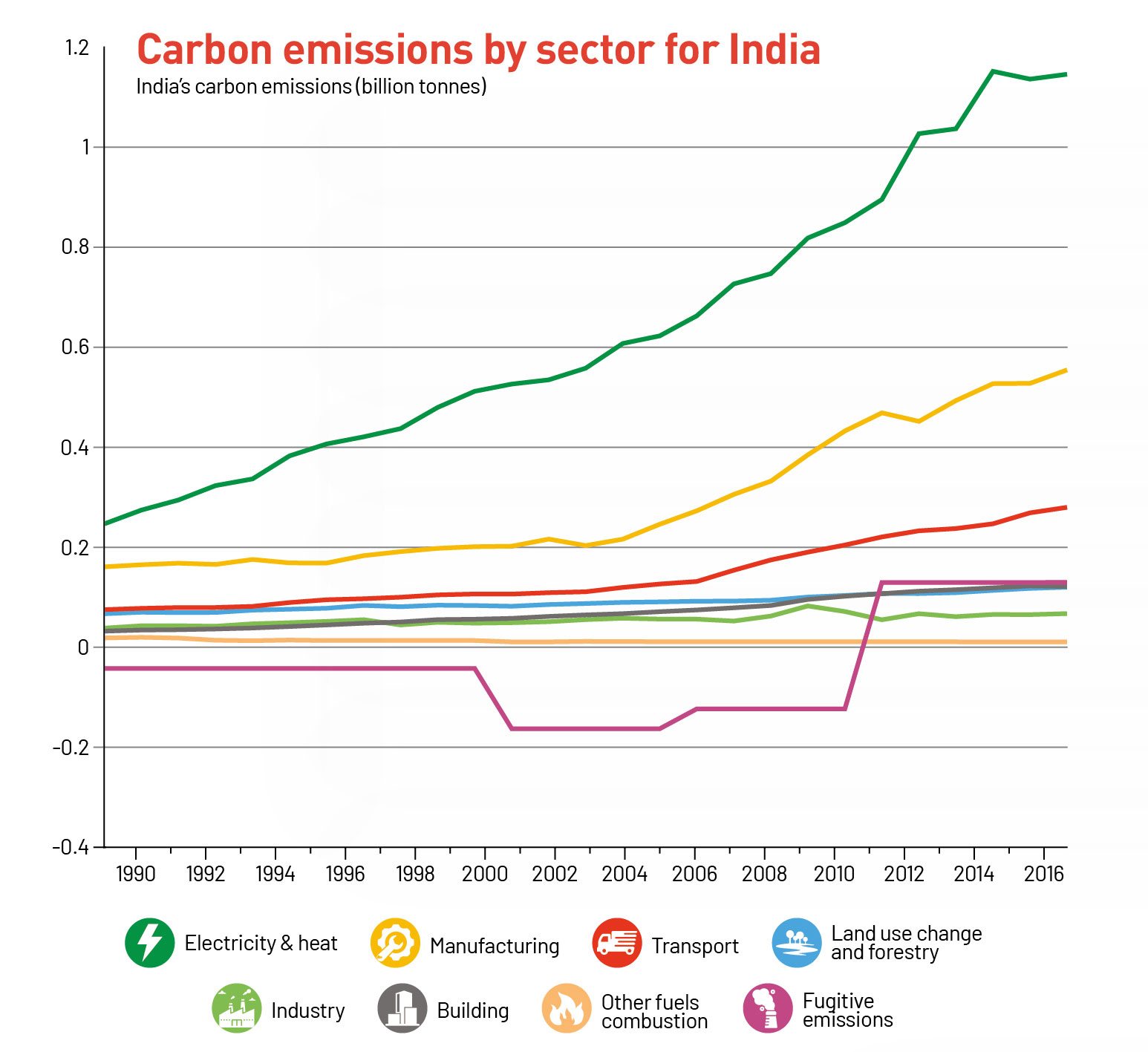

As of 2016, electricity and heat accounted for 48% of India's emissions. This was followed by manufacturing processes (23%) and transportation (11%). In other words, the power sector is the key prism through which to see India's efforts to reduce emissions.

Beyond consumption, there are two levers that countries can use to reduce emissions. The first is exports, as emissions are recorded in the country of consumption, not in the country of production. This construct helped India reduce its carbon emissions by 0.3% in 2019. By comparison, China, the world's largest exporter, offset its emissions by 9%.

The second is forest cover. Forests absorb carbon and create what, in the context of carbon emissions, is called a ‘carbon sink'. Between 1990 and 2010, India was able to reduce its carbon emissions through this source. However, with progressive deforestation and change in land use, this head now accounts for a 5% share in India's carbon emissions.

RENEWABLE STATUS

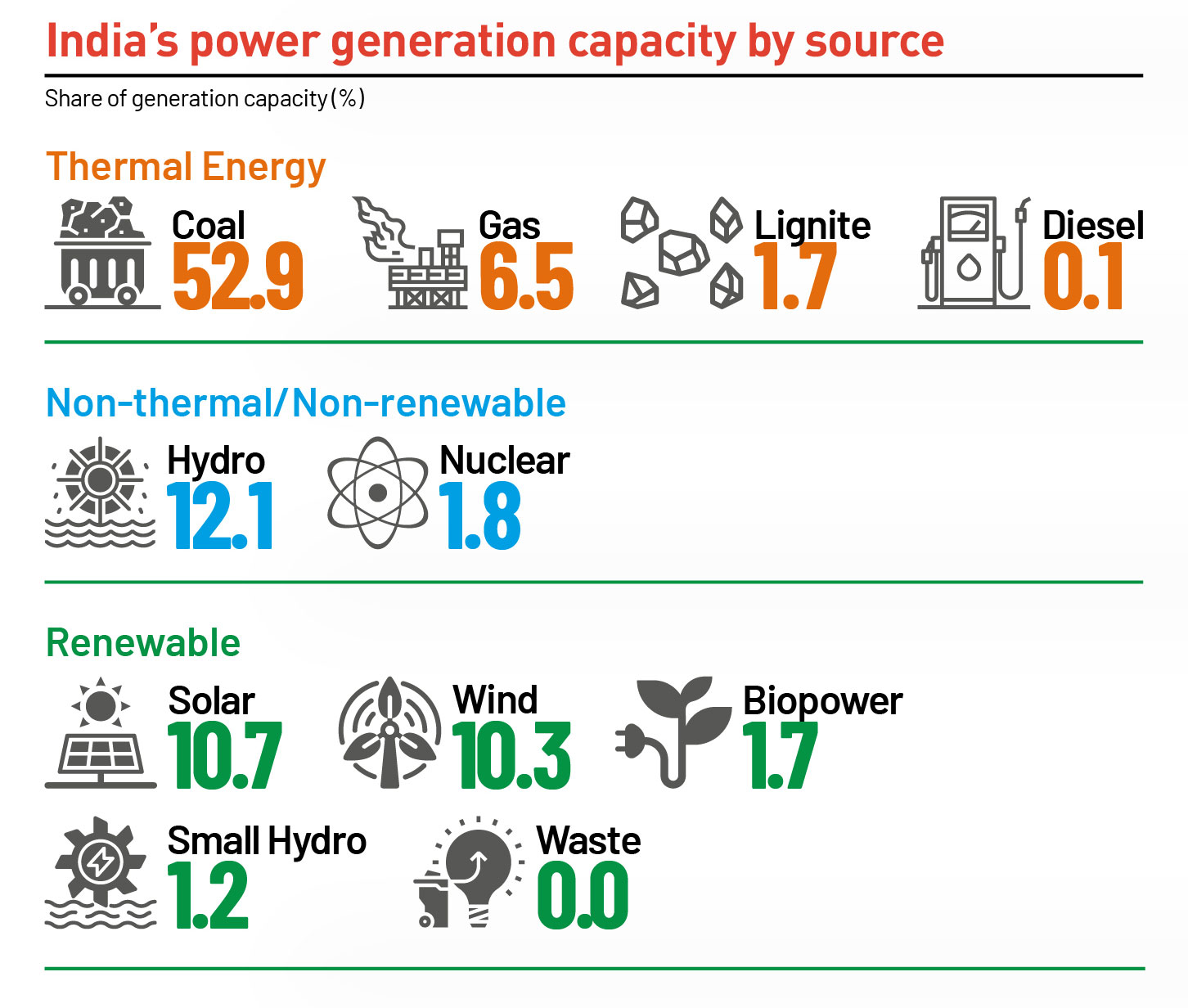

From a source perspective, coal-based sources account for two-thirds of carbon emissions. This has consistently exceeded 60% since 2004, underscoring India's high dependence on coal. It is followed by oil (25%). To achieve carbon neutrality, moving to alternatives for coal and oil is critical.

Renewable sources of energy, like solar and wind, are the alternative. As part of the Paris Agreement, India has pledged to achieve 40% of its electricity capacity through renewable sources by 2030, against 25% currently.

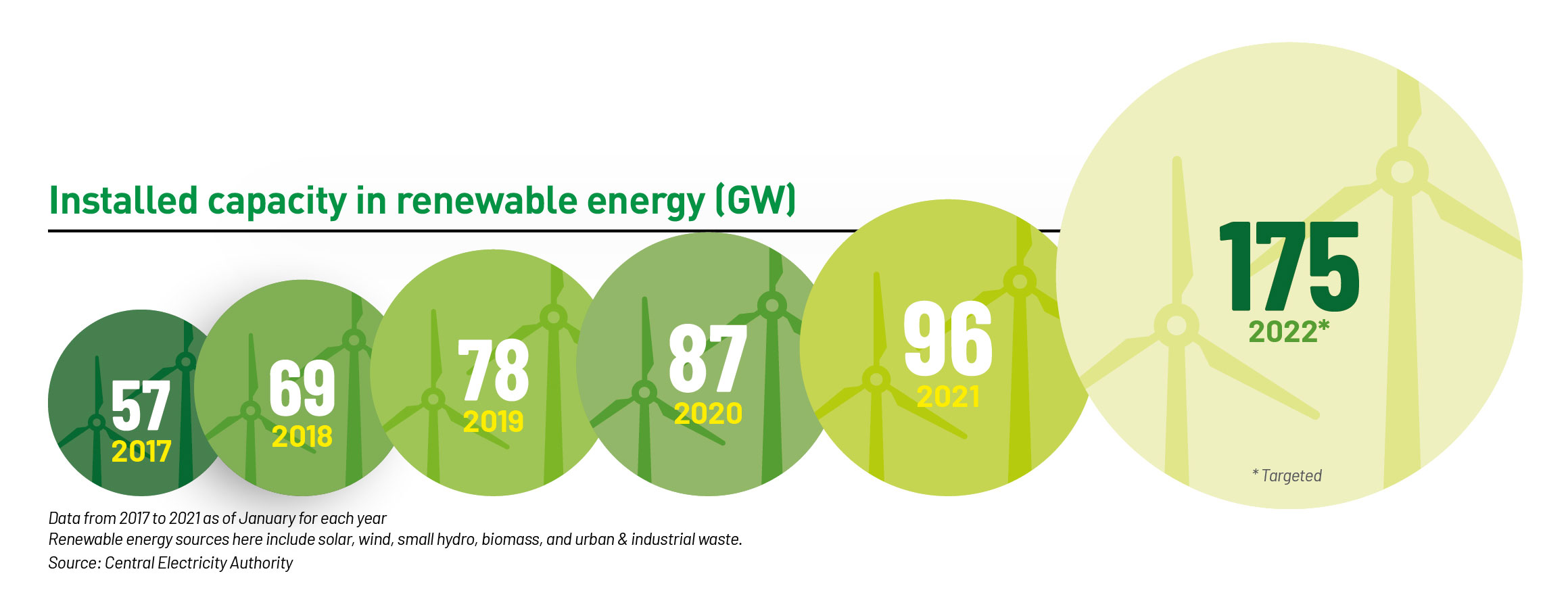

The Indian government has set a target to increase renewable energy capacity to 450 GW by 2030 - about five times the current renewable capacity. An intermediate target in this is 175 GW by 2022. On the basis of the incremental growth in the past five years, India is likely to miss this. The big push has to come from solar, whose share in renewable energy capacity has increased.

RENEWABLE SHIFT

According to the European Parliament, carbon neutrality can be achieved through a balance between emitting carbon and absorbing carbon through carbon sinks. To date, no artificial carbon sinks are able to remove carbon from the atmosphere on the necessary scale to fight global warming.

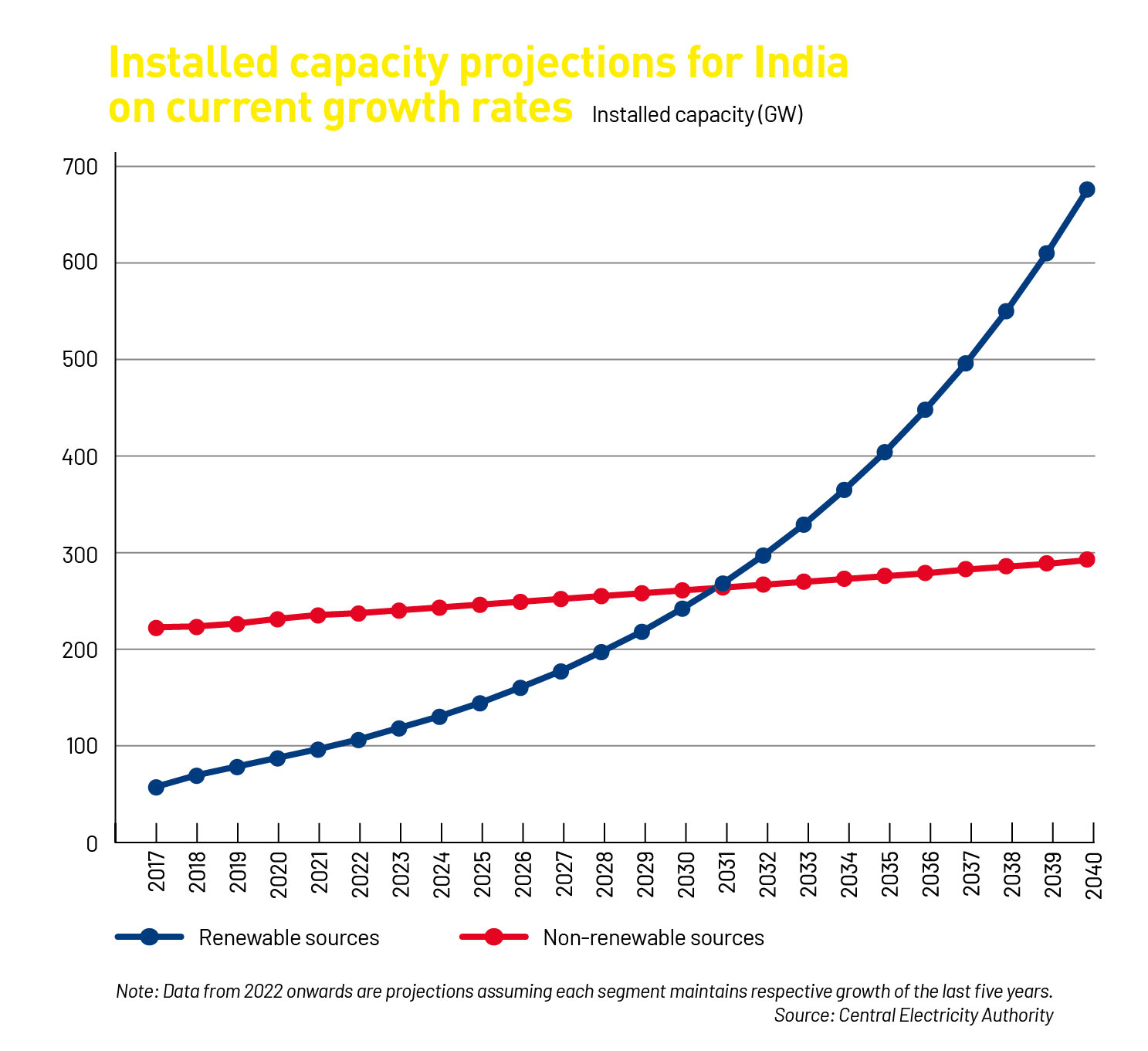

Another approach to net zero emissions is carbon offsetting: offset emissions in one sector by reducing them elsewhere. That's what sources of renewable energy do. As of 2021, renewable energy accounted for about one-fourth of India's total power capacity. But in the past five years, renewables have grown at a faster pace than non-renewables: compounded annual rate of 10% versus 1.1%. Assuming these rates hold, the two will be at par on capacity by 2031. And by 2040, renewables will be double of non-renewables.

According to the India Energy Outlook 2021 report, India is on course to reach net zero emissions only in the mid-2060s.

FINANCING CARBON NEUTRALITY

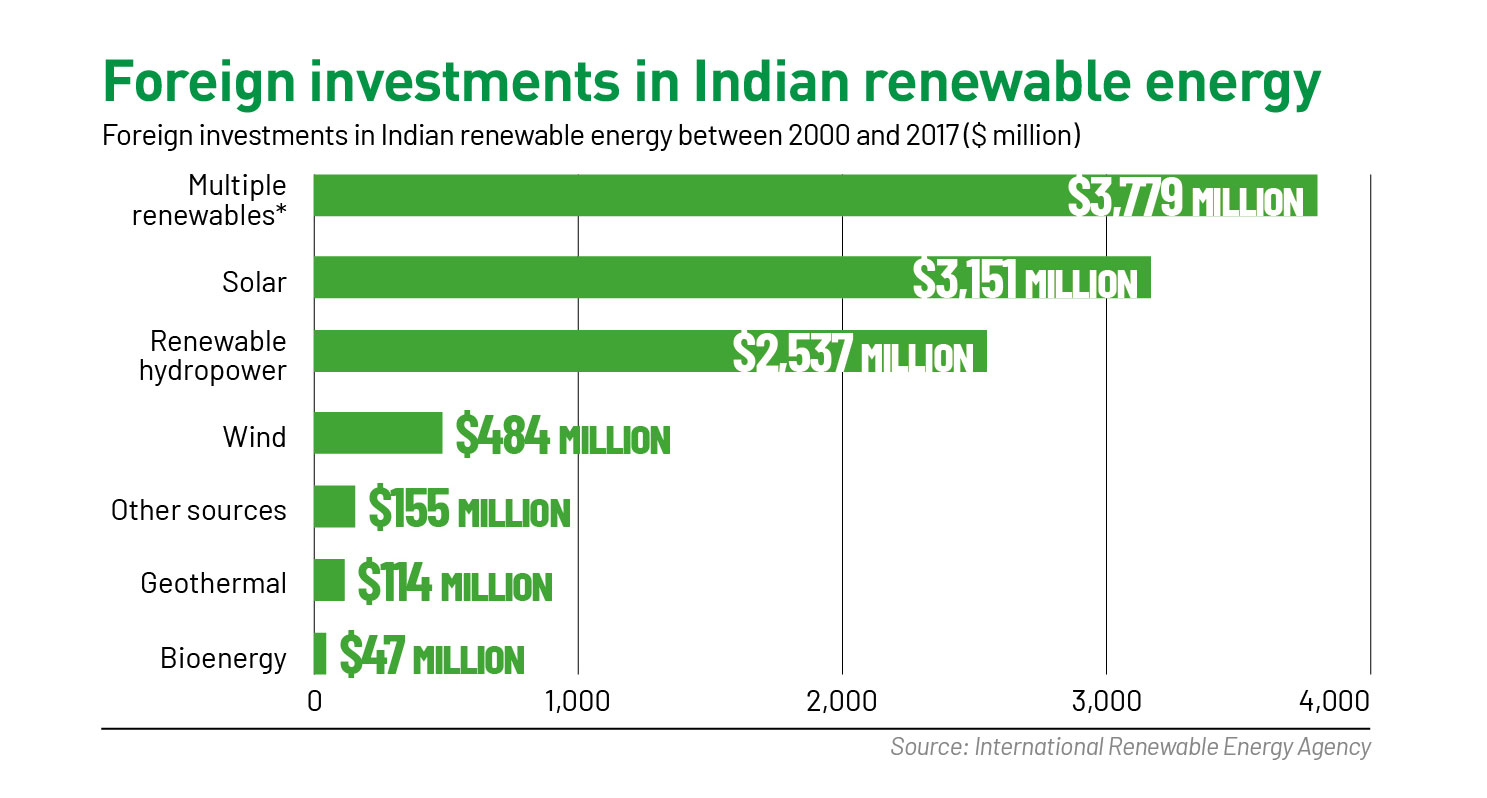

One challenge to scale up renewable capacity is funding. The scale at which India's energy production, storage and distribution capacity will need to grow to meet the carbon-neutral goal is one that will require foreign funding. Be it generation of renewable energy, technology adoption for electric vehicles or distribution network of batteries. Since 2000, India has received $10.3 billion in foreign funding for renewable sources. Only Brazil ($42 billion) has received more. About 31% has gone into solar.

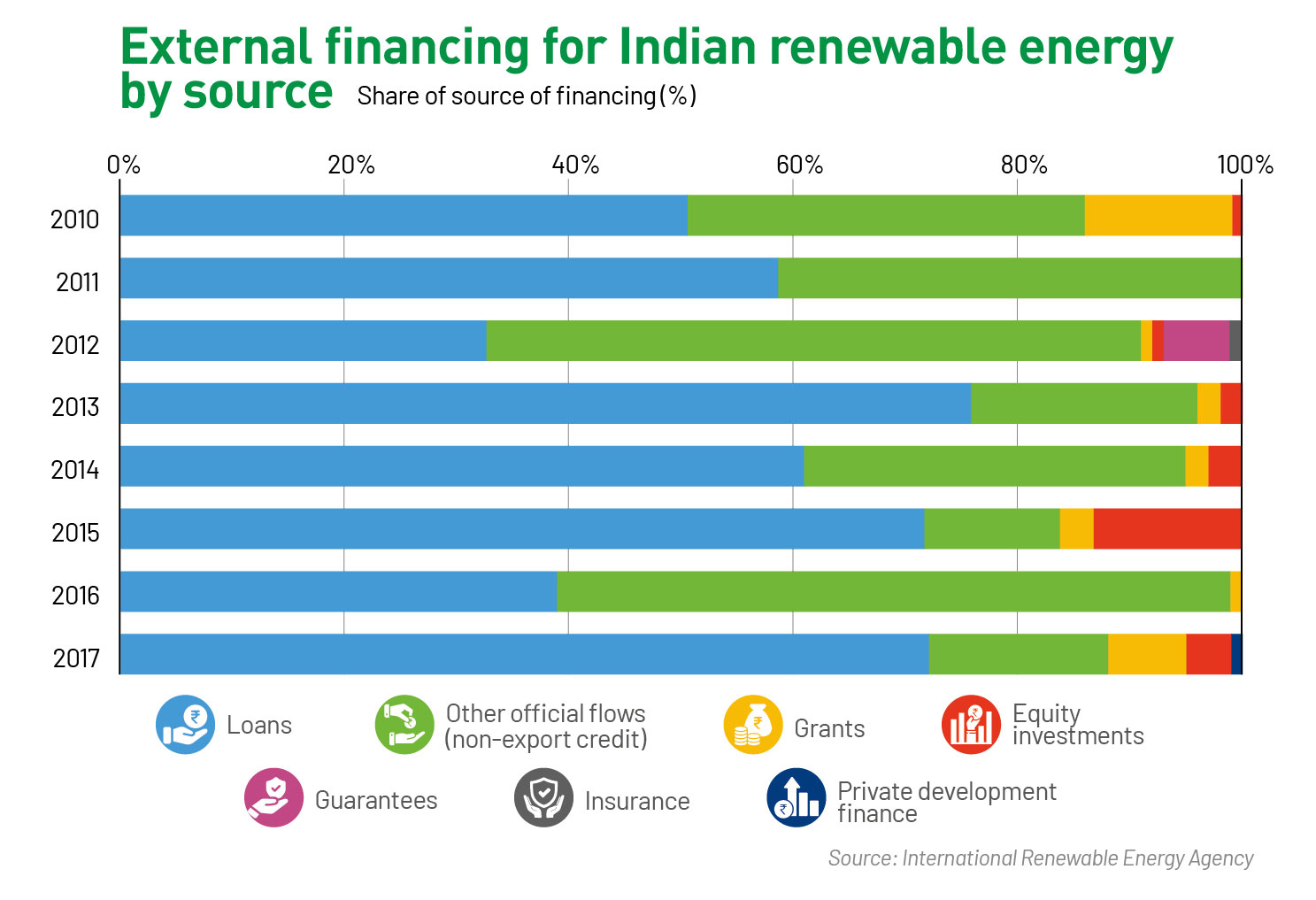

Currently India devotes nearly 3% of its GDP to energy investment, of which a large share goes to funding clean energy. External finance to India, though, has been inconsistent. Additionally, the dominant sources of funds, namely loans and other official flows (from partner nations), are not scalable. Scalable asset classes like equity investments and private development finance account for a small share in India's renewable energy basket. For example, for the U.S., the U.K. and Germany, equity comprises 80% of their renewable energy finances. To achieve carbon neutrality, besides capacity addition, India needs access to finance that is scalable and self-sustainable.

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH