Climate positive

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 04 issue 10 :: Nov 2025

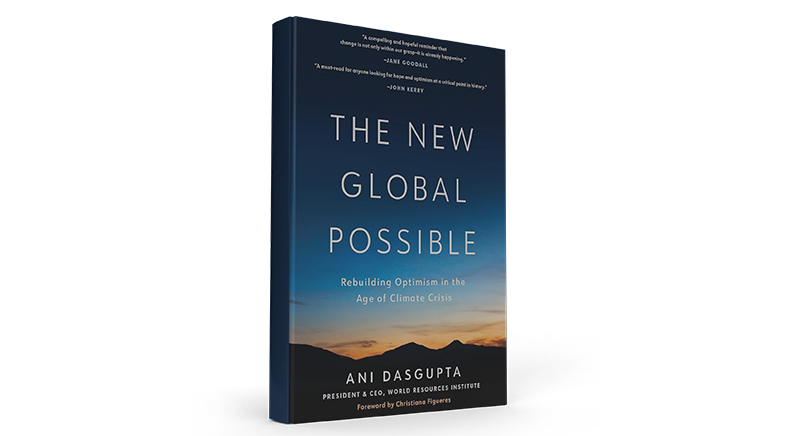

World Resources Institute CEO Ani Dasgupta on why he sees silver linings on the climate action front.

Ani Dasgupta is an architect by training, a captain of climate policy and finance by profession, and an optimist by outlook. President and Chief Executive Officer of the World Resources Institute (WRI), a Washington-based not-for-profit climate research organisation working to halt climate change and improve lives, Dasgupta channels that optimism in his book, The New Global Possible: Rebuilding Optimism in the Age of Climate Crisis. Even when discussing alarming developments and tipping points (see A grim climate reality) of Earth systems, he reckons that a better world is just round the corner. It isn't just a sunny disposition that makes him look at the brighter side of things. His personal and professional experiences in rebuilding lands wracked by disasters, and his interactions with champions of change across the world, have fashioned this outlook. Excerpts from a recent interaction with Shaastra:

What underlies your exuberantly optimistic outlook at a not-very-optimistic time in history?

When I became CEO of WRI in the middle of the (COVID-19) pandemic, the world was pretty disappointed at the pace of progress since the Conference of the Parties on Climate Change in Paris, 2015. Paris was a euphoric moment. I asked myself: as leader of WRI, what is my mission? I ended up talking to 100 experts, all luminaries in the area of climate action [to understand]. Their stories inspired me to write the book.

I learnt that we actually have achieved incredible things in the last 25 years. We just take them for granted. For example, 20 years ago, we didn't know how to measure carbon. Today, everyone talks in gigatons... We didn't know what net zero was, or the importance of 1.5°C temperature breach. There has been immense progress in science collectively, and I came away optimistic.

I'm not arguing that we should not be disappointed. I'm saying there are a lot of reasons to be optimistic. A very different future is possible, but it's not going to happen on its own.

Some developments since Paris are worth noting. Technological progress has happened at a pace we hadn't anticipated. Look at the growth in wind and solar power. Also, the cost of the technology has come down. Batteries cost a tenth of what they did three years ago, and the cost is expected to fall further. The market is producing technology faster than what we predicted.

Technology, however, isn't everything. We need to use that technology to the optimum. For instance, producing solar power needs to be accompanied by grid changes, acceptability, financing for connectivity.

Also, I argue that climate action can only work if evidence shows that those actions are also beneficial for the people [who are shifting to them]. The backlash against climate action in the Western world is largely because people are not convinced about what's in it for them.

You cite the golden moment in Paris. But we see cooperation crumbling: all it takes is for one President to walk out of the Paris deal.

This is a difficult moment [for multilateral cooperation]. It is reducing trust between countries; they need to work together not just for climate action. I was in New York recently for the Climate Week and, as predicted, President Donald Trump said [at the United Nations] that he does not believe in climate change and that the United States had decided to keep away from the Paris Agreement... But significantly, every other country that took the stage actually talked about its plans for climate action. It did not add up to the ambition everyone wants, and a lot more needs to be done, but no other country actually said no. Year after year, we have seen countries actually stepping up. Their public policy towards climate action hasn't changed because the future of their economic development... depends on the transition.

You write about African women who are farming macademia nuts. These are drops in an ocean. How can they withstand the tidal wave of powerful naysayers?

The story of these women shows economic transition, which we should focus on, and not just on climate change. Climate change is the outcome of a 200-year-old fuel-based economy. For us to change to an economy that is not based on hydrocarbons, these are the engines of change we need.

There is a fantastic group of women who work with 10,000 farmers to grow macadamia nuts on degraded land. There is a steady income from the processing and sale of nuts for the farmers, which incentivises them to care for the trees. These trees live for 50 years, and will sequester so much carbon. The economic transition should create climate action. Just this one story doesn't change everything, but the point I make is that the vehicles of transition should work for the people.

Talking of cooperation, we haven't been able to patch together a plastics treaty yet. Plastic isn't just an emissions problem; it's also a health issue.

It's actually sad that it has not been done so far. The reason is what I alluded to earlier: people do not want to switch from a high-fuel economy unless they see benefit in the new economy. Similarly, unless they see enough profits in switching over from plastic, they won't. They should have a lucrative alternative. And we need a strategy to bring in the incumbents of the old set-up into the fold.

Those who run the fuel economy are powerful and very vociferous in mobilising misinformation. Last year, the fossil fuel industry was a $7 trillion business. That is just one industry.

We have to understand the backlash and not just hope it will go away. We need to understand alternatives, and how to bring them along. I am very optimistic the treaty will be done.

How do you rate the trajectory of India's development and climate commitments?

People like me would always want India to be more ambitious. I want India to be a world leader, in this [field], and India is doing phenomenal things. For example, the big topic at the CoP Belém will be on how to finance transition to a green economy in middle-income countries. India's economy is large and growing, but countries also require inflow of private capital from outside. Most countries with similar economies, like Kenya and South Africa, are not getting the inflow that India is. We at WRI studied why. This is the answer: India made a very clear stand of what its climate ambition is. This ambition was put into policies, and financial instruments are in place to facilitate the energy transition.

"India has invested substantial public capital in energy. These [convey] how serious the Indian government is about the transition."

Most important, India has invested substantial public capital in the energy sector. These actions assure external parties about how serious the Indian government is about the transition. So, their risk perception is lowered.

India, however, has a big challenge. It is growing fast, and energy demand will rise accordingly... The renewable energy sector will find it difficult to catch up with rising demand. It will happen, but it will take time. So, while India is doing well on renewables, it will not be able to reduce emissions soon.

You write about cities as drivers of change. Given India's rate of urbanisation, cities seem drivers of more emissions.

Cities are absolutely drivers of more emissions. But it is also more easy for a movement to start in a city and grow bigger. I'll cite an example that isn't in the book. WRI did an exhibition in Mumbai with the municipal corporation on mapping heat. It showed a difference of several degrees in temperature across the city, highlighting the hotspots, especially slums. That exhibition resulted in civil society talking about heat mitigation; now, Mumbai is developing a heat reduction and resilience plan. And 40 cities are looking at climate as an integral part of their planning processes. This is what I mean by cities as drivers of change. The Indian government should be credited for focusing on cities. There is a new initiative on looking at cities as economic engines. WRI teams are also involved in this initiative. Cities are complex systems; they need expertise to be managed well.

What is your best-case scenario for 2100?

If we're able to live up to targets, and transition into a society and economy that is based on renewable energy, if we can shift to an agriculture system that doesn't destroy nature, yet produces food for over 10 billion people in the same agricultural space... that future is enormously positive for employment, for prosperity, for health. I do believe strongly, based on evidence across the world, that we will get there at some point. But would that be fast enough? Because if we do not, the cost of climate disaster, already $300 billion a year, will rise exponentially.

And your bleakest scenario?

There are 25 Earth systems that human societies depend upon, like coral reefs, polar ice and Amazon forests, each of which has a tipping point, beyond which the change is irreversible. If we do not take action in time, the bleakest scenario is that the tipping points will be breached. The Earth will continue: it has existed for billions of years, and is always changing. It will be a terrible scenario for the human species, however.

I am certain we will not get to that stage. During the pandemic, countries got together to pump in trillions of dollars to revive the global economy. Governments worked with businesses to create vaccines in months, which otherwise takes years. I think we've not been able to impress upon our leaders how catastrophic the [climate] future could be. Every day that we lose, the cost of inaction becomes that much more.

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH