Digital goes the easel

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 01 edition 03 :: Sep - Oct 2021

With emerging technologies embracing art, digital artists are tasting success - and raking it in.

Amrit Pal Singh has been a designer for nearly a decade now. Until recently, though, not many knew of him outside the world of design. But that was then.

Today, he is not just a hugely popular figure in the world of digital art but has also sold artworks worth about ₹2.9 crore so far. "Things changed so much in the last six months I don't even know where to begin," says Singh, 32.

To a large extent, behind his sudden success are emerging technologies such as blockchain and non-fungible tokens (NFT). NFTs were hardly a matter of public discourse even earlier this year. But in recent times the phenomenon has swept across the globe, as if to make up for the standstill in the real world.

"At the beginning of the year, I had no idea what those were," Singh recalls, referring to NFTs. He's richer for the knowledge.

Blockchain is a digital ledger that keeps a record of entries that are validated by all participants on the chain who agree to a set of rules or protocols. An NFT is simply an entry on a blockchain that is tied to a digital asset. In this case, the blockchain used to create NFTs is a decentralised, open-source platform called Etherium. When an asset changes hands, the token reflects that change, thus proving the ownership of that asset. This means people can now uniquely identify digital assets, or art, as in this case, and buy and sell it.

To simplify the concept of fungibility, consider the rupee. The value of a ₹2,000-note and that of four ₹500 notes is the same. So instead of using the former, you can use four ₹500 notes. Or if you exchange a set of ₹500 notes with another set, they still hold the same value. This means currency is fungible.

But a physical product, say a Raja Ravi Varma painting, has only one original and several copies. The copies can never replace the original in value. That is, the original object is non-fungible and unique. The value of art lies in the ability of the seller and buyer to establish provenance and, thereby, uniqueness. In the world of digital art, it was hard to verify the provenance of a piece since you couldn't distinguish between copies. But that changed with the NFT. Every piece of digital art that is an NFT can be uniquely identified.

CHANGING TRENDS

Growing up in Delhi, Singh had a passing interest in drawing. His parents, who run a business, allowed him to pursue a creative career and it became a serious pursuit after school. He joined the Vancouver Film School, Canada, in 2012, wanting to become a motion designer and work on animation. But when he came back to India, he found that most of the opportunities were in designing apps; thus began his career with start-ups and tech companies.

On the side, he started on 3-dimensional mock-ups that other designers could license from him and use in their own designs. By 2019, he was tired of the start-up ecosystem and wanted a break. Among these mock-ups were a set of toy faces that companies and designers could license and use. Singh called it the Toy Faces Library and launched it in June 2020 on Product Hunt, a product discovery site where users vote for items uploaded by its creators. The library became popular with nearly 1,400 upvotes and was the talk of the design and tech community. Adobe, which sells software to creators, funded Singh's Toy Faces project.

In February 2021, life took a new turn. Someone told him on Twitter about a "thing called NFT" and that Toy Faces would make great NFTs. Singh released toy faces that looked like artists Frida Kahlo and Vincent van Gogh first as NFTs later that month. "Suddenly I saw bids on those," he says.

A bidding war ensued and eventually the two pieces sold for a total of 7.6 ETH (ETH is short for Ether, the popular cryptocurrency built on top of the Ethereum blockchain). At today's prices, it roughly translates to ₹21 lakh. "I just had a great start and then I just went all out," he says. Since then, he has created and sold digital art worth 100 ETH (roughly ₹2.9 crore).

In the world of digital art, it was hard to verify the provenance of a piece since you couldn't tell fake from original. But that has changed with NFT.

Singh's growth is indicative of a wider shift: the melding of the worlds of technology and art, and thrusting art into the future. For the first time, digital artists have a way to bypass the traditional art scene centred on art galleries and cliques - not only for the artistic value of their creations but also for its growing importance as an investable asset for collectors.

"No one took me seriously seven years ago when I was talking about blockchain and art. Now everyone is waking up because there's money in it, and I love how it is throwing up some complex ethical dilemmas," says New York-based Raghava K.K., one of the earliest artists to work at the intersection of technology and art.

Raghava, however, argues that there are more speculators buying digital art today than people who appreciate art. "What we need is more believers. That way we can create a new asset class that will sustain art. That requires serious commitment," says the artist who has been commissioned to create several pieces of digital art across the world.

NFT FEVER

Driven by liquidity in the markets and fewer avenues for high-risk, high-reward bets, several investors have poured money into cryptocurrencies and NFTs. Deal-making on such platforms is moving at a feverish pace.

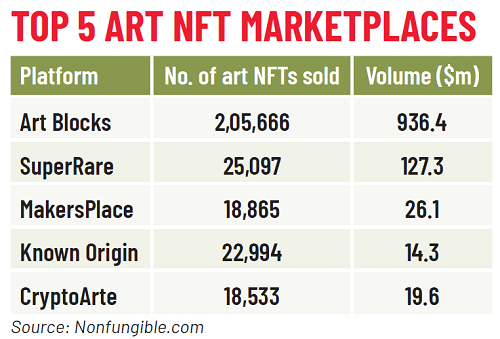

The process of creating an NFT is called minting and several platforms enable this for a fee. In the first half of this year alone, NFTs worth nearly $2.5 billion were sold on such platforms, up from $13.7 million in the first half of last year, according to data from Nonfungible.com, which tracks the NFT market. While some speculate that the market could slow down or even crash, it has been growing at an explosive pace until now.

An early attempt at creating and selling digital goods using the blockchain dates back to 2017, where a game built on Ethereum called CryptoKitties allowed users to buy, collect and breed virtual cats. The CryptoKitties frenzy died down but, in May 2020, Dapper Labs, the developers of CryptoKitties, launched a marketplace called NBA Top Shot where fans could buy video highlights of some of the greatest NBA plays. By May 2021, fans had bought clips worth over $700 million.

In February, Chris Torres, the creator of a 2011 viral meme called Nyan Cat, sold a unique re-mastered version of the video for nearly $600,000 on Foundation, an NFT platform. The original Nyan Cat meme was a YouTube video of a cartoon cat with a Pop-Tart body oozing a rainbow as it flew through space with a Japanese pop song in the background. In March, Twitter co-founder Jack Dorsey sold the NFT of his first-ever Tweet for $2.9 million. Edward Snowden's NFT - an image of his face made from the pages of a U.S. court decision on his mass surveillance exposure - was sold for $5.4 million in April.

Bollywood actors Amitabh Bachchan and Sunny Leone are also launching their own NFT collections. Bachchan's collection will include his father Harivansh Rai Bachchan's poem Madhushala and signed film posters. Leone will share a set of collectibles, including curated art and costume designs, on her site. Indian cryptocurrency exchange WazirX launched an NFT marketplace in June and has sold over 1,000 NFTs so far.

"Collectibles that have a piece of history or meaning for a generation of people who grew up online fetch a high price," says Nitin Sharma, an early-stage investor in crypto start-ups. He adds that some of the emotions and values that buyers associate with digital art today are fame, cuteness, sex and even dankness (dank memes refer to unique or odd memes).

Sharma stresses that there is a "gold rush" for NFTs. "And that's because there's too much liquidity in the market; people have made millions in crypto and some amount of speculation," says Sharma, who runs a fund called Antler in India and is seeking to invest in start-ups that make "the picks and shovels" in this gold rush.

The big breakthrough in the field came when auction house Christie's sold an NFT called Everydays: The First 5000 Days by artist Michael Winkelmann, who goes by the alias Beeple, for $69 million. It was later revealed that the buyer was a Tamil Nadu-born crypto entrepreneur called Vignesh Sundaresan, who goes by the name Metakovan in the virtual world. The auction was prime-time news on nearly every top television channel and newspaper. The internet was abuzz with the story for days.

CHANGING DEMOGRAPHIC

The changing demographic of prospective art buyers and people who want to experience art is also promoting innovation. "Galleries have no choice but to evolve. There's a whole demographic that experiences art in digital forms and they're now starting to buy," says Aparajita Jain, co-director of Nature Morte, a leading contemporary art gallery in New Delhi. Jain recently launched Terrain.art, an NFT platform that has curated the works of several digital artists.

That new demographic is already spending a considerable amount of time in the metaverse - a virtual shared space - through video games or on video conferences. "For my 16-year-old son or my daughter, video games and platforms such as Instagram are where a lot of their time is spent. They're already in the metaverse," Jain adds.

Bollywood actors Amitabh Bachchan and Sunny Leone are also launching their own NFT collections. Bachchan's NFT collection will include his father Harivansh Rai Bachchan's poem Madhushala and signed film posters.

Most NFT collectors are crypto enthusiasts or even crypto millionaires who are fascinated by art. They also look at an NFT as an investment. A typical collector would invest in several artists and hope that these artists earn fame in the future, making their own collections more valuable. They also invest in collectibles such as the Nyan Cat or projects that sell a limited number of collectibles such as CryptoPunks and the Bored Ape Yacht Club, Dorsey's first Tweet or computer scientist Tim Berners-Lee's source code for the World Wide Web.

THE METAVERSE

Harshit Agrawal is one of India's earliest artists to co-create art with artificial intelligence. He recently curated an art show titled Intertwined Intelligences for Terrain.art. The idea took shape when he tried to create what a digitally native future would look like. "We've already started spending much of our time in digital worlds. More so during the pandemic. Given that, I wanted to try and show how humans can co-imagine a future with artificial intelligence which will be a big part of our digital worlds," says Agrawal, whose solo exhibition at Kolkata gallery Emami Art, which got under way in mid-September, explores some of these themes.

With digital art, the possibilities for artists to engage with the future have also grown, giving those from the global South a bigger platform of expression. "Unlike in the West, the Eastern world does not look at anything as binary. The binary view, which is big in academic circles, is crumbling because they are based on absolute truths in a conceptual world. The human experience of art is detached from all that," Raghava says.

"In the East, we live art," he adds. "We experience it in a truly democratic way. It's a conceptual and radical shift. NFTs are saying that we want artists to rise to that occasion. This is the sentiment. Not the gold rush where people are hedging from one currency to another. Where is the art in that?"

That his work was finally considered as art and not a product mattered to Singh. "For the majority of my career, digital art was not seen as art. It was always considered more commercial even though it is as intense as, say, painting on a canvas," says Singh, who recently created a series of NFTs called Martian Bunkers X Bored Elon in which he captures an imaginary future on Mars.

THE FUTURE OF ART

The gallery model is also changing. In the NFT community, artists work on their own promotions, marketing and building an audience. In the traditional world, the gallery does most of that work for artists in exchange for a hefty fee. In NFTs, the majority of the proceeds from a sale will go to the artist. The marketplaces that facilitate this trade typically charge a fee between 2.5% and 15% of the value of the art piece. Also, unlike in the traditional art world, in the world of NFTs, artists can also earn from secondary sales. That is, every time the artwork changes hands, and there's an appreciation in its price, artists stand to benefit. In the non-digital world, proceeds from secondary sales often go to collectors or galleries. "With NFT, on every sale you get 10%," says Singh.

What Metakovan plans to do with the artwork he has purchased offers a glimpse of the future. He imagines setting up an art museum in the metaverse where users can see some of the digital world's most important artworks, including Beeple's art.

The gallery model is also changing. In the NFT community, artists work on their own promotions, marketing and building an audience.

His company, Metapurse, plans to hire some of the world's best architects and build a virtual world of art. "We intend to create a monument that this particular piece [Beeple's work] deserves, which can only exist in the metaverse," Metakovan told The Art Newspaper in March.

Organisations such as Metapurse themselves could be run on the blockchain. This new type of a body is called a decentralised autonomous organisation where the company rules and governance are burned onto smart contracts on the blockchain without a central authority controlling it.

"How we deal with technologies like blockchain and artificial intelligence will be the most defining aspects of how humanity moves forward. The idea of post-human and decentralised ownership is very much here and artists will engage more and more with it," says Agrawal.

The current sentiment throws up stimulating dilemmas for artists. Raghava holds that just because it is easy to commodify art now, it doesn't mean that it must be sold. "If everything is digitisable and commodifiable, should everything be put up for sale?" he wonders.

The true job of an artist, according to Raghava, is to make art more inclusive, not exclusive; hopeful, not hopeless; healing, not anxiety-inducing; future-facing, not backward-looking. It must be relevant and not academic and a way of life more than a commodity, he holds. Even as it throws up ethical dilemmas for artists, the world of digital art and NFTs make all this possible.

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH