B(l)ack to the basics

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 03 issue 06 :: Jul 2024

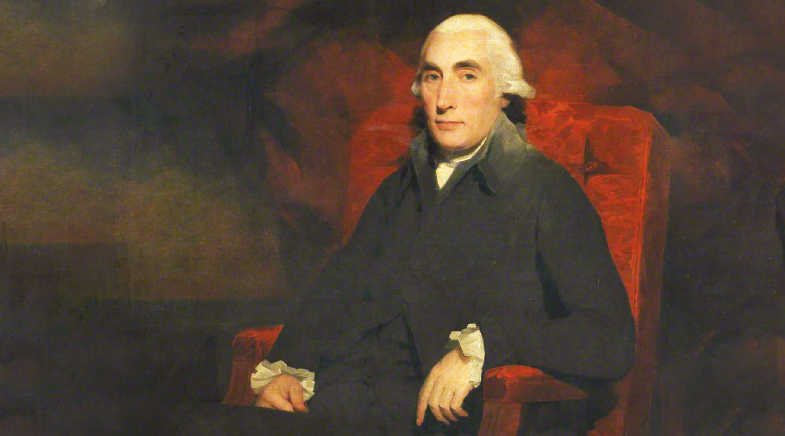

Scottish chemist and physician Joseph Black did fundamental work on gases and heat.

In 1752, when Joseph Black had to pick a dissertation topic for his medical studies at The University of Edinburgh, he was in a fix. He wanted to study the medicinal properties of limewater derived from quicklime (calcium oxide), which his adviser Charles Alston thought could treat kidney stones. But Alston was in the midst of a fiery battle with another scientist, Robert Whytt. The two disagreed about many things, including what the right source for limewater was, and what made quicklime caustic.

To avoid getting caught in the crossfire, the amiable Black decided to study a compound called magnesia alba (magnesium carbonate) instead. When heated, it produced magnesia usta (magnesium oxide), and gave off a vapour that he called “fixed air”. Black noticed that the vapour was heavier than air, could extinguish candle flames, and was deadly to birds that breathed it in. In one experiment (bit.ly/limewater-church), he apparently let limewater drip onto rags kept in the air duct of a church ceiling; the parishioners’ exhaled breath converted the limewater to chalky calcium carbonate, proving that the vapour was a respiratory gas. His experiments with the vapour – which turned out to be carbon dioxide – opened the doors for the discovery of other gases like hydrogen, nitrogen and oxygen in the next few years.

PAPER CHASE

Black published few papers about his research, despite having made several discoveries. James Watt even wrote to him once, urging him to publish his work on latent heat – which others had also begun studying – stating: “I cannot bear to see so many people adorning themselves with your feathers.” But Black preferred to share his discoveries with students during his lectures.

In 1756, Black became a lecturer at the University of Glasgow. By then, his attention had turned to heat. He realised that when ice becomes water or when steam condenses, the temperature remains the same, even though a large amount of heat is absorbed or released; he called this latent heat (bit.ly/black-heat).

His experiments with carbon dioxide opened the doors for the discovery of other gases like hydrogen, nitrogen and oxygen.

That same year, the university hired a young James Watt as a technician. Impressed by Watt’s “uncommon talents for mechanical knowledge and practice”, Black befriended him and discussed his theories on latent heat with him. A few years later, Watt got the chance to repair a Newcomen engine, the first practical steam engine, which was highly inefficient. It had only one cylinder in which steam was cyclically created and condensed. Watt noticed that a lot of water was needed to condense the steam, which he deduced was due to the large amount of latent heat trapped in the steam. In addition, a lot of energy was wasted in reheating the cylinder, which cooled as the steam condensed. Watt then designed a separate condenser for the steam to avoid heating or cooling the original cylinder, making the engine much more efficient. His new design took off, fuelling the first industrial revolution. Black and Watt would remain in touch for many years (bit.ly/black-watt-letters).

MONEY MATTERS

When it came to finances, Black was a man of contradictions. On the one hand, he would carefully weigh the guinea coins his students paid to him to attend his lectures, to ensure he wasn’t being cheated. On the other hand, he was generous with his money – he loaned £1,000 to Watt (go.nature.com/45rwauB) for developing the steam engine, treated poor patients for free, and left behind a generous sum of £20,000 to his heirs.

In later years, Black became a much-revered lecturer, credited with popularising chemistry among youngsters. Hundreds of students from within the U.K. and abroad flocked to listen to his clear explanations and watch his experimental demos. Black also took on several administrative responsibilities, including managing the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, and was appointed physician to King George III. Unmarried, he lived a rich social life, hobnobbing with eminent philosophers and economists, and died at home on December 6, 1799.

Ranjini Raghunath is a Bengaluru-based science writer and editor.

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH