Blinded by science

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 03 issue 04 :: May 2024

How science became disconnected from human experience.

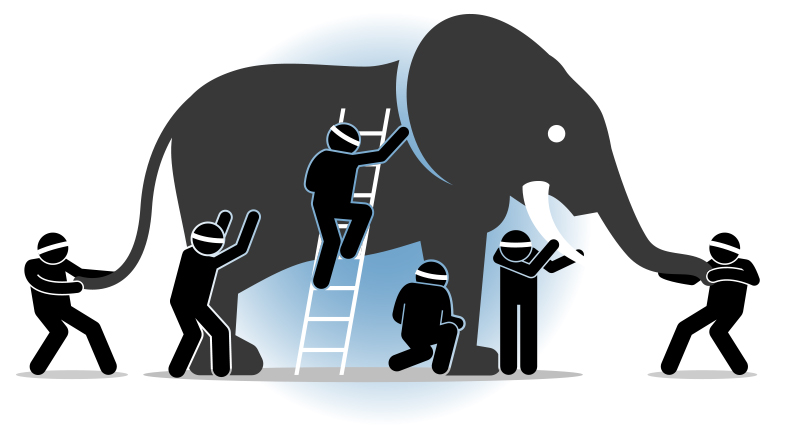

This is an unusual book. It opens with a declamation from the authors – astrophysicist Adam Frank, theoretical physicist Marcelo Gleiser, and philosopher Evan Thompson – that "we need nothing less than a new kind of scientific worldview". A central theme throughout the book is how science, as practised by professional scientists, has become progressively disconnected from its core purpose of enriching and amplifying the human experience of the beauty of the universe. The title of the book – The Blind Spot – derives from a memorable and powerful metaphor: "At the heart of science lies something we do not see that makes science possible, just as the blind spot lies at the heart of our visual field and makes seeing possible. In the visual blind spot sits the optic nerve; in the scientific blind spot sits direct experience..."

Where the book truly shines is in highlighting subtle incongruities in the standard 'objective' version of science. A great example here is the discussion of French philosopher Henri Bergson's point that "clocks don't measure time; we do." It highlights the fact that scientific measurements of time are based on periodic motions – whether of a pendulum, springs or atoms – that are distinct from the experience of duration or any truly temporal measure that has not been spatialised. As I read these words, I was struck by an intense memory of the confusion of my younger self, while reading the explanation of relativistic time dilation on a spaceship, shown through longer travel paths of moving light clocks for an external observer on Earth. That the ship clock runs slower for the observer was easy to grasp, but that relative experiential time or ageing will slow down for the cosmonauts was not. While this gap is seemingly resolved by thinking of cellular processes as mini-molecular clocks that also slow down, based on experimental studies, Bergson's debate with Einstein on the meaning of time clearly enriches rather than detracts from science. However, this example also brings out the challenge of experience-centric thinking in science. Should Einstein's gedankenexperiments (thought experiments), such as riding a light beam, be considered experiential on a different scale? What does experience really mean here and would a narrow view of it not be equally damaging?

Consider an early discussion in the book on how the general human experience of hot and cold led to the genesis of relatable temperature scales with zero linked to freezing of water, which have since yielded the pride of place to thermodynamic theoretical concepts such as absolute zero and the Kelvin scale, dissociated from any human experiences. The book criticises this, saying that "the Blind Spot arrives when we think that thermodynamic temperature is more fundamental than the bodily experience of hot and cold". I am certain that at least some people like me will find this line of argument fallacious. I personally wondered whether the authors are aware that human hot and cold receptors are peculiar in that while they fire oppositely across the typical range of temperatures, at extremes they start firing similarly. This explains why hot water near 50°C can feel icy to touch, and why there are instances of extremely cold water inducing burning sensations. Human experience of hot and cold is thus messy, as most biological things are.

Science, as practised by scientists, has become disconnected from its purpose of enriching the human experience of the beauty of the universe, reckon the authors.

While the authors take care to differentiate their 'grounded' view of science from anti-science or pseudoscience, it does seem that their sense of the problem is far better developed than that of any specific solution. I see this book as essential reading for those interested in the philosophy of science; it is best seen as the diagnosis of a complex lifestyle disease, without any real prescription beyond eschewing unhealthy habits. That is perhaps for the best since this book may well go on to become a classic at a time when popular opinion is shifting away from science. Over-prescriptiveness would risk creating additional blind spots, rather than removing the one.

Dr Anurag Agrawal is Dean, Biosciences and Health Research, Trivedi School of Biosciences, Ashoka University.

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH