It's the science, silly!

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 05 issue 01 :: Jan 2026

Curiosity‑driven scientific inquiry, seemingly without a 'use', isn't a luxury. It forms the foundation of innovation.

The Indian Institute of Science and the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research are very different kinds of institutions; yet, they are both extraordinary in what they have done for India and, indeed, the world. They are iconic among the many Indian institutions where fundamental research has thrived without being asked the question: "Of what use is this?" The list of such research institutions is long: the Indian Statistical Institute, The Institute of Mathematical Sciences, the Raman Research Institute, the S.N. Bose National Centre for Basic Sciences, the Indian Institute of Astrophysics... These are treasures that protect us against an uncertain future.

When India's investment space and atomic energy programmes were started, there were strong headwinds in India and abroad. The argument went that these were luxuries, and that Indian policymaking should focus on primary education, agriculture, and health, and only later worry about these areas. However, the satellites launched by India's space programmes have been transformative for many sectors of the economy and for education. The atomic energy programme has transformed access to radiology resources for cancer treatment. Access to nuclear energy will grow steadily and is a long-term investment. These areas of investment have a 'pay-off' path, directly or indirectly. A taxpayer, and even a tight-fisted finance mandarin, can be persuaded about their eventual high value. This is even more true today than it was in 1947.

SHOOTING FOR THE STARS

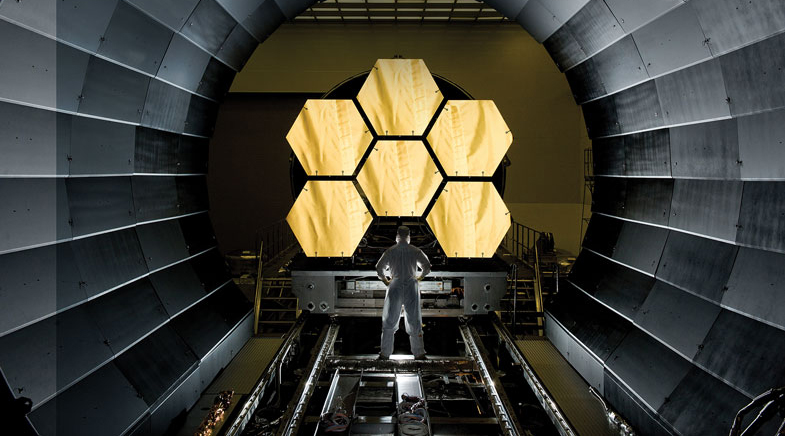

If fundamental research in space and atomic energy programmes can be defended as having near-future use and therefore being worthy of taxpayer support, what about astronomy and astrophysics? Humanity's never-ending quest to understand the universe seems to get countries to sign very big cheques for astronomy and astrophysics research. The James Webb Space Telescope cost about $10 billion; the Hubble Space Telescope cost about $12 billion over its life‑cycle; and the development and launch of the Chandra X-ray Observatory cost about $2 billion. Like the United States, India and several other countries have invested in various terrestrial telescopes and observatories. These include the Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT) coming up in Hawaii; the Square Kilometre Array in South Africa and Australia; and the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO), whose Indian component is coming up in Maharashtra. These are not small investments, but were made with enthusiasm. Astronomy and astrophysics research processes enormous amounts of data and image processing. Setting up these telescopes requires deep engineering capabilities. Therefore, it could be argued that there are many collateral benefits from these investments. The quest itself is a magnificent exploration of our universe, without promises of economic rewards; it is this quest that drives support for research in astronomy.

Research in mathematics and theoretical physics is far less expensive than in experimental physics. Even so, it is a struggle for researchers in these areas to secure funds for travel and computational support – although they have no problem getting a generous supply of paper, pencils and chalkboard! For this very modest investment, their contribution to the economy and society has often been transformative. Linear algebra, vector spaces, and statistics drive much of today's world.

'SILLY' SCIENCE ISN'T SILLY

In such a situation, where some areas of basic science receive government support and others don't, how do the life sciences fare? The Salmon Cannon and the Levitating Frog: And Other Serious Discoveries of Silly Science, by biologist and science communicator Carly Anne York, is a narrative that defends curiosity‑driven research by demonstrating how seemingly frivolous experiments have catalysed major scientific and technological advances. York structures the book around a series of case studies, each exploring research that appears "silly" on the surface but reveals deeper scientific principles and practical applications.

Many of these quirky examples are well illustrated. From the study of how shrimps walk on treadmills, to how fruit flies deal with day-night cycles, and why there are protrusions on the fins of whales... such research studies are viewed quizzically by the lay public and by politicians alike. Are we not wasting taxpayers' money on weird and "useless" research? York illustrates, in an American context, many examples of politicians of all stripes fuming at such wasted money. Some of the criticism is no doubt valid. While the sanctioning of research projects is done after a complex review process, there are many examples of questionable funding and, perhaps more, of good proposals being rejected. While some of this is par for the course in review mechanisms, the egregious examples are not the studies about the shrimp or the fruit fly, which catch the politicians' eye and public ire. York shows that they are actually quite worthy of support. Several projects are sanctioned because they work on pressing problems — some cancers, Alzheimer's, ageing, and so on. Not all of them may merit the support they often get. Just as people moan about the shrimp-on-a-treadmill project, many fund big projects just because they are in an 'important' area. There is a lack of understanding in both situations.

Life sciences research is often a target of misplaced ire because scientists have not communicated well the relatedness of all life on Earth through evolution. This quote from Darwin may be overused, but it is underappreciated:"There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed into a few forms or into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved."

What "having been originally breathed into a few forms or into one" means is that all life on this planet has a common origin, a conclusion that is now well established by evidence and no longer just a theory. And what "a common origin" means is that all life has a shared chemistry. It is because of these two facts that we can, astoundingly, learn about the molecules that cause colorectal cancer from studying how a fly's wing is made. The molecular kit that is used to make parts of a worm, fish or fly — organisms that basic researchers study — is also used to make us. This is similar to saying that nuts and bolts and rivets can be used to make a small club airplane or a large jet aircraft. The rules for where, when, and how the tools are deployed vary, resulting in very different products.

Science's greatest breakthroughs often begin with simple wonder; society benefits when curiosity is allowed to run wild.

Fascinatingly, it is not just that the molecular kit is conserved across species. Nerve and muscle cells that are used to think and to move have many similarities from worms to humans. And it is not the molecules and cells. Complex groups of cells, such as brain circuits and blood, can have conserved similarities. Finally, if all this were not enough, many ways by which animal development and behaviour come about have underlying similarities across species, including humans. The swimming pattern of a leech seems a useless area of research. Aside from understanding the beauty underlying this elegant movement, the nerve circuits that control it have a lot to say about how our spinal neurons control movement. How a fly's day-night cycle — the circadian rhythm — works turns out to have an almost identical mechanism to ours; work that resulted in a Nobel Prize.

THE CASE FOR CURIOSITY

The book's central thesis is that science requires "space for play and creativity" and that curiosity‑driven inquiry, far from being a luxury, forms the foundation of innovation. York argues this point through storytelling, showing how questions like "How fast can a mantis shrimp punch?" or "Why do wombats produce cube‑shaped scat?" have led to breakthroughs in fields ranging from materials science to medical diagnostics. The book is a witty, well‑researched celebration of curiosity‑driven science. York demonstrates that seemingly absurd questions can lead to profound discoveries. Her purpose is to make a compelling case for protecting and funding basic research. Her engaging storytelling and clear prose make complex science accessible, while her advocacy is both passionate and evidence‑based. There are many examples to show that science's greatest breakthroughs often begin with simple wonder, and that society benefits when we allow curiosity to run wild. A fun read at one level for kids and adults, and at another, a book that raises very serious questions on how basic science can be better supported.

Dr K. VijayRaghavan, former Principal Scientific Adviser to the Government of India, is emeritus professor at the National Centre for Biological Sciences, Tata Institute of Fundamental Research.

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH