Health on your plate

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 03 issue 09 :: Oct 2024

Science is trying to figure out the individual variations in how people respond to specific categories of food.

Human beings have known for long that diet plays a major role in health and disease. However, the specific nature of this role was never clear in most cases. Does fat contribute to heart disease? Is milk good for health? Does eating meat contribute to colon cancer? What is the best diet for a diabetic? And so on.

Conventional advice on diets boiled down to common sense. "Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants." These three opening sentences in Michael Pollan's book In Defense of Food still ring true as sensible advice. Ancient cultures stressed the importance of moderation combined with frequent fasting to maintain good health. However, in spite of such seemingly good advice and significant recent knowledge about nutrition, the overall advice still remains simple and not useful in many instances. No refined carbohydrates, no saturated fat, no alcohol, eat early at night... However, the rising number of lifestyle diseases worldwide makes it seem that such counsel does not work well even if followed in a larger sense.

Early research shows the promise of personalised nutritional science in preventing or reversing serious disease.

The confusion is most pronounced when someone has a health problem to begin with, like excessive weight or diabetes. There are many different diets that promise weight loss, and many of them indeed work in the short term. However, the effects of many of them seem to be temporary, as several people gain back the lost weight after a period. Depending on which study you cite, 80-95% of dieters in the West gain back lost weight in two to five years. It isn't clear whether some of those diets – the ketogenic diet, for example – are healthy in the long term. It is no surprise, then, that the layperson is confused about what to follow.

Over the past decade, research has provided insights into why people gain back lost weight. The body is quite dynamic, and it compensates for the calorie restriction by changing the metabolism. For example, hormone levels shift, getting many people to eat more than what they were eating during the dieting regimen. However, these were preliminary observations. There is yet no deep understanding of weight loss and weight gain in relation to what we eat. It is not possible to conduct controlled studies on human beings for a long duration. Beginning in the late 1980s, two famous studies over 20 years on rhesus monkeys – one by the National Institute on Aging, in the U.S., and the other by the University of Wisconsin – gave different results on the benefits of calorie restriction.

Our Cover Story looks at this problem from a different angle: how science is trying to figure out the individual variations in how people respond to specific categories of food. Such attempts are part of what is increasingly called precision nutrition. We do not use that phrase in the story, partly because we think that nutrition is far from being a precision science. Manupriya and Richa Agrawal report on some early attempts to understand individual variations in how people react to different diets. Although conclusive evidence may take a decade or longer to arrive, early research shows the extraordinary promise of the field in preventing or reversing serious disease.

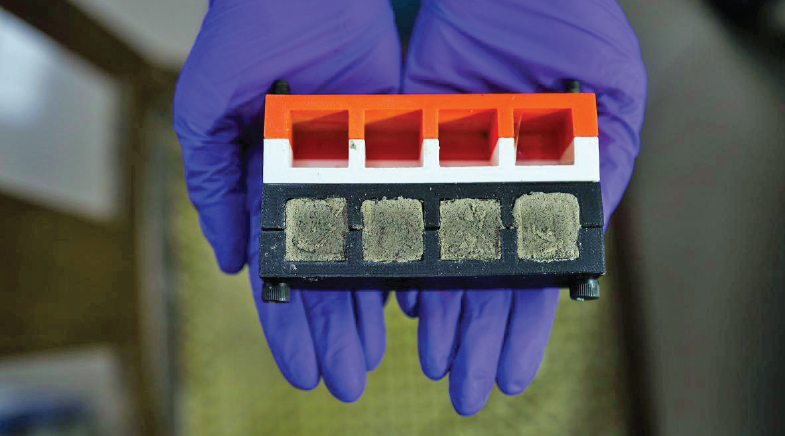

The story focuses on three key aspects of current research: the rising use of the digital twin, the manner in which genes affect the way food impacts health, and how the microbiome influences the impact of what we eat. All three have become major areas of research in nutrition. The digital twin has been used in manufacturing for two decades, but its use in healthcare has been increasing steadily in recent years. Early evidence points to its utility in tweaking diets to suit individual needs. Similarly, there is evidence that different people respond differently to specific diets based on the genes that they have, thereby providing another powerful way to modulate the diets of people who are at high risk for metabolic diseases. Similar findings hold true for the microbiome as well. Combining all these trends and extrapolating into the future, it is not hard to see that scientists are beginning to understand the complex connections between nutrition and serious disease. And thereby learning to control many serious diseases beyond managing the symptoms.

See also:

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH