Lost in translation

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 03 issue 05 :: Jun 2024

India's R&D spending is modest, which is why it must get more bang for its buck. Here's how that can be done.

About 60% of R&D spending in India, or about $14 billion, is on taxpayer-funded public institutions. That's unlikely to go up, given the government's other compulsions; so, research funding focus is prioritised towards critical public health problems: infectious diseases, malnutrition, and so on. Prioritisation, however, does not guarantee substantive results. One area that needs attention is the "translation" of research findings from the laboratory to products and services for the community. A drug that works on mice must be proven to work in clinical trials on humans before it can be approved. A vaccine that is stable at –20°C must prove effective when temperatures soar in summer.

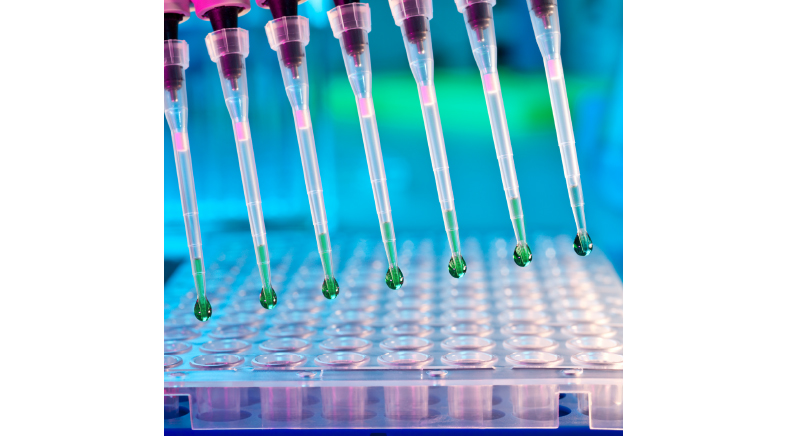

Translational work happens at the intersection of two cultures: the culture of invention (which scientists are steeped in) and the culture of innovation (as in biotech companies focused on getting an invention to the market). Many inventions die in the 'valley of death' between the lab and the marketplace.

How does India fare in translating scientists' work into market products? Consider the Council of Scientific & Industrial Research, created specifically to commercialise research. One of its institutes, the Central Drug Research Institute (CDRI), founded in 1951, has just three marketed drugs to its credit: an antimalarial, a contraceptive, and an Ayurvedic formulation that claims to improve memory. This is an unflattering record. But CDRI is not unique. Most academic institutes struggle to translate the promise of research into public goods.

Translational failure is not unique to India, but it is especially problematic for a country that needs urgent solutions and works with limited resources. Funding for science needs taxpayers' support and political will, both of which will wane in the absence of tangible examples of research application to real-world problems.

The translational gap is bridgeable. Many biopharmaceutical companies conduct laboratory research similar to what's done in academia, but the dynamics are different. With investors breathing down their necks, they are motivated by profits, and are driven by the mantra: 'Fail early, fail fast'. The opportunity cost of pursuing bad ideas or delaying critical experiments is high; so, corporate leaders drive productivity and speed in their search for marketable drugs. This could be a template for efficient translational work for academic scientists, too.

Academic scientists typically work in small groups with deep expertise in one problem area. Excessive focus on one area of biology without the broad exposure to other topics needed to develop the invention limits their ability to 'translate'. They are also cramped by lack of access to step-up funding and to research capabilities needed for the definitive animal model studies to decide if the invention is worth pursuing. Researchers therefore go on cruise mode, exploring research bylanes with incremental funding, rather than doing the defining experiments that will establish the applicability of their research findings in the real world. The invention festers and fizzles out, losing patent protection (if it was secured at all).

A market-focused model for lab research, similar to the biopharma industry's, will help academic scientists bridge the translation gap.

The current system of incentives in academic science does not encourage translational work. Scientists are rewarded for publishing papers, not for pushing their inventions through to the market. And there are no allowances for late-stage failure of ideas. This, too, disincentivises scientists. Effectively, academic science is shielded from the marketplace. That's a good thing in basic science, where independent thinking needs to be nurtured, but not while developing a product, where scrutiny by objective experts is critical.

Translational work is collaborative. The rapid development of multiple COVID-19 vaccines shows what is possible when academic science works alongside commercial entities. India's space mission success was catalysed by scientists and technologists working together. Academic institutions are unused to this style of working, but one solution is to custom-design an organisation that can take on translational work in collaboration with academic scientists. Such an organisation can cherry-pick promising ideas and fund them. Based on that, further investments can be made – or ideas abandoned: this is the 'Kill early, kiss fast' approach.

India's modest R&D spending limits the pool of ideas generated by its scientists. It would be a shame if even this limited pool goes to waste because things get lost in translation and a life-saving innovation does not reach the market.

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH