The future of cities

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 03 issue 11 :: Dec 2024 - Jan 2025

Cities will determine the Earth's future. Therefore, humans need to create the right kind of cities. Here's what that means.

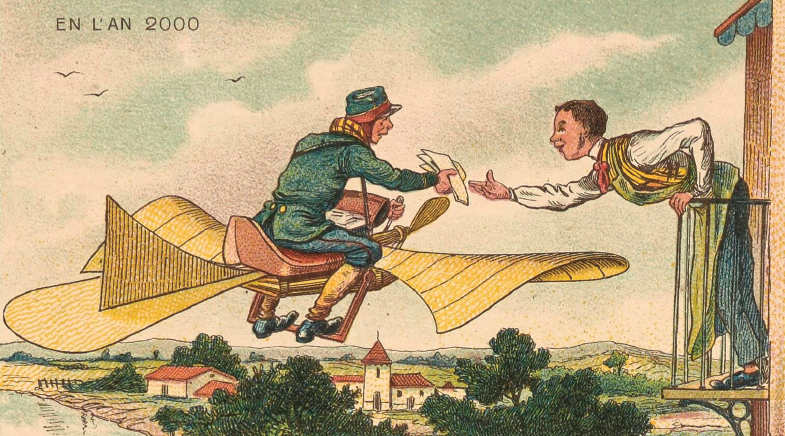

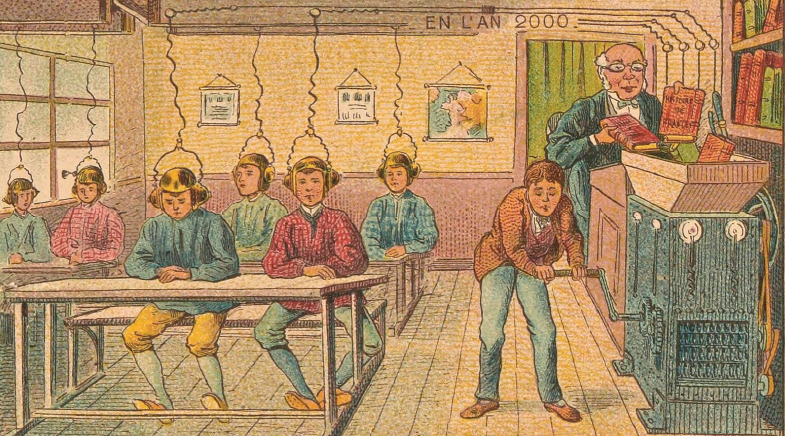

Every age has its own visions of the future; some far out ahead, and others nearer to the times. The year 2000 had excited the fancy of people towards the end of the 19th century, not least because it represented the turn of the millennium as well. In 1900, a group of French artists had tried to imagine the world a century later, representing their visions in postcards that were exhibited at the world exposition in Paris (bit.ly/1900-2000). These visions ranged from the prescient through the idiosyncratic to the ridiculous. The postcards depicted a world where mail was delivered in small planes to people's balconies; water buses were attached to whales for propulsion; houses were moving freely through the countryside like buses; and classroom lessons were 'delivered' to children's brains through wires by hand-turning a wheel. Such fanciful ideas probably reduced in number as the world went through the century.

The ideal city of the future will have plenty of vegetation and adequate public transport, and be resilient to droughts and floods.

In our own age, even as the new millennium approached, the year 2050 was chosen for imagining futures that were both grim and utopian. It was grim because of climate change and its potential impact. Urban planners and visionaries had known that, by the middle of the 21st century, the world would be hotter and wetter overall, with extremes of floods and droughts; more populous and iniquitous and, therefore, conflict-driven; and denser, with rapid people movement and, therefore, more prone to diseases and pandemics. On the other hand, the power of science and technology was expected to deliver a world where there was no cause for hunger; diseases would be under control and people would lead longer lives; and there would be fewer weather extremes because rapid warming would be held back through active interventions. As we approach mid-century, some of the dreams of these visionaries are making it to the drawing boards of real-world planners. Utopian cities are being deconstructed and reconstructed as real places to live and work in.

At present, there are about 10 projects that aim to build cities as cities should be: green and clean, quiet as well as connected; with enough options for work and social life. These cities include forested cities in China and Malaysia; bustling business districts like Masdar in Abu Dhabi; cities with no cars (or no roads for cars) like Net City in Shenzhen, China; green and disaster-resilient cities like New Clark City in the Philippines; and a net-zero sustainable city in Dubai. Running through them are themes that are thought to be essential to the ideal city of the future: full of vegetation, mobility centred on public transport or walking; and resilience to droughts, floods or pandemics. Ideas to build such cities were conceived early in the 21st century, when governments and technology companies conceptualised 'smart cities'. As happens with many early experiments, building a smart city or a sustainable city – or both together – from the ground up turned out to be harder than planned.

The central aim of most of these concepts was to get people to live close to places where they want to work, shop and socialise every day. In the words of the American urban designer Peter Calthorpe, people and economic activity needed to aggregate. In developed economies and many developing economies, most people cannot afford to live close to where they work. This creates urban sprawl, with enormous tracts of land being used to build independent houses and single-storey shops, with more space used for parking cars near homes and in sprawling parking lots. The U.S., where vast tracts of land are ostensibly available, was the main exhibit for wasteful urban sprawl. Within America, California exhibited this tendency at its worst. What could be achieved if all of it shrank into a smaller area? What if homes, shops, offices, hospitals, and schools all came close to each other in a community? There would be fewer single-family homes, fewer single-storey shops, more mixed-income areas, more room for natural surroundings. People will live closer together, use fewer cars, walk more, cycle more (Walking the green talk). And most certainly connect more.

Our past vision of today may have been fanciful, but it provides a sobering perspective when we now look ahead.

California, with nearly half of its greenhouse gas emissions coming from transport, is now re-examining its transport policies and patterns of land use in its Vision 2050 initiative. However, sprawl is not unique to America – or even to developed countries. China is full of urban sprawl, even in cities with many tall buildings. So is India, with its high-density cities like Delhi, Mumbai and Bengaluru, where economic activity is separated from housing and connected with each other through ever-widening roads with flyovers and underpasses and an increasing number of cars. It is precisely what the smart and sustainable cities of the future want to avoid. They want to put mass transit at the centre of urban design, get people to cycle or walk. These cities are experiments confined to small areas, but the ideas are thought to be scaleable. While the first set of city projects have not exactly gone according to plan, they are creating models for how to build the ideal city of the future. We know that all models are wrong, but some are also useful.

CLIMATE CHANGE HOTSPOTS

The city is not a modern phenomenon. Some ancient cities – like Rome – were thriving metropolises. For most of human history, however, the majority of the world population didn't want to live in them. In 1900, roughly 10% of the world's population lived in cities, according to the LSE Cities centre at the London School of Economics and Political Science. Now at least 50% of the population lives in cities, with the crossover from rural to urban happening around 2007, according to the United Nations. This figure will rise to 75% by 2050. By 2100, it will be 85%, with global cities having a billion more people living in them than the current total global population. Cities will clearly determine the Earth's future. Therefore, humans need to create the right kind of cities.

Putting mass transit at the centre of urban design serves more than one purpose.

Cities in developed countries have made the biggest contributions so far to global urbanisation. In high-income countries, more than 60% of the population was already living in cities by 1960, according to Our World in Data (bit.ly/cities-1960). Now 82% of their population is in cities; that figure is only 46% for India. With so many people living in them, cities are the main drivers of carbon dioxide emissions. According to the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), cities are responsible for 70% of the global carbon dioxide emissions. Transport is the main source of these emissions; buildings come second. Which is why putting mass transit at the centre of urban design serves more than one purpose.

Apart from emitting carbon dioxide, cities also produce enormous amounts of solid waste, consisting mainly of organic waste, construction waste, and non-biodegradeable products based on petrochemicals. Now at 2.1 billion tonnes a year, this municipal solid waste will increase to 3.8 billion tonnes by 2050, according to the UNEP Global Waste Management Outlook 2024 report. The direct cost of managing this waste is now $252 billion. When the costs of health and climate change are factored in, it rises to $361 billion. If the waste is not managed well, this cost is set to rise to $640.3 billion by 2050, but it will drop to $270.2 billion with proper intervention. A real circular economy would, on the other hand, generate a 'profit' of $108.5 billion a year.

Climate change makes cities vulnerable, especially if they are in coastal areas. The UN-Habitat World Cities Report 2024 offers some uncomfortable truths about cities and climate change. About 2 billion people worldwide will be exposed to a temperature increase of 0.5° Celsius by 2040, considering an intermediate emissions scenario. By 2040, more than 2,000 cities will be 5 metres above sea level, and 2,620 cities at 10 metres above sea level, which puts them at risk of flooding during storm surges. This is already evident in many cities; from 1975 onwards, they have been exposed to flooding 3.5 times more often than other areas. On the other hand, at least 600 cities will have drier climates by 2040; most of them are in the Mediterranean, western and southern Africa, and Central Asia. While the news about climate change becomes grimmer with each year, cities themselves make things worse with each passing year. According to the World Cities Report 2024, the share of green spaces in cities decreased from 19.5% in 1990 to 13.9% in 2020.

So urban designers and planners recognise that the world needs to do two things: make cities resilient to climate change, and stop them from becoming major drivers of climate change. Several cities are already on the way to reinventing themselves to be sustainable. They use more renewable energy, build more efficient public transport, make buildings more energy-efficient, create more green spaces and bicycle lanes, and improve waste management. Copenhagen, Canberra, San Francisco, Portland, Singapore and Vancouver are all making progress towards carbon-neutrality by 2050. In just the past decade, Santiago in Chile has cut air pollution by 70% through several measures, including switching to electric buses for public transport. Singapore is increasing its area covered by parks by 50% within a decade from 2020. Five Indian cities are part of the C40 network (bit.ly/c40-cities), a group of 100 cities with strong climate action plans.

Cities require substantial amounts of money to reinvent themselves. The World Cities Report 2024 puts this number at $2.5-5.5 trillion every year for improving infrastructure. In 2021-22, they managed to secure roughly one-fifth of this amount.

BUILDING MODEL CITIES

The new city of Songdo was first proposed in the late 1970s by a consulting firm in Incheon, a city near Seoul in South Korea, which houses its international airport. Seoul was getting crowded, and a new city needed to be built that could also serve as a model for future living. Land for this was to be reclaimed from the sea. It would be two decades before this was done. Work started on the New Songdo City in 2003. Multinational technology companies played a big role in the evolution of the concept into a smart city. In media discussions of the project, some of which this writer had sat through, technology companies used to emphasise the smartness of the concept. In short, the city would be able to take decisions by using information fed through ubiquitous sensors.

Songdo was also supposed to be a sustainable city with LEED certification (bit.ly/LEED-creds). This meant that the city should have at least 40% of its area as green spaces. It should also maintain a low overall carbon footprint, use local materials, build energy-efficient buildings, and so on. Waste was to go through underground tubes, be segregated automatically, and then incinerated. Sensors would monitor and feed information about every device in the city. Buildings could be controlled using cell phones. There were to be no cars in the city. It is an idea that almost all urban designers agreed upon: an ideal city should not have cars. Technology was at the forefront of everything. It was almost as if the city was to be built to showcase technology.

More than two decades after work started, Songdo is not fully complete. More than $35 billion has been spent, and the cost is estimated to cross $50 billion when the project is completed by the end of this decade (bit.ly/songdo-hubris), substantially more than originally planned. Life in the city is reported to be efficient, with all the quiet and beauty that one can expect from such an expensive city built from the ground up. However, there were problems too, not least because the residents wanted only basic services and were not quite willing to pay for all the "smartness" around them. Reclamation of the land stopped after a while because of environmental concerns. Songdo is now known as having spurred significant new research on smart city platforms – but also as an example of the limitation of technology companies leading smart city development (bit.ly/songdo-problems), and the dangers of not paying attention to market forces.

One of the more valuable lessons from smart cities that 'failed' spectacularly is to not put technology at the centre of the project.

Despite its drawbacks, Songdo is still alive, while other, no-less-ambitious, smart city ideas have failed. PlanIT Valley in Portugal, thought up by engineers with a dream of testing an Urban Operating System (UOS), failed through a mismatch between vision and execution, showing the futility of dreaming up technology in advance (amzn.to/4iLv96M) at a high cost. In interviews with this writer, PlanIT officials were effusive about how the UOS could remake the construction industry by documenting everything that happens during and after construction. Life in the city, according to them, will be as efficient as possible, and the city will necessarily be carbon-neutral. Unlike Songdo, PlanIT is now deemed a failure.

Cities like PlanIT were swimming against the tide. Throughout history, cities have adapted and grown as people moved in and changed their environment as they lived. There are not many successful stories of complete cities being first built for people to move in later. Malaysia built one of them at Johor in the southern part of the peninsula, costing $100 billion. The city is partly ready now, but nearly empty as few people want to move in; politics, too, has played a role here. Despite such failures, the experiment of building cities from scratch continues. Some of them will fail, but not without giving valuable lessons on how not to build cities. One of these lessons is to not put technology at the centre of the project.

On the other hand, some of these projects have also taken technology forward. They offered lessons on how to green cities (Greening our cities), how to use sensors, how to plan for transit, how to mix work and play in neighbourhoods. These lessons will be useful in subsequent greenfield projects, and in retrofitting existing cities as well.

BEYOND THE OBVIOUS

In the book Age of the City, published in 2023, economist and Oxford University Professor Ian Goldin and journalist Tom Lee-Devlin provide a series of recommendations for creating resilient cities in the future. As they see it, the car-based sprawl was "not only a colossal waste of resources, but also a social and environmental failure". Cars pollute the air, generate heat, take up too much space (one-third of the total space in a typical American city), and spend 95% of the time in parking spaces. Their first line of prescriptions are self-evident: mass transit, bicycles, walking. Embrace the 15-minute city, in the way Paris has done. But the authors say that such measures are not enough to touch the lives of low-paid workers, and thus leave many unresolved challenges for administrators.

So, to build resilient cities, governments have to make housing affordable and focus on mass transit. Making housing affordable can get people of all incomes to live in new developments, thereby preventing concentration of the poor in specific areas. Getting people to use mass transit widely requires the adoption of modern technology and may need shifting the revenue base from tickets to taxation. More than anything else, building resilient cities requires creating inclusive economies in districts, beginning with bringing high-skilled workers and well-paid jobs and then down to all levels. Needless to say, invest in education. Build societies and nurture communities.

In recent times, some urbanists have been propounding a concept called biomorphic urbanism (bit.ly/smart-urbanism). At its core is the idea that cities suffered by moving away from nature to concrete buildings, and that future cities need to reverse this trend. To accommodate a doubling of the urban population by 2050, the world needs to build about nine cities of the size of Hyderabad every year. To the new breed of urbanists, this is an opportunity to renew the human 'contract' with nature rather than move away from it. Biomorphic urbanism involves building ecosystems that are rooted to a place rather than superficial greenery. Planting trees may be a good start, as long as they belong to the place. Plants have a habit of attracting animals, including birds (Birds and the city).

Over the next 25 years, Indian cities will need to build as many buildings and facilities as they currently have.

Buried in all the conversations about how to build cities are some uncomfortable questions. Where should we build our cities? Human beings have, all through their history, lived near the coast. Roughly 44% of the world population lives along the coast. Sea level rise, which has so far been underestimated, threatens many of the most vibrant coastal cities. Some of the most vulnerable are Bangkok, Amsterdam, Manila, New Orleans, Cardiff, Shenzhen, and Dubai. At the next level of vulnerability are several cities in India, including Mumbai, Chennai, and Kolkata. Sea level rise is a long-term problem: water will continue to rise along the coastline for centuries after the world stabilises carbon dioxide emissions and starts bringing them down. Are fortifications enough to withstand storm surges? Is it sensible to let large coastal cities expand further?

In the next 25 years, India's urban population is expected to increase from just over 500 million now to about 900 million. This increase means that over these next 25 years, Indian cities would need to build as many buildings and facilities as they currently have. Building greenfield cities will provide an opportunity to experiment with fresh ideas, if executed with an eye on all the failures that have happened around the world. However, most of the development will happen in existing cities, especially the smaller ones. It is almost like getting an opportunity to build an entire country, once again.

See also:

Cities of the future

Fantastic plastic!

Power to the people

Walking the green talk

Greening our cities

Birds and the city

Cities' growth pains

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH