Managing cancer: the new regimen

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 04 issue 11 :: Dec 2025

A new mode of treatment advocates controlling cancer cells, instead of killing them.

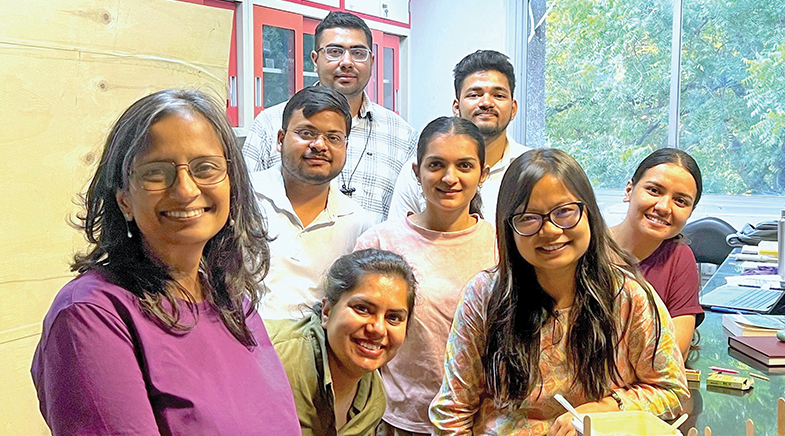

When Tapasya Srivastava's dog, Bosky, started behaving oddly — constantly sniffing at her, even pawing away at her blanket to do so — the Delhi University cancer researcher realised she needed to go for a health check-up. She knew that dogs had a keen sense of smell and could detect changes in volatile organic compounds emitted in body odours, which became more acute when there were cellular upheavals. She was also aware that women over 40 years of age were more vulnerable to breast and cervical cancers. So, she underwent a test — and, in 2018, was diagnosed with breast cancer.

Some researchers believe that to "tame" or "manage" cancer would be a better way to treat the disease than attempting to eliminate it entirely.

For over 15 years, Srivastava had been growing and studying cancer cells in Petri dishes in her laboratory. Cancer cells were now proliferating in her body. But, thanks to Bosky, the tumour had been detected at an early stage, which meant that the disease had not spread. She had the tumour removed from her breast and, as medically advised, underwent chemotherapy. Anticipating hair loss, she shaved her head.

Hair loss is a common side effect of chemotherapy. High doses of drugs in chemotherapy and targeted cancer therapy aimed at killing cancer cells often also lead to fatigue, nausea, weakened immunity, and organ-specific toxicities, and pose long-term risks of infertility. While killing cancer cells, the drugs also lead to a build-up of resistant cancer cells, which may cause the cancer to relapse. "If you kill all the drug-sensitive cancer cells, the resistant cells have an advantage: there is now no competition for them in terms of resources. So, they can grow (more profusely)," points out Mohit Kumar Jolly, Associate Professor at the Bengaluru-based Indian Institute of Science.

According to the International Agency for Research on Cancer, which is a part of the World Health Organization, there were close to 20 million new cases of cancer in the world in 2022, alongside 9.7 million cancer deaths. Resistance to therapy continues to be the biggest challenge in cancer treatment. Over the last 20 years or so, researchers have been looking at cancer as a highly dynamic and complex system. "Cells are not just sitting and waiting for us to give them a kill signal. Cancer cells are adapting their behaviour at different timescales," Jolly says. Cells respond to drugs and other stresses in multiple ways, he adds.

This understanding has led to the thinking that to "tame" or "manage" cancer would be a better way to treat the disease than attempting to entirely eliminate it, for killing cancer cells can lead to the build-up of drug resistance. The former approach attempts to maintain a stable population of both drug-resistant and drug-sensitive cancer cells through dynamic drug dosing, halting its progression by altering the microenvironment and disrupting other cues of cancer progression. Scientists are testing chemicals and drugs that turn cancer cells back into normal cells, working to ensure that the progression of rogue cells remains in check, being put to sleep or marked for degradation.

One such approach has worked well. This is a combination of all-trans retinoic acid and arsenic trioxide, which has effectively treated acute promyelocytic leukaemia or liquid tumours. All-trans retinoic acid, a molecule derived from vitamin A, has led immature cancer cells to differentiate into mature, normal white blood cells; arsenic trioxide marks cancer stem cells for degradation, preventing a relapse when cancer stem cells differentiate into cancer cells (bit.ly/Cells-Differentiate). Researchers are testing combination therapies where drugs that restrict cancer progression are administered along with reduced chemotherapy doses.

RESISTING RESISTANCE

Srivastava continues to wage a war against cancer — in her body and with science. In her lab, she has been examining how the low-oxygen microenvironment of a tumour favours its growth, proliferation, migration, and drug resistance. Cancer cells proliferate at a rate that outpaces the formation of new blood vessels. Therefore, oxygen demand exceeds supply, resulting in a low-oxygen environment. The low-oxygen environment forces cancer cells to adapt by activating various survival mechanisms, making them more aggressive and resistant to drugs. In a new study, yet to be peer-reviewed (bit.ly/Protein-Suppression), Srivastava's team has shown that Withaferin A (pictured, facing page), a compound extracted from the ashwagandha plant (Withania somnifera), suppresses the production of various proteins, such as NDRG1, produced under a low-oxygen environment. Through this action, Withaferin A can inhibit cancer cells from activating their survival mechanisms in a low-oxygen condition, stopping them from migrating and becoming resistant to drugs, and thus leading to their death. Based on these results, the team suggests that Withaferin A be used as a supplemental treatment with traditional chemotherapy to re-sensitise hard-to-treat tumours to drugs.

Scientists are testing chemicals that turn cancer cells back into normal cells, working to ensure that the progression of rogue cells remains in check.

Like Srivastava, Jolly is seeking ways to combat drug resistance in cancer. His interest in cancer research took shape in 2012 after he read Siddhartha Mukherjee's The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer, which mentioned drug resistance and cancer spread as primary challenges to cancer treatment. His interest, further honed during his PhD and postdoctoral research at Rice University, U.S., led him to his lab at the IISc in 2018, where he is examining these two challenges more closely. His team is trying to identify the various routes that cancer cells take to adapt to chemotherapy, radiation, and targeted therapies in a bid to block them. "Lock them in a given state as much as possible and then sort of develop drugs to minimise their impact," Jolly says.

Normal cells and early-stage cancer cells behave like epithelial cells by staying in one place and being tightly connected. However, cancer cells later undergo a transition to mesenchymal cells, making them mobile and flexible, and allowing them to move away from the original tissue. Working on drug-resistant breast cancer, Jolly's team showed that when a cancer cell in the breast undergoes the transition, it tends to lose its sensitivity to the drug tamoxifen. Therefore, the team suggested that inducers that convert mesenchymal cells back to epithelial cells be used together with tamoxifen to reduce the metastatic potential of cancer cells (bit.ly/Cell-Transition).

His lab is also trying to develop mathematical models of how drug dosages can be optimised so that both the drug-sensitive and drug-resistant populations remain. "Drug-sensitive (cells) can become resistant, and resistant can become sensitive; they can interchange their behaviours at some given timescale. So, we are also working on how we can prevent this adaptation from happening," he says.

RESTORING NORMALCY

Rather than killing cancer cells, Sanjeev Shukla at the Indian Institute of Science Education and Research (IISER) Bhopal is working to change the destructive behaviours of cancer cells. His team is looking at ways to "educate" cancer cells, forcing them to abandon the very tactics they use to survive and spread.

He believes that the future of cancer therapy lies not in killing cells, but in controlling them — introducing changes that halt metastasis and overcome resistance. "This approach promises to pave the way for smarter, less toxic therapies that prioritise a patient's quality of life," he says.

One of cancer's most dangerous behaviours is its runaway metabolism. To fuel rapid growth, cancer cells hijack a metabolic pathway called glycolysis. While inefficient, this process provides a fast source of energy and the raw building blocks for new cells. Shukla's team discovered a key link in this process in breast cancer cells: an enzyme called PKM2 that activates another enzyme, PFKFB3, putting the cell's metabolism into overdrive. Crucially, they demonstrated that blocking PFKFB3 with a compound called shikonin stops cancer cells from proliferating in the lab, effectively cutting off their supercharged fuel supply (bit.ly/Proliferation-Stop).

Another survival tactic Shukla's team is dismantling is the tumour's ability to grow its own blood supply — a process called angiogenesis. Tumours send out signals to sprout new blood vessels, which provide a lifeline of oxygen and nutrients. Shukla's lab investigates how cancer cells create these signals by "editing" their genetic messages through a process called alternative splicing. By identifying and targeting the unique proteins produced by this process, they aim to cut the tumour's supply lines and effectively starve it.

CUTTING THE CUES

Researchers are employing various approaches to manage the spread of cancer by limiting its growth and proliferation. Rajesh N. Gacche's interest was piqued by studies that showed apigenin — a plant flavonoid present in fruits, vegetables, and herbs — had anti-cancerous potential when tested on various types of cancer lines. Gacche, who works on flavonoids at Savitribai Phule Pune University, was curious to know the pathways through which this flavonoid limited cancer proliferation and delved deeper into the subject.

Apigenin treatment has been shown to increase the expression of genes that instruct cells to die, and reduce the expression that helps them survive.

His team assessed the effect of apigenin in triple-negative breast cancer lines. It found that apigenin could induce programmed cell death in cancer cells by generating reactive oxygen species and also inhibited the migration and metastatic potential of cancer cells.

Apigenin treatment has been shown to increase the expression of genes, such as caspases, that instruct cells to die, and reduce the expression of genes that help cancer cells survive.

Apigenin also arrested cancer cells at the G0/G1 phase of their cell cycle, obstructing them from multiplying. The team further found that this flavonoid could downregulate the expression of histone deacetylase and DNA methylase, epigenetic regulators whose expression caused the proliferation of aggressive tumours. The flavonoid also upregulated the expression of histone acetyltransferase, an epigenetic regulator that helped in tumour suppression. All in all, they demonstrated that apigenin acted in two ways to manage cancer, by shutting down the cancer's survival mechanisms and by activating its self-destructive or programmed cell death mechanisms. The researchers suggested further testing it in combination with other therapies (bit.ly/Apigenin-Impact).

Flavonoids are promising candidates for anti-cancer drugs due to their biocompatibility and low toxicity to normal cells. They selectively act on cancer cells as they have an unusual chemical balance between oxidants and antioxidants. Gacche's team has also demonstrated the mechanism by which alkaloids derived from the shrub Prosopis Juliflora suppress melanoma, and flavonoid galangin, found in honey and galangal, reverses mesenchymal cells into epithelial cells.

Gacche feels that the decision on whether to kill cancer cells or manage them should depend on the stage of the cancer. If the cancer is in its early stages, the effort should be directed towards killing the cells; when it has spread, the goal should be to manage it. However, he cautions that currently, 90% of cancer drugs in the market are centred on killing cancer.

"Drugs which inhibit the process of metastasis or the migration of cells are yet to evolve, and these drugs will essentially keep tumours in check," he says. The management of cancer, he believes, will increase the chances of a patient's survival.

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH