Microbes vs methane

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 05 issue 01 :: Jan 2026

Researchers are employing methane-eating bacteria to deal with the menace of the potent greenhouse gas.

Mary Lidstrom has devoted her career in science to studying 'methanotrophs'. She took interest in this group of microbes, otherwise known as 'methane-eating bacteria', as a graduate student back in 1973. Methane-eating bacteria have the ability to use methane as the only source of carbon and energy. "I've always been fascinated with the fact that they can grow on this incredibly simple compound," she says. "It's very challenging metabolically to grow on methane." At the time, relatively little was known about how they did that, she adds. Now, as Professor Emeritus of Chemical Engineering and Microbiology at the University of Washington, U.S., Lidstrom leads a research group developing a methane-removal solution using methanotrophs.

Methane (CH4) is the second-most abundant greenhouse gas in the atmosphere after carbon dioxide (CO2). Though methane contributes to about 20% of global warming, compared to 70% by CO2, it traps far more heat. Over a 20-year timeframe, one tonne of CH4 traps 80 times more heat than a tonne of CO2. "And even on a 100-year timeframe, it's still 30 times worse," says Lidstrom. "So, every molecule of methane that doesn't go into the atmosphere is equal to 30 to 80 molecules of CO2."

Though it is important to reduce the emissions of both these greenhouse gases, cutting methane is likely to be more rewarding in the near term in order to cool the planet. The atmospheric lifetime of methane is just 12 years, whereas carbon dioxide doesn't go anywhere for hundreds or thousands of years. "Going after methane in the short term will help us slow global warming while at the same time tackling CO2 because CO2 is a very long-term problem," says Lidstrom. "You can make an impact in a decade with methane."

Methanotrophs might be a get-out-of-jail-free card.

"They are basically almost everywhere," says Lidstrom. "They are in lakes and the oceans and rivers and streams. They're in soil. They're in the tundra."

By consuming methane, methanotrophs do the exact opposite of what microbes called methanogens do. Methanogens make methane. Methanogens thrive in landfills, flooded paddy fields, and the rumen of methane-belching cows, making landfills and agriculture key contributors of anthropogenic methane to global warming.

Due to the high-methane presence, even methanotrophs do well in paddy fields and landfills, cancelling some of the methane emissions. "You can think of them as a blanket around the earth, decreasing the amount of methane that goes into the atmosphere," Lidstrom says. "They do that naturally but they can't get it all."

Since methane emissions are on the rise, having increased 20% in the past two decades, technologies to remove methane from the air are being developed, but they are expensive, energy-intensive or inefficient. Scientists are turning to biological solutions, but a challenge is the low concentration of methane in ambient air. In the air we breathe, the methane concentration is 2 parts per million (ppm), says Lidstrom. "For an organism to grow, it's very low. It's a kind of starvation regime."

The air around landfills, paddy fields, coal mines, and oil and gas wells, on the other hand, has higher concentrations of methane – in the range of a hundred to a few thousand ppm. Lidstrom wants to remove methane from the air at these sites with the help of methane-eaters.

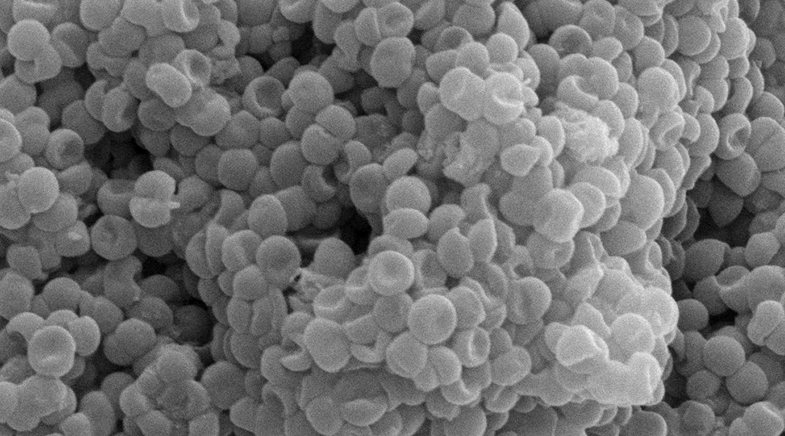

Lidstrom and colleagues screened multiple genera and species of methanotrophs for growth under a methane concentration of 500 ppm and selected the strain, Methylotuvimicrobium buryatense 5GB1C, for its promising characteristics (bit.ly/methane-candidate). "It grows well under a wide variety of conditions and many of these methane-eating bacteria do not," says Lidstrom.

M. buryatense 5GB1C can grow at a broad temperature range of 15-30°C and on methane concentrations of 200 to 2,500 ppm. The temperature range will help save energy that would otherwise be required for heating and cooling when culturing the organism for methane removal.

Simultaneously, the researchers have been testing various kinds of bioreactors in which to grow bacteria for the application (bit.ly/bio-reactor). Lidstrom would like to deploy the methanotroph-based bioreactor in a shipping-container-sized unit that will draw in and treat the methane-containing air near landfills. "Our goal is to be able to start to deploy in five years," she says.

When methanotrophs consume methane, they release CO2 as an end product, but they also use up some of the methane to grow. "Half of the methane that gets consumed makes more cells. And that's biomass," Lidstrom says. The biomass can be utilised for extracting single-cell protein for aquaculture and lipids for biofuel (bit.ly/methanotrophs). "The big advantage of the biological system is [that] it makes a marketable product," Lidstrom says. "That will drive scale."

YIELDS UP, EMISSIONS DOWN

Much like Lidstrom, Monali Rahalkar got introduced to methanotrophs during her PhD. She has spent the better part of her career since working on methanotrophs – isolating them from paddy fields and wetlands of India, and culturing them back in her lab. A scientist at the Agharkar Research Institute in Pune, Rahalkar has discovered new genera and species in the process.

Rahalkar and other scientists are applying methanotrophs to improve the yield of rice while reducing its carbon footprint. In a field trial near Pune, Rahalkar and colleagues got a 17% higher grain yield with an inoculation of the indigenously isolated methanotroph Methylomonas Kb3 than control plants (bit.ly/yield-gains).

What's more, the methanotroph enhanced the grain yield under a low nitrogen fertiliser application (50 kg per hectare, about half the usual application). Though the researchers did not establish nitrogen fixation in the field, their previous genome-sequencing study found that the methanotroph possesses nitrogen-fixation genes, explaining the added benefit (bit.ly/N-fix).

By consuming methane, methanotrophs do the exact opposite of what microbes called methanogens do.

Rahalkar has yet to measure the methane emissions from her methanotroph-treated plants. Meanwhile, String Bio – a Bengaluru-based biotechnology start-up – has shown methane emissions reduction with the methanotroph Methylococcus capsulatus. Their research, done in collaboration with researchers at the Vellore Institute of Technology, shows that CleanRise – String Bio's proprietary methanotroph-based biostimulant – improved rice grain yield by up to 39% and reduced methane emissions by 30-60% (bit.ly/GHG-emissions).

In the 2023 kharif season, for instance, the untreated plants emitted 226.97 kg methane per hectare, whereas the plants treated with M. capsulatus emitted 117.83 kg/ha.

Emissions of nitrous oxide, another potent greenhouse gas, also declined by 34-50% as a result of the methanotroph application. Rajeev Kumar, Scientist with String Bio and an author of the study, points out that typically nitrogen fertilisers are not completely utilised by crops. Much of the applied nitrogen, he adds, is either volatilised as nitrous oxide or leaches into the groundwater, causing environmental damage. Methanotrophs improve the nitrogen-use efficiency of rice and hence the yield.

The study found evidence of better yield and carbon fixation at molecular-level changes in the plant. A bunch of genes, including those related to photosynthesis and nutrient transporters, were upregulated in the methanotroph-treated plants.

BUNDLED SOLUTIONS

Every year, India's rice fields emit 3.9 tera (trillion) grams of methane. The traditional practice of cultivating rice in flooded fields creates conditions that encourage the growth of methanogens, the producers of methane.

Alternative rice cultivation practices are now being adopted. These are Alternate Wetting and Drying (where the field is irrigated, then left to dry) and Direct Seeded Rice (where seeds are sown directly into the field and irrigated like any other crop). These non-conventional practices reduce methane emissions and water use, but can have yield and soil quality trade-offs. They also emit more nitrous oxide.

The Institute for Governance & Sustainable Development (IGSD) in the U.S. is working with rice farmers in Sitapur and Jaunpur districts of Uttar Pradesh as part of a larger World Bank initiative. Their goal is to see if greater methane-emission reductions can be achieved by combining methanotrophs with non-conventional practices such as Direct Seeded Rice, both of which independently reduce methane emissions. The researchers also want to understand the impact of this bundled approach on water savings, soil parameters and grain yield, vis-à-vis traditional cultivation.

To this end, the IGSD is conducting a pilot using MT-22, a methanotroph formulation, which was identified as a methane-mitigating solution by scientists at the Indian Council of Agricultural Research-National Rice Research Institute in Odisha. "The methanotroph is naturally found in the Sundarbans," says Zerin Osho, Director of the India Program at IGSD. "It's extremely cost-effective."

The results of a trial conducted in the kharif season of 2025 (May–October) are currently being analysed. Osho's team is also collecting soil samples to find out how methanotrophs inoculated in the first season would impact the methanotroph-methanogen ratio in the next season.

Mitigating methane will not only curb global warming in the short term but also improve air quality and reduce economic risks, according to a recent study (bit.ly/climate-benefits).

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH