Outside the DNA

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 02 issue 05 :: Sep - Oct 2023

Research shows epigenetics is important for both our health and that of the next generation.

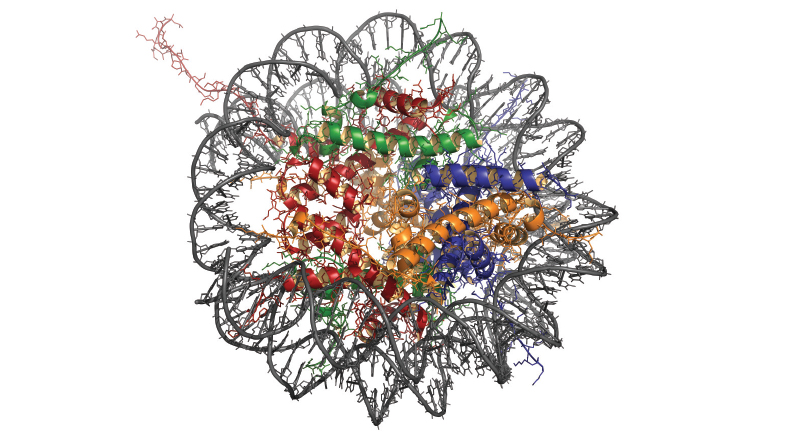

As a bachelor's student studying biology at the University of Delhi, one question fascinated Upasna Sharma quite early on: how is it that trillions of cells that form our bodies function in different ways despite all originating from a single cell, the zygote (fertilised egg cell). All the cells are genetically identical, carry the exact same DNA and yet heart cells are very different from the neurons, she says. This question has been like a beacon guiding much of her research career. "I may not always be directly working on it, (but) I guess we're getting closer to answering it," she says.

Now an Assistant Professor at the University of California Santa Cruz, Sharma studies the mechanisms by which parental environment (environment, exposures, habits, etc.) can influence the progeny. Her earlier work (bit.ly/small-RNA) has shown that male mice growing on a low-protein diet can affect the activity of genes involved in lipid and cholesterol metabolism in their offspring. In particular, she has shown that this effect travels from parents to offspring via small RNA molecules in the sperm.

The standard way of information transfer from one generation to another is via the DNA but in this case, it happened via sperm small RNAs. Small RNAs like these are epigenetic modulators, capable of transferring an additional layer of information to the information being passed on in the DNA.

Epigenetics (where "epi" means over or above in Greek) is the study of the processes that modify gene expression without changing the sequence of the DNA. Epigenetic modifications have zero effect on the core sequence of the DNA, but they alter how the same sequence is read and can have as drastic an impact as switching on or off of genes.

Small RNAs are not the only type of epigenetic modulators; there are others, for example, the tiny chemical additions that appear on the DNA or on the proteins attached to it. Together, these epigenetic modulators can alter the activity of genes in the DNA in not just parents but also in the offspring, as more and more evidence show.

A 2020 study in rats (bit.ly/epimutations) by Michael Skinner's lab at the Washington State University showed that exposure to vinclozolin, an agricultural fungicide, induces epigenetic changes that are inherited for three generations — up to the great-grand offspring. These epigenetic changes are induced via a host of mechanisms, including DNA methylation, expression of non-coding RNAs and modification of histone retention sites in the sperm. The researchers have done similar studies with "over 30 environmental factors and toxicants," says Skinner.

As of today, there is overwhelming evidence to support the existence of epigenetic inheritance in a variety of organisms. No organism studied has been found without epigenetic inheritance, including humans, says Skinner. What needs more clarity is the understanding of mechanisms and processes driving these changes. Even in instances where there is evidence for a particular mechanism in play, there may be more mechanisms that have not been identified due to the lack of appropriate experiments to probe it.

PAST ISSUES - Free to Read

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH