Sense and sensors

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 03 issue 01 :: Jan - Feb 2024

Researchers are working on effective biomarkers for diabetes and renal problems, as well as wearable biosensors that promise to ease testing.

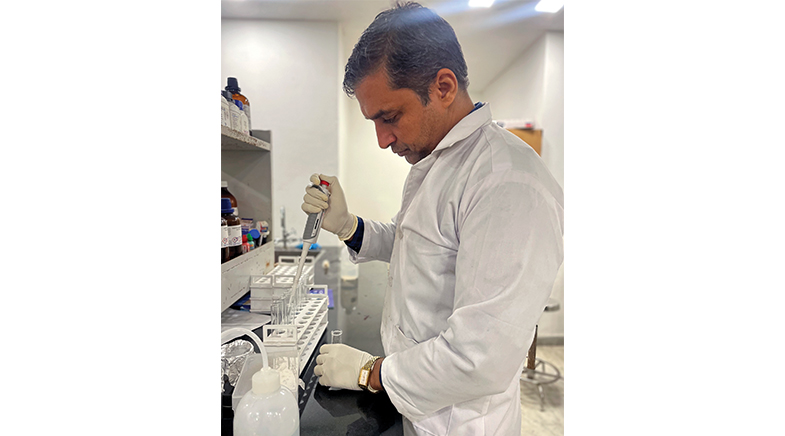

Deepak Kukkar lost his father to chronic kidney disease (CKD) three years ago. His father's condition exposed the biotechnology researcher from Chandigarh University to the problems of CKD diagnosis and treatment — and the imperative need for regular and invasive tests to check a patient's creatinine levels. Creatinine, a waste compound that muscles produce in day-to-day activities, normally passes out through urine. In people with kidney problems, it is not effectively cleared from the body, leading to a toxic build-up in the blood.

Kukkar, an Associate Professor of Nanobiotechnology, seeks to simplify creatinine tests, which are now mostly done with blood samples. He is developing biosensors that are efficient and easy to use. The current test used by pathological labs, called the Jaffe method, has several limitations. The test results can be confusing, for the levels can vary depending on a person's age, sex and muscle mass. Besides, the presence of biochemicals such as ascorbic acid, urea and glucose can also lead to inaccurate readings. The more effective alternatives for testing creatinine — such as high-performance liquid chromatography — are costly, time-consuming and labour-intensive.

"My idea in the long run is to develop a sensor that can reliably quantify creatinine levels using peripheral body fluids such as sweat, saliva or urine," he says. Since such tests are non-invasive, patient compliance is better, he says.

Body fluids are the focus of wearable biosensors, which are not just noninvasive but also enable constant monitoring.

Kukkar, working closely with researchers at the Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, and Hanyang University, South Korea, has developed two probes to measure creatinine levels effectively. While one of the sensors uses carbon dots (bit.ly/carbon-dots), the other is made with gold nanoparticles (bit.ly/gold-nano). These were tested with urine samples from 25 CKD patients and five healthy people, and it was found that the results were as good as those provided by the Jaffe method, he says.

In addition to refining the probes for creatinine, the team also plans to develop sensors for detecting and quantifying albumin in the urine. The albumin-to-creatinine ratio is a more precise indicator of impending kidney damage, Kukkar says.

SWEAT PATCH

Body fluids are the focus of wearable biosensors, which are not just non-invasive but also enable constant monitoring. For this, sweat is the best candidate, but the challenge lies in accumulating it for testing. Analysing sweat can help check a person's hydration levels, stress (as the stress hormone cortisol is released in sweat), and many minerals released in minute quantities.

Researchers led by Siddhartha Panda at the Department of Chemical Engineering of the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Kanpur have developed a novel sweat patch that can be used to collect and transport droplets that ooze out of sweat pores to a common point so that a sufficient quantity of it can be harvested for analysis. Inspired by desert plants and animals, the researchers developed a nanocomposite material of silicone polymer PDMS and titanium dioxide nanoparticles. A coating made of this nanocomposite solution is normally hydrophobic, but the scientists made some parts of it hydrophilic using a treatment involving ultraviolet radiation. This ensured that the material's surface consisted of both hydrophobic and hydrophilic parts. Droplets that fall on the hydrophobic parts bounce off and move towards the hydrophilic parts, says Panda. These eventually form channels, and sweat can be collected at one place.

To make the sweat collection efficient, the IIT team designed concave-edged wedge tracks, mimicking the peristomial structure of Nepenthes alata, a tropical pitcher plant. Their study appeared in the December 2023 issue of the Chemical Engineering Journal (bit.ly/sweat-alata). When the scientists tested a sweat patch of one-square-inch size using artificial sweat, it found that it could collect up to 90% of the fluid.

"Sweat does not have as many markers as blood, but it still has a reasonable number of markers," says Panda. Most of these biomarkers are also found in very low concentrations in sweat compared to that in blood. Developing technologies that can detect them at such levels will be a challenge, but scientists are interested in fluids such as sweat for the health information they contain, he says.

Panda adds that sweat-based devices are still emerging, with a few start-ups working in the area. Such devices could help check the hydration levels of people undertaking heavy exercises and soldiers posted in remote locations, alerting them when hydration levels are low.

Researchers in the U.S. have designed a ring-like wearable biosensor for monitoring oestradiol — a sex hormone that plays a key role in women's sexual and reproductive development — using sweat (go.nature.com/3Rn17cI).

MARKER FOR PREDIABETES

Work is also being conducted on effective biomarkers for prediabetic people. Currently, impaired glucose tolerance and glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) tests are used as markers for prediabetes, but these are found to be inaccurate in certain conditions; HbA1c, for instance, is influenced by disease conditions such as malaria, anaemia and haemoglobinopathy. A 2023 study funded by the Indian Council of Medical Research showed that about 15.3% of Indians were prediabetic (bit.ly/icmr-diabetes).

Researchers at the Shanmugha Arts, Science, Technology & Research Academy (SASTRA) in Thanjavur have been working on a biomarker that flags prediabetes and diabetes. The team, led by John Bosco Balaguru Rayappan, Professor at the School of Electrical and Electronics Engineering at the university, has developed an electrochemical biosensor that tests a blood sample for measuring methylglyoxal (MG), a highly reactive by-product of glycolysis (the process by which glucose is broken down to produce energy). The researchers have clinically validated it using blood samples of 350 patients. Over 20,000 times more reactive than glucose, MG readily reacts with lipids, nucleic acids and proteins, and is believed to be associated with many complications, such as atherosclerosis, vascular damage and kidney malfunction. MG is constantly removed in the human body, but this scavenging mechanism begins to impair at a prediabetic stage and further deteriorates among people with diabetes.

MG levels are found to be in the 1-1.2 micromolar (μM) range in non-diabetic people, and in the 2.8-4.2 μM range in those with diabetes. "Our work is at TRL (Technology Readiness Level) 6, and we plan to launch a device that can use MG as a biomarker within a year," says Rayappan, who, jointly with his colleague Srinivasan Vedantham, Professor at SASTRA'S School of Chemical & Biotechnology, has set up a start-up to take the innovation forward. Rayappan adds that a few medical doctors have evinced interest in testing the device.

Meanwhile, a start-up incubated at the Indian Institute of Science (IISc) in Bengaluru is already taking biosensing technologies to the masses. PathShodh Healthcare, co-founded by Navakanta Bhat, Professor at IISc's Centre for Nano Science and Engineering, and Vinay Kumar, the CEO of the firm, was set up in 2015 with the idea of making diagnostic technologies affordable and available for monitoring chronic diseases such as diabetes.

PathShodh, incubated at IISc Bengaluru with the idea of making diagnostics affordable, is taking biosensing technologies to the masses.

PathShodh has designed the first of-its-kind handheld medical device that can quantify multiple biomarkers associated with diabetes, kidney disease, anaemia and liver-related ailments in blood. "...our device is being used in the remotest areas of the country," Kumar says.

The device can read magnetic strips for biomarkers such as haemoglobin, glycated haemoglobin, blood sugar, and serum albumin using unique receptor chemistry developed at the institute. PathShodh has engaged vendors to manufacture the devices and is setting up a facility in Bengaluru where one billion strips can be produced in a year, Kumar says.

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH