Smart materials inspired by nature

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 04 issue 01 :: Feb 2025

From squids to leafhoppers, mimicking biological systems helps researchers develop sustainable composite materials and coatings.

It was the night before Christmas and chemist Daniel Samain, engrossed in his work at the National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) in Toulouse, France, realised all too late that he had not yet bought gifts for his children. Perhaps he could conjure up some whimsical curiosities in the lab, like maybe a parchment with a message written in 'invisible ink'. Samain set forth to write 'Joyeux Noël' (Merry Christmas in French) with a hydrophobic reagent that he was researching at the time. But when he dipped the paper in water, he was surprised to see that the letters had merged and the ink spread across the paper. It turned out that the reagent was acting not just as a coating but it was reacting chemically with the paper and spreading through it uniformly, repelling water completely.

This fortuitous discovery was made 28 years ago but it was only in 2020, when Samain met Romain Metivet, an investor interested in sustainable materials technology, that it resulted in the establishment of CelluloTech, a company making waterproof cellulose. Samain realised that he was effectively recreating what duck feathers do when they come in contact with water. Their glands secrete an oily substance that they rub over their feathers, which keeps them dry even underwater.

"If you put oil in water, they repel each other. We extract the same phenomenon at nanoscale," says Metivet, explaining how the start-up attaches one-nanometre-long fatty acid molecules around cellulose fibres. Traditionally, waxy coatings have been used to make paper water-resistant, but they add a few grams of weight per square metre. "This has the advantage of being very light in terms of material density. We use a few milligrams of a bio-based reagent per square metre, so the paper is still breathable and recyclable by the standard processes," he adds. The start-up is now partnering with packaging, tissue and diaper companies to license their technology.

Biomimicry is at the heart of what CelluloTech does, and so, it was a part of the 2024 Ray of Hope Accelerator cohort. The decade-old programme, hosted by the Biomimicry Institute, a not-for-profit based in Montana, U.S., fosters start-ups, like in biomimetic engineering, with applications in energy storage, bio-based building materials and sensors.

MIMICRY OF A KIND

Humankind has a long history of looking towards mechanisms and composite materials existing in nature to find solutions to its problems. One of the oldest examples is in textiles. Velcro – a hook-and-loop mechanism ubiquitous across industries today – was inspired by the cocklebur plant and how it clings to fur and clothing. Gecko feet have long inspired researchers to experiment with adhesive tapes. Spider silk is studied for its strength, and lotus leaves have sparked the invention of hydrophobic coatings.

More recently, there has been a global interest in the development of biologically inspired soft materials, a class of materials that includes biopolymers, composites and colloids. The Biological and Biomimetic Materials Laboratory (BBML) at Nanyang Technological University (NTU), Singapore, for example, studies natural materials with properties that have not been achieved in artificial materials and attempts to mimic their structural and biochemical principles. Led by researcher Ali Miserez, the lab studied squids – in particular, their sucker ring teeth that are made of proteins and embedded in the tentacles. In a paper published in Accounts of Chemical Research (bit.ly/squid-peptides) in 2023, Miserez explains how they exploited these molecular designs to engineer peptides that could self-assemble. Smart materials could be made out of self-assembling peptides with applications in targeted drug delivery, tissue regeneration and even self-healing robots.

When creating new materials, researchers look towards naturally occurring designs because, more often than not, these are the most energy-efficient ones, achieved through millennia of trial and error. At the Biomimetics & Dynamics Laboratory, Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Madras, Professor Sunetra Sarkar explains how the aerodynamics research group studying unmanned flights organically moved towards biomimetic mechanisms.

Sarkar was computationally looking at the motion or gaits of structures that are flexible, deformable and lightweight, under the effect of a flow field. She wanted to see if they could generate energy from the flow itself, without the need for a whole lot of input power to sustain the flight. "We did not start out considering a biomimetic motion; I was just enabling a model in which a perfectly deformable body is allowed to develop under flow field," says Sarkar.

However, the team found that by playing around with some parameters like the flexibility and inertia of the structure, the system showed biological gaits, like those of the Carangidae or Anguillidae fish families. "So, it essentially looks like when these biological gaits are followed, in some clever way, the body is extracting the maximum energy from the fluid around it," she says; this makes it the most energy-efficient and sustainable mechanism possible. "Nature must have done a design in the background, and come up with these gaits because of certain reasons. For us, that reason is getting the maximum power output."

GREEN CHEMISTRIES

The properties of adhesion and repulsion, in particular, have led to many innovations by biomimetic chemists and engineers. So, it was a subject of interest for Lin Wang, a post-doctoral scholar at The Pennsylvania State University in the U.S., who had been researching ways to recreate hydrophobic surfaces found in nature. He zeroed in on the leafhopper for the water-repelling nature of its secretions, which are made up of microscopic granules called brochosomes.

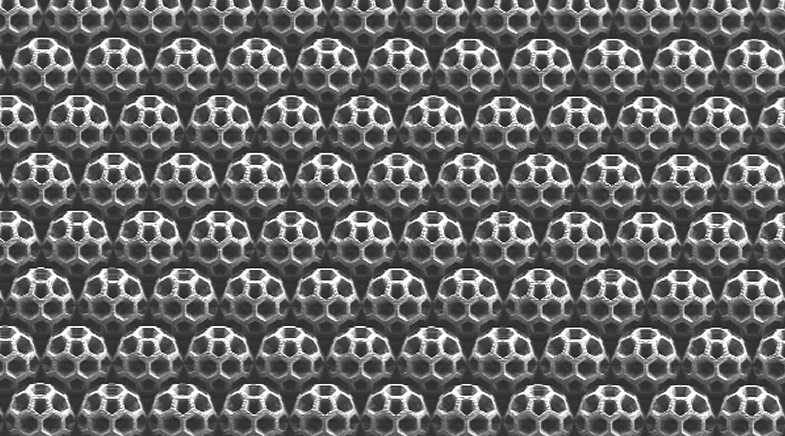

Wang was obsessed with how religiously leafhoppers would coat themselves, and their eggs, in brochosomes: he was convinced there was something useful to humans there. His study, however, revealed something even more interesting than its hydrophobicity – its optical properties. He found that brochosomes, owing to their soccer ball-like structure, scatter most of visible light and absorb ultraviolet light. For the first time since its discovery in the 1950s, Wang succeeded in synthetically recreating a brochosome using microscale 3D printing.

The soccer-ball structure, with through-holes (or pores), is the key to its optical properties. It creates two effects: one, the size of the brochosome is similar to the wavelength of visible light, that is to the order of 500 to 600 nanometres. "This means that the leafhopper is able to scatter most of the light that falls on it, and a predator would only be able to see a section of light reflected back. This is effective for camouflage," says Wang. The second effect is due to the through-hole, or pore, diameter being to the order of 100 to 200 nanometres. "So, any light with wavelength similar or smaller to the pore size, such as UV light, gets absorbed into the holes," he adds.

Wang hopes that synthetic brochosomes will one day be useful in creating optical materials, UV-ray blocking technologies in sunscreens and as coatings on solar panels to harvest more energy. His research, published in PNAS (bit.ly/brochosome-design) in 2024, was performed under Tak-Sing Wong, Professor of Mechanical Engineering and of Biomedical Engineering at Penn State, who also heads the Laboratory for Nature-Inspired Engineering there.

The lab's efforts to recreate the brochosome span a good part of the decade. It has previously also experimented with replicating the slippery surface of a pitcher plant, creating repellent coatings. It has so far been used in protecting medical devices from biofouling and by shipping companies to save fuel cost by preventing barnacle adhesion to the bottom of the ships.

When creating new materials, researchers look towards naturally occurring designs because these are some of the most energy-efficient ones.

"One big demonstration for us was creating portable toilets for areas with water scarcity. We coated them with repellents that would discourage human waste from sticking to its surface. This could reduce the consumption of water for cleaning bathroom fixtures by a significant percentage," says Wong. The lab's work spun-off into a start-up in 2018, called spotLESS Materials, specialising in bathroom maintenance kits.

Having now shifted focus to synthetic brochosomes, Wong hopes there will be a real-world application for it soon, one of which is information-encrypting. "You can use the synthetic brochosome to create an encryption pattern, which will only be visible under light of a certain wavelength, in order to identify the authenticity of certain high-value items, or for defence applications where you need to transmit information," he says.

Anti-reflective coatings are already popular in the optical industry today. However, Wong is confident that brochosomes will step up the game. "Unlike most coatings that only work under a range of angles of incoming light, brochosomes' uniform and symmetric 3-dimensional structure can reduce the reflection of light coming from all directions," he says.

This, he says, is why nature is a master of materials and nanotechnology. "The good designs stay over time, and the bad designs are thrown away; that is the basis of evolution."

See also:

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH