Salve from the soil

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 04 issue 09 :: Oct 2025

Streptomycin saved countless lives, but its October 1943 discovery by a PhD student at Rutgers was mired in a bitter battle.

The basement lab at Rutgers was dingy, and its sink usually overflowed with glassware. It had only one human occupant: 23-year-old PhD student Albert Schatz, who often slept overnight on a wooden bench squeezed into a corner. Its other occupant was H37, a highly virulent tuberculosis (TB) bacterial strain.

The year was 1943. The Second World War was at its bloodiest. Soldiers not killed by bullets were being decimated by invisible bugs. The TB bacterium was the worst: it resisted every available antibiotic. Schatz, who had briefly worked as a lab technician in the U.S. army, was determined to find a cure.

When Schatz joined Rutgers, his PhD advisor, Selman Waksman, had already tasked his students with screening soil samples for microbes called Actinomycetes that could produce antibiotics. They initially isolated two chemicals, but both were toxic to animals. After being discharged from the army in June 1943, Schatz returned to Rutgers and began his own experiments.

In August, he began culturing strains of a bacterium called Streptomyces griseus taken from two sources: fresh manure found near the lab and a throat swab from a healthy chicken borrowed from a student in a neighbouring lab. At around 2 pm on October 19, Schatz realised that he had a new antibiotic: the chemical he had extracted from the strains effectively killed TB bacteria. He immediately sealed the test tube containing the extract and informed Waksman.

IRONY LOST

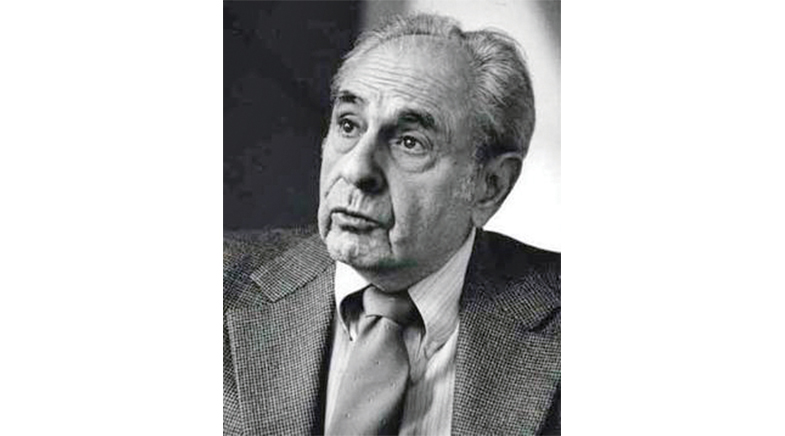

While Schatz fought with Waksman for credit, there was one more person who was sidelined. Elizabeth Bugie (pictured) was the second author on the original streptomycin paper that the trio published. But she was told that it was "not important" to have her name included in the patent application because she would soon get married and have a family (bit.ly/Elizabeth-Bugie).

Animal tests with collaborators at the Mayo Clinic showed that the new antibiotic, named streptomycin, was exceptionally powerful, and the pharma company Merck stepped in to mass-produce it. Schatz and Waksman applied for a patent together, but the latter convinced the former to sign over his royalty rights from sales of the drug to the university. Waksman then began publicising the discovery, while Schatz continued producing cultures for Merck.

Behind Schatz's back, however, Waksman secretly negotiated with the university to get 20% of the royalties. When Schatz realised this — first becoming suspicious when Waksman kept sending him $500 cheques — he was furious (bit.ly/Scientific-Deceit). He confronted Waksman, but the latter accused him of "grandstanding". Feeling betrayed, Schatz sued both his mentor and the university. During the trial, Waksman continued to downplay Schatz's role, telling him that his contribution was "not substantial" and that he was one of "many cogs in the great wheel" of the lab's research on antibiotics (bit.ly/Waksman-TB).

DENTAL DENIAL

After Schatz moved to Chile in 1962, he also contributed to dental research. But his controversial claims landed him in hot water. He suggested that fluoridation of drinking water was ineffective at preventing tooth decay and even led to increased cancer and deaths. In 1973, the U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare clarified that water fluoridation posed "no hazard relevant to cancer causation".

The lawsuit was settled out of court in Schatz's favour, naming him co-discoverer of streptomycin and granting him royalty rights, but it also set him up for scientific ostracism. He struggled to find an academic position in the U.S. and ended up moving to South America. In 1952, Waksman alone received the Nobel Prize, amidst much criticism (bit.ly/Nobel-Criticism).

It was only in the 1980s that researchers began crediting Schatz. In 2010, author Peter Pringle uncovered Schatz's original lab notebooks tucked away in the Rutgers library, which provided the final piece of evidence (bit.ly/Lab-Notebook). It was an entry dated August 23, 1943, titled Experiment 11: Antagonistic Actinomycetes, marking the start of the young student's experiments on the strains that produced the life-saving drug.

Ranjini Raghunath is a Bengaluru-based science writer and editor.

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH