Spaghetti, anyone?

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 01 issue 04 :: Jul - Aug 2022

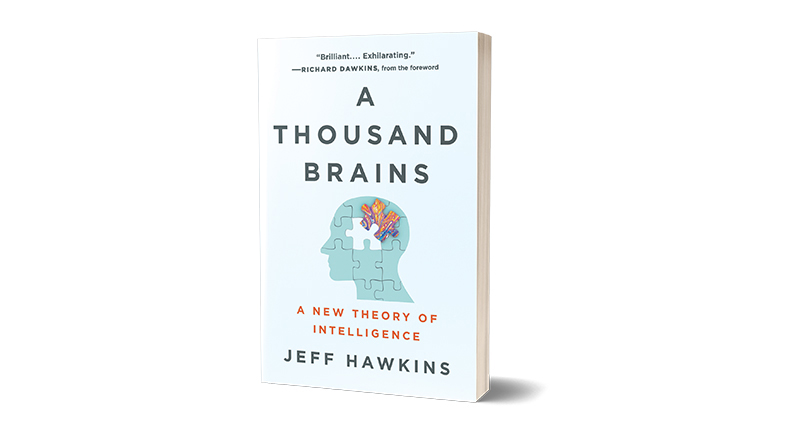

American neurologist Jeff Hawkins takes an intriguingly new approach to the brain.

Computer scientist and neurologist Jeff Hawkins lays out an intriguing hypothesis about the nature of brain function in this bestseller. Hawkins and the team he leads at the California-based research institute, Numenta, propose a radically new model of learning and prediction.

Numenta is trying to reverse-engineer the way the neocortex functions, in order to develop machine intelligence. Researchers from there have published several highly cited, peer-reviewed papers to substantiate their hypothesis, although there are gaps in the model.

We have a fair idea of the brain's physical structure. It is composed of multiple parts, with the older bits common to mammals, reptiles and birds. Mammals also have the neocortex, a 2.5-mm-thick, six-layered structure consisting of neuron cells overlaid across the older parts.

The neocortex is organised into hundreds of thousands of tiny 'cortical columns'. One analogy in the book compares the neocortex to a mass of spaghetti with the noodles consisting of cortical columns, which are stuck together since neurons are connected to each other.

LEARNING TO PREDICT

Sensory inputs – all that we see, hear, smell, touch – are processed in specific areas. The neocortex uses those inputs to 'learn', and that learning is then used to 'predict' what will happen, moment by moment, as we sip coffee, hit balls with bats, pluck sitar strings and so on.

There's a lot we don't understand about this, and Hawkins & Co. have been looking for insights. Hawkins believes that the generally accepted picture of how our brains work is wrong. Early on, he cites an assertion by the great neuroscientist, Dr Vernon Mountcastle, who discovered the cortical column structure.

Mountcastle believed that we learn everything the same way, whether it is abstract mathematics or motor skills. He thought the learning process must be the same, or very similar, because cortical columns are all very similar, even though different columns process very different inputs. The brain must therefore use the same processes to learn simple stuff, and also more complex, conceptual things since it uses similar tools for both.

The framework of the 'thousand brain theory' may help develop insights into hitherto-intractable problems.

Numenta's concept as described by Hawkins is as follows. Each cortical column is an individual computing 'chip', which builds its own model or reference map. Every column has a unique frame of reference, and each receives different sensory inputs and perspectives, which it uses to build reference maps. Also, each column is connected in multiple ways to other columns.

Different columns therefore make different predictions. What will the next note of a melody be? Where is the nearest toilet? Then the brain 'votes', processing those predictions and generating consensus.

In this model, the brain acts like an electronic voting machine, though it weights the 'count' of votes. The assertion that the brain must choose by 'voting' among thousands of different thoughts and predictions makes intuitive sense (which, of course, doesn't necessarily mean that it is correct).

Even while sitting in your own house, your brain is referencing hundreds of inputs and tracking many objects, every instant. This is unconscious, until it's not. You notice your phone only if it rings; you note a window is open only if the wind blows through. But some part of your brain must register the mobile and track events at the window even if 'nothing' is happening. Or else, how does your brain flag a change of state when something changes?

This framework – the thousand brain theory – may help develop insights into hitherto-intractable problems. While the brain can predict the taste of strawberry ice cream, it can also predict what might happen if hydrogen plasma is confined in magnetic fields, or if a central bank hikes the interest rate.

SELF-LEARNING AI

If Numenta or somebody else using this thousand-brain approach can reverse-engineer a better working model, we would be closer to building self-learning artificial intelligence (AI), machines capable of general intelligence, and we may improve human pedagogy as well.

In the latter part of the book, the computer scientist in Hawkins takes over from the neurologist as he discusses the implications of machine intelligence. Unlike many AI experts, Hawkins is confident that super-intelligent computers will not, in themselves, pose a threat, and thinks that human-machine intelligence can yield powerful and beneficial synergies.

Although it's not particularly long, this is a sweepingly ambitious book in its theme and scope. It’s a must-read and interested readers can follow through on the bibliography and suggested readings for deeper insights.

Devangshu Datta is a consulting editor and columnist with a focus on STEM and finance. He is partial to chess, bridge and maths.

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH