See how they move

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 05 issue 01 :: Jan 2026

From slithering tubes to moving with legs: the wondrous evolution of locomotion.

Living in the tropics, even in a big city, means constantly encountering a range of animal life. A banana, left partly unpeeled by a window, will have crawling fly larvae in a day – if a macaque hasn't attacked it first. Outside, birds will be lined up on cable TV wires, and squirrels will scurry up vertical surfaces with ease. If you are observant, the foliage around you will likely have a slithering grass snake or, more dangerously, a viper. On the cement path that you restrict yourself to, you will chance upon a millipede purposefully crossing to the other side, its over 50 pairs of legs not missing a beat. Looking up at dusk, you will see flying foxes going home; looking down, you will see your street dog, cats, bandicoots, and more. Who needs a zoo?

Many questions will arise in the curious mind. Why do worms not have legs at all, and why do millipedes have so many? Why aren't there animals with an odd number of legs? Are snakes limbless lizards – or did lizards gain legs? Why don't animals have wheel-like limbs and a steering wheel?

The earliest animals likely lacked a defined front and rear, existing as either asymmetric or radially symmetrical forms. From these forms, there was a transition to a form of bilateral symmetry. That is, if we sliced the animal along the 'long' axis, each half would be identical to the other. The earliest common ancestor of all bilaterian animals, called Urbilateria, is thought to have been simple, seabed-dwelling, and lacking complex organs like a through-gut, a cavity for internal organs, or specialised excretory systems. This view has long been supported by the morphologically austere flatworms and other animals that exist today. A species of marine worm, Xenoturbella bocki, has a simple sac-like gut and no anus, brain, or circulatory system. Does their simplicity reflect the ancestral condition? Under this model, the evolution of the early worms and related animals was through an increase in complexity from, perhaps, a ciliated microscopic larva that settled on the seafloor and began to crawl.

COMPLEX ORGANISMS

To evolve from a relatively simple, bilaterally simple 'tube' into a specialised animal with head, thoracic and abdominal segments, with appendages for walking or flying, requires a complex molecular toolkit of genes and their products that drive this process. One would expect that this molecular toolkit would come about along with the complexity in animal morphology. Genomic sequencing of X. bocki has revealed that it possesses a complex, "bilaterian-typical" genome, with a nearly full complement of key developmental signalling pathways used in complex animals as well as a diverse array of gene-regulatory factors typically associated with complexity. This implies that the genetic machinery for building nervous systems, muscle, and potentially even distinct body regions, was present at the very dawn of bilaterally symmetric organisms, even if the use of this machinery for morphology was not evident in the first non-segmental worms. One explanation, among others, is that this genetic machinery evolved for use in other aspects of the marine worm's life and was then taken over for building complexity. The issue is not closed as new genomic and developmental datasets continue to test whether their simplicity is ancestral or secondarily reduced, but the "early‑branching bilaterian" placement is now the reference position used in most evolutionary discussions.

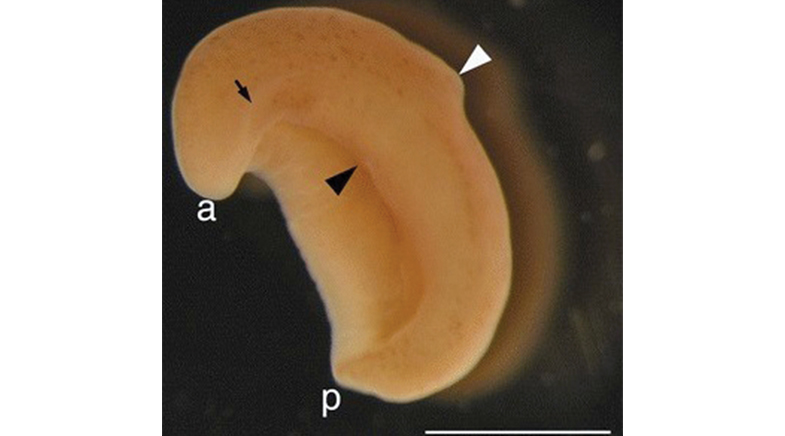

The evolution of ancestral forms of these marine worms requires the definition of the anterior-posterior (front and back) axis and the dorsal-ventral (the top and bottom) axis. Molecules that have a high concentration at the anterior, because the cells that make these molecules were at the front, were likely used in head-specification, and as the concentration of these molecules decreased along the axis, the tail was specified at the lowest concentration. Concentration gradients of other molecules from 'top' to 'bottom' similarly specified the dorsal-ventral axis. This molecular coordinate system allowed for the regionalisation of the body without segmentation. Imagine the animal as a tube with only labels: top and bottom, front and back. In non-segmental worms, the gut and muscles are patterned by these gradients, but the tissues remain continuous. The evolution of this continuous, axial organisation allowed for the first directional locomotion, gliding via cilia or undulatory swimming using longitudinal muscles, setting the stage for the later innovation of modularity in movement.

MECHANICS OF MOVEMENT

The transition from a non-segmental to a segmental organism was a major next step. The very simply patterned tube, with just a top and bottom, front and back, was patterned into segments along the anterior-posterior axis and also into units from the dorsal to the ventral, resulting in a 'grid'. Segmentation is intimately linked to the evolution of the coelom or the fluid-filled body cavity. This compartmentalisation is vital for locomotion. It allows each segment to function as an independent hydrostatic skeleton. When circular muscles in one segment contract, that specific segment elongates, pushing against the substrate. If the coelom were continuous (as in non-segmented worms), pressure would dissipate across the whole body, making precise peristalsis impossible. Thus, the evolution of segmentation was likely driven by the biomechanical demands of burrowing. The ability to localise pressure changes revolutionised animal locomotion, allowing for the invasion of seabed substrates and the subsequent diversification of worm-like forms.

A segmented body is of limited use if every segment is identical. The true power of the segmental body plan lies in the grouping of segments into functional units (for example, head, thorax, abdomen). This regionalisation is orchestrated by a family of genes, called Hox genes, that provide each segment with its specific identity. This allowed each segment to diversify its properties.

The X. bocki possesses a complex, "bilaterian-typical" genome, with a nearly full complement of key developmental signalling pathways used in complex animals.

With the body axis defined and segmented, the final major innovation was the outgrowth of appendages. The evolution of limbs represents the co-option of a "body wall outgrowth" program at specific locations in specific segments. While the legs of a fly, the parapodia of a worm, the fins of a fish, or the wings of a bird are structurally different (and evolved independently as organs), they share the same genetic machinery. This outgrowth is regulated by the distal-less gene (Dll, so called because distal appendages are absent when the gene is mutant), which is universally expressed in the distal tips of developing appendages. Dll expression marks the outgrowth of appendages in the most ancestral animals to the most derived. This suggests that the earliest bilateria had a program for making "protrusions", such as sensory tentacles or simple bumps. As different lineages evolved legs, gills, or fins, they independently recruited this ancient Dll module. This explains why disparate limbs look different but are built by the same genes.

SCAN & WATCH

The evolution of the four-legged limb from the paired fins of fish is a significant event in vertebrate history. In jawed fishes (like sharks), paired fins are supported by cartilaginous radials. The transition to land involved the evolution of the wrist/ankle and digits. This structure has no direct equivalent in the fish fin. It arose through the evolution of a late-phase expression of Hox genes, which were earlier used to give segments their identity.

OUT ON A LIMB

Having established the genetic and developmental foundations, we can now address the specific questions regarding the diversity (and absence) of limbs in various animal groups.

Why do worms not have legs at all, and why do millipedes have so many? The ancestors of earthworms transitioned from a marine lifestyle to a terrestrial, burrowing existence. These ancestors, like today's bristle worms, possessed well-developed, paddle-like limbs used for swimming and crawling. In the dense, high-friction environment of soil, fleshy limbs are a liability: they increase drag and are prone to damage. Earthworms lost their 'limbs' through secondary regression. They evolved a locomotor strategy based on peristalsis, or rhythmic waves of contraction acting on a hydrostatic skeleton. Millipedes (Diplopoda) represent the opposite extreme: they retained the ancestral trait of having limbs on almost every segment. Unlike insects, which have a fixed number of segments upon hatching, millipedes add segments throughout their lives (anamorphosis) via a posterior growth zone. Millipedes are detritivores that burrow through tough leaf litter and soil. Their "many-legged" design allows them to generate an immense pushing force. By having dozens of points of contact with the ground, they can anchor themselves firmly and push their heads into the substrate like a battering ram. The sheer number of legs provides the traction needed to overcome soil resistance.

Why are there no three-legged animals? The bilaterian body plan is constructed around a midline. Genes that specify limb formation (Hox, DII) are expressed symmetrically on the left and the right sides. To produce a single, functional medial leg would require breaking this symmetry in a way that conflicts with the fundamental patterning of the nervous system and gut. The signalling pathway for left-right asymmetry controls the placement of internal organs (like the heart), but does not typically uncouple the development of the body wall. Starfish have five arms, an odd number. This is not a violation of bilaterian rules but a modification of them. Starfish larvae are bilaterally symmetrical. During metamorphosis, the left side of the larva grows to become the oral disk of the adult, while the right side degenerates. The five-fold symmetry is a secondary derivation.

Snakes are phylogenetically embedded within the lizard clade (Squamata). They are, effectively, highly specialised lizards that have lost their legs. The fossil record contains snakes with legs, such as Najash rionegrina (which had hind limbs and a pelvis). These transitional forms prove that snakes evolved from four-legged ancestors. There is now genetic evidence on how this could have happened.

THE DEAL WITH WHEELS

The absence of wheels (macroscopic rotary locomotion) is one of the few "forbidden phenotypes" in organismal-level biology. A true wheel must rotate freely 360 degrees around an axle. This poses an insurmountable problem for a multicellular organism: how can it supply the rotating part with blood and nerves? Any vessel or nerve crossing the axle would be twisted and severed by the rotation. Without a blood supply, the tissue would die; without nerves, it cannot be controlled. Wheels are efficient on prepared, flat surfaces (roads). In the natural world — filled with rocks, roots, swamps, and sand — wheels are often inferior to legs. Legs can step over obstacles, while wheels must roll over or around them. The biological cost of evolving a complex rotary joint is not justified by the performance on rough terrain. Nature has invented the wheel, but only at the molecular scale. The bacterial flagellar motor is a true rotary engine. It consists of a rotor and stator made of proteins, powered by a proton gradient. It spins at thousands of revolutions per minute! At the scale of a bacterium, nutrients are delivered by diffusion. The "wheel" (flagellum) is a dead protein filament, not living tissue, so it does not need a blood supply. The vascularisation constraint does not apply at the cellular level.

A monthly column that explores themes on nature, nurture and neighbourhood in the shaping of form and function.

Locomotion, in all its diversity, points to how animal patterning and development are modular. A sheet of cells is shaped into a tube, and the tube is patterned into a grid with a specific identity associated with each grid, as in a map. Genetic and molecular modules act on each grid differently, according to its context, morphing their form to give us the wonderful range of appendages we see in animals around us.

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH