Why it went viral

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 04 issue 08 :: Sep 2025

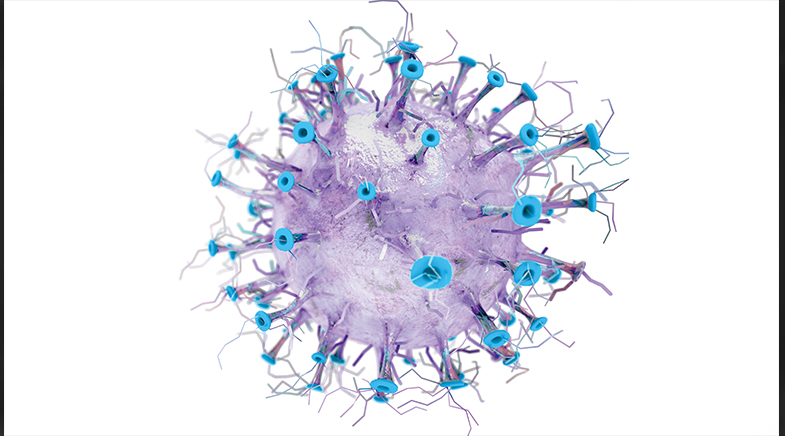

A study explains why Omicron was less severe than the Delta variant.

Viruses and hosts share a curious relationship. Virologists theorise that while viruses initially cause severe diseases, they adapt, leading to milder diseases, and ultimately coexist with the host. Now, a collaborative study by scientists from the U.K. and India explains how a genetic change helped the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2 do the same — spread faster yet cause a milder infection.

The COVID-19 pandemic period witnessed the emergence of various SARS-CoV-2 variants, one after another. Each one behaved differently. While the alpha variant spread more rapidly, the beta and gamma variants evaded immunity. Delta was highly transmissible and more severe. Omicron spread the fastest but was milder. The coronavirus infects cells using its spike protein, which consists of two subunits: S1 and S2. The S1 subunit helps recognise and bind the ACE2 protein on human cells. After binding, a human enzyme cleaves the spike protein at specific sites, releasing the fusion peptide from the S2 subunit. This peptide, along with other proteins, facilitates the fusion of the viral cell and the host cell, thereby infecting the latter.

Although most SARS-CoV-2 variants follow this cell fusion route, earlier studies had shown that the Omicron virus infects cells by endocytosis — not by cell fusion but by tricking the host cell into swallowing it.

A genetic change that altered an amino acid in the spike protein adversely affected the spike's ability to infect via the cell fusion mode.

The new research, by scientists at the University of Cambridge, U.K., and the CSIR-Institute of Genomics and Integrative Biology (CSIR-IGIB), was published in the journal Cell Reports (bit.ly/Omicron-evolution). It shows through molecular simulation how a genetic change that altered the amino acid present at the 812th position of the spike protein caused expected changes in the fusion peptide and also led to an unexpected conformational change in the cleavage site, impairing the cleavage required for cell fusion. This change adversely affected the spike's ability to infect via the cell fusion mode. This mutation also allowed Omicron variants to evade neutralising antibodies in vaccinated individuals.

Delta was seen to cause cell fusion, which damaged the tissues. "This research shows that because of this mutation in spike protein, the ability to cause cell fusion was lost and the Omicron virus attenuated partly," says Shashank Tripathi, Associate Professor at the Bengaluru-based Indian Institute of Science. This explains why Omicron was less severe than the Delta variant. An expert in virology, Tripathi is not associated with the study.

Lipi Thukral, Associate Professor at CSIR-IGIB and a member of the research team, notes that a single amino acid substitution can affect multiple phenotypes. The team is now seeking to understand how diverse genetic changes affect the behaviour of the virus.

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH