3D-printed food is now on the menu

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 03 issue 06 :: Jul 2024

Research in food printing is scaling new dimensions, but the market is waiting for the ink to dry.

C Anandharamakrishnan's interest in food took a new dimension in 2017. A chemical engineer by training, he was no stranger to food science, but his focus had been on nutrient delivery systems. At the Council of Scientific & Industrial Research's (CSIR) Central Food Technological Research Institute, based in Mysuru, he was researching the absorption of iron and other micronutrients by the body when he felt the need for an artificial stomach to validate his experiments. 3D printing, or additive manufacturing, was emerging in the 2000s as a tool for creating customised machines. He used the technology to create an artificial gastrointestinal system named ARK.

In 2017, when he took over as Director of the National Institute of Food Technology, Entrepreneurship and Management (NIFTEM)-Thanjavur, 3D food printing (3DFP) technology was an emerging area of research. In his new role, and given his experience in additive manufacturing, he understood the potential of the technology to create foods of the future.

Printers those days were expensive, had to be imported and came with limited features. So, Anandharamakrishnan and his team decided to fabricate their own printer – the Controlled Additive Manufacturing Robotic Kit. The machine is now joined by four other in-house-designed printers, each with newer features, like in-built temperature control and multi-head nozzles that allow for more than one ink to be printed simultaneously. The latest has a co-axial nozzle, which allows for printing of two different food inks, one enclosed within the other.

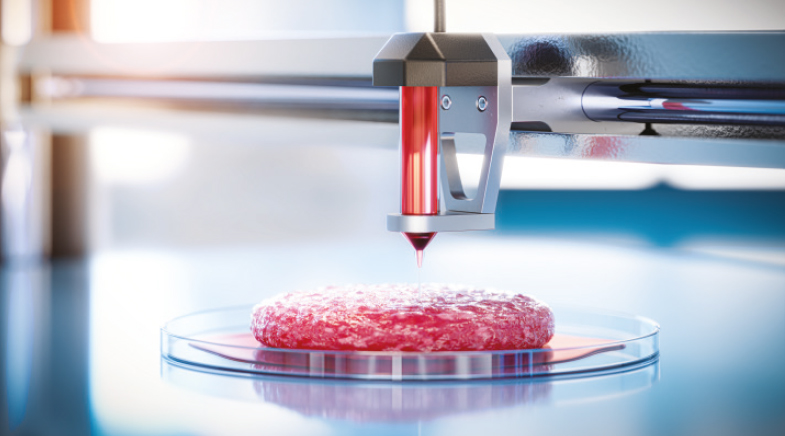

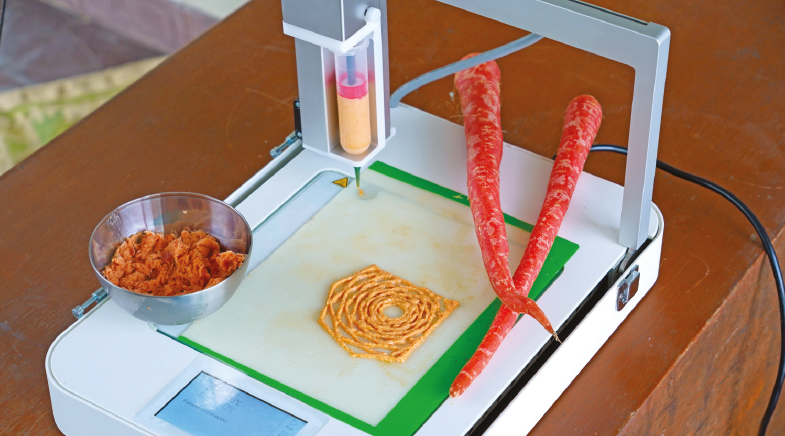

3DFP is a technology by which customised food items can be 'printed' layer by layer, as the nozzle releases the 'food ink' in a pre-programmed design. While there are many varieties of food printers, the most in use is the extrusion type, where the ink is pre-mixed and of a consistency that is extrudable through the nozzle. It cannot be as watery as dosa batter, because it will flow before the next layer can be printed on it. It cannot be of the consistency of chapati dough either, as that is not easily extrudable, says S. Thangalakshmi, Associate Professor in the Department of Food Engineering at NIFTEM-Kundli. Natively printable materials, like chocolate, hummus and peanut butter, are the easiest to work with, she says. A big chunk of ongoing research across the world aims to create newer food inks, making natively unprintable materials, like proteins and fibres, printable. This is done through various methods, like adding edible gums, hydrocolloids or oleogels.

Using 3D food printing technology, customised food items can be 'printed' layer by layer in a pre-programmed design.

In the past seven years, Indian researchers have experimented extensively with 3DFP. They created healthier snacking options like a fibre-fortified chicken lollypop for children (bit.ly/chicken-lollypop). They took discards from other food-processing streams and upscaled them into nutrition-packed snacks — noodles printed from an ink of potato peels, cookies made from the pomace of grapes after the juice was extracted, and protein bars from peanut protein cakes left after the extraction of oil (bit.ly/peanut-print).

"We even printed grains of rice fortified with iron," says Anandharamakrishnan, now the Director of the Thiruvananthapuram-based CSIR-National Institute for Interdisciplinary Science and Technology (NIIST). The process allows not just for the fortification of rice, but also for upgrading an inferior-quality rice, or broken bits, into a nutrition-packed product. The researchers have applied for a patent for this product.

ENTER AI AND ML

"In less than a decade, the thinking on 3DFP has evolved majorly. Take the example of optimising printing. We began testing inks through trial and error, then we moved over to using principles of rheology," says Jeyan A. Moses, Assistant Professor at NIFTEM-Thanjavur. Now, the researchers are making use of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) to optimise the process.

A research group at the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Mandi is working on applying these advanced methods to develop a matrix system to control the quality of printable food on four counts: texture, taste, colour, and calorific value. The team has developed a zero-calorie food ink with nanoparticles of functional foods and cellulose that can be used to make waffles or pancakes, and are now applying for a patent.

"We are working on personalising food," says Sumit Murab, Assistant Professor at the School of Biosciences & Bioengineering, IIT Mandi. A change in the ratio of ingredients in the ink (by giving those instructions to the printer) can alter the texture, and the user has the option of controlling the sweetness or savouriness. Additionally, the team is building an app that will recommend the ideal print based on the Basal Metabolic Rate and other physiological data of a person, he adds.

VISUAL DRAMA

3DFP came into being rather serendipitously two decades ago at robotics engineer Hod Lipson's Creative Machines Lab in Columbia University. His team was trying to figure out how to perform additive manufacturing with multiple materials (back then, 3D printing was restricted to a single material at a time), when it decided to work with easily available food materials like cookie dough, cheese and chocolate. In the process, the team realised the potential of printing food itself and by 2005, Lipson had created the first printer exclusively to print food.

Over time, the novelty of printable food was replaced in laboratories by discoveries of the uses 3DFP can be put to. It can change the shape and texture of foods, making them more attractive and palatable, especially for special groups. The Thanjavur team, for instance, had printed eggs in various geometric shapes, making them more appealing for children than the boring boiled ones (bit.ly/egg-print). At the Singapore University of Technology and Design, one group created a foodscape – hills and a boat on a plate – using pureed carrots, peas and bok choy as food inks. Such attractive makeovers are targeted at creating appetites for patients suffering from dysphagia and masticatory problems, for whom all meals are purees or porridges (bit.ly/foodscape-3D).

3D food printing can change the shape and texture of foods, making them more attractive and palatable, especially for special groups.

When Thangalakshmi developed her diabetes-friendly low-glycaemic index Mysore pak, she printed them in unconventional shapes like airplanes and flowers, to add to the visual appeal. "Eating is a process that is dependent on various stimuli – colour, texture, flavour. Food has to be aesthetically appealing, especially for groups that have trouble with food," says Anandharamakrishnan.

In fact, even as 3DFP technology gets further refined, research has already shifted to 4D printing, a process that involves the change of one parameter of the food, like shape or colour, post-printing. Think of pastas changing shape when boiled, a butterfly's folded wings opening up on adding hot milk to the breakfast cereal, or colour-changing idli. In India, researchers are experimenting with curcumin and anthocyanin in their inks for post-printing visual drama, as these pigments change colour on altering the pH (bit.ly/4D-colour). "Attractive presentations are a good way of delivering nutraceuticals, too," says Anandharamakrishnan. In fact, researchers believe that 3DFP might find commercial use in the nutraceutical sector sooner than in the food sector.

Making food healthier through 3DFP is another area of continuing research, where keeping a dish sweet without sugar or artificial sweeteners, or reducing the starch content, yet keeping the item high on satiety is a priority. One group of researchers recently created the sweet marzipan by replacing sugar with natural sweeteners that have a low-glycaemic index. The paper is under peer review.

While many of these products can be created through other mechanised processes, 3DFP scores in areas where a complex geometry is required. It is also a way to deliver fresh, on-demand food on site. "It is possible to compute the nutritional requirements of every child in a school and deliver to each student a personalised item, made on the spot, for a mid-day snack," says Moses. What such a delivery requires is the right ecosystem.

The trend of using plant-based proteins, specially to develop vegan meats, complements 3DFP technology, as the layering technique, along with multiple nozzle printers, is able to replicate more authentically the texture of a steak. An Israeli start-up, Redefine Meat, claims to use the technology for its range of plant-based meat products. In India, where faux meat preferences are low, plant proteins from ingredients like millets are usually converted into savoury snacks.

MISSING THE MARK(ET)

Laboratories across the globe are working on enhancing taste, making healthier options and more complicated structures using 3DFP. Last year, engineers at Columbia University printed a cheesecake with seven ingredients/inks, each in a different layer. But the tech is yet to catch up commercially. "Researchers are ready with the R&D. Across the world, around 300 food products have been printed; now the big breakthrough will happen when the industry is willing to invest in the technology," says Moses.

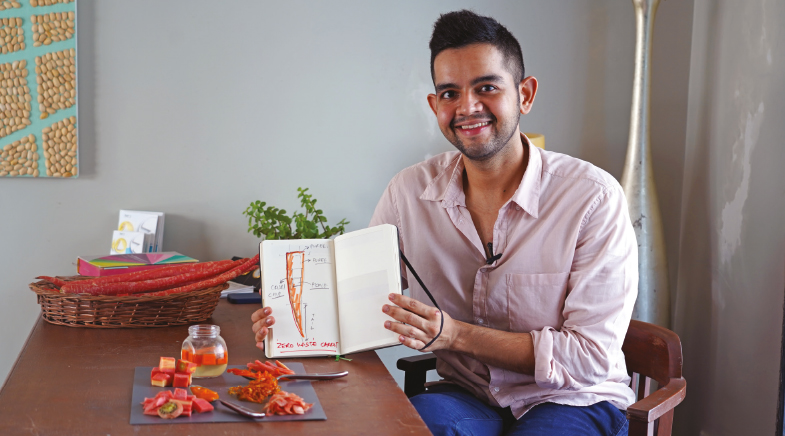

Most food printers are still being used in show cooking. Jashan Sippy, Founder of Sugar and Space and an architect by training, uses his food printer for demonstrations and shows. Often, he uses it in non-culinary events, like when he had to present his graduation project in college. "Mine were the only models which could be eaten after the exam," he recalls. During a project in the U.K. to introduce children of immigrants to the foods of their native lands, he created edible toys with lupin bean flour and alfa alfa.

The trend of using plant-based proteins complements 3D food printing technology, as the layering technique is more authentically able to replicate the texture of meat.

For Sippy, his printer is a versatile tool of the trade. At the catering college in Mumbai where he teaches, he created a project called Offaly Good to upscale brain, kidney, liver and other organs from the meat industry into delectable bites. 3DFP has so much potential, he says, but it is waiting for the right moment to take off.

There are various ways that 3DFP can go forward, say researchers. With multiple printers and bigger machines, the scale of production can increase to cater to larger orders of schools, hospitals or cafeterias. The Indian Council of Agricultural Research is keen to scale up 3DFP production to create newer products with traditional ingredients like jaggery and millets. "It has asked IIT Kharagpur to develop larger printers which can be installed in bakeries and cafeterias, in order to create a market for new products from traditional ingredients like millets and jaggery," says Jayeeta Mitra, Associate Professor at the institute's Agricultural and Food Engineering Department.

On the other hand, the 3DFP printer could become a household appliance, piggybacking on the shift towards personalised nutrition. "That breakthrough will happen only with a robust supply chain of food inks. At present, making your own mixes can get rather cumbersome, and defeats the purpose of automating cooking," says Benjamin Feltner, Chief Operations Officer of BeeHex Automation, a U.S.-based start-up. Its Founder, Anjan Contractor, had won a NASA grant with which he developed the technology to print a pizza from scratch. Contractor also worked with funding from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency and the U.S. Army to print personalised foods for soldiers on long deployments. However, with no contracts for orders coming from these routes, he decided to focus on the market that was available — the bakery and confectionery section. BeeHex specialises in designing custom-ordered printers for cake decorations, a process which speeds up the painstaking process of hand decorating, and yet, creates personalised products. It supplies to Europe, the Americas and Australia.

Most researchers remain positive that the breakthrough will come soon. There is so much interest in personalised food that sooner or later, people will want an option to create such foods at home. "I am looking at a future where a choice of items will be printable, on site, on demand. There will be a range of recipes ready by then for the machine," says Moses.

"Coffee machines only make coffee, but they got the right marketing. The future of 3DFP is as much about the technology as it is about its marketing," says Feltner.

See also:

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH