What’s cooking in the lab?

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 01 edition 02 :: Jul - Aug 2021

With cultivated meat, scientists give carnivores something to chew on while also preserving the environment.

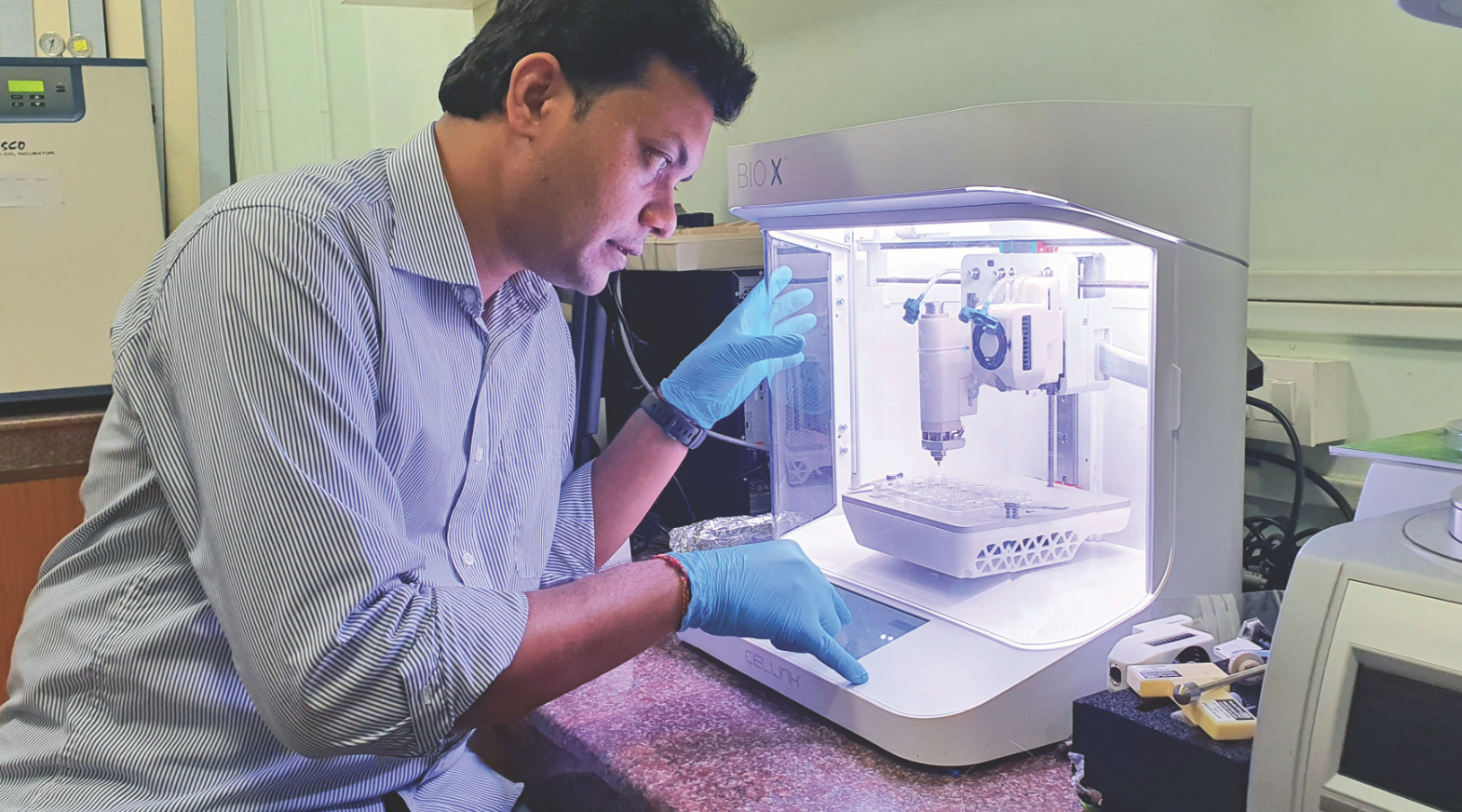

In 2011, when Biman B. Mandal set up his lab at the Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati (IITG), his plan was to grow cells, tissues, and organs to help patients with organ damage due to disease or injury. As the lab gained expertise in growing cells of different kinds, Mandal became interested in another type of cell culture: growing edible cells in the lab. In other words, cultivating meat. "We were already growing muscle cells in the lab, and meat is also made up of mostly muscle cells. It seemed obvious to give it a go," said Mandal, Professor in the Department of Biosciences and Bioengineering, IITG.

After pondering for a while on the type of edible cells to grow, Mandal and his colleagues zeroed in on chicken cells, since chicken is widely eaten across India. They extracted muscle progenitor cells from chickens and placed them in a nutrient medium in which the progenitor cells were able to divide and grow into muscle cells.

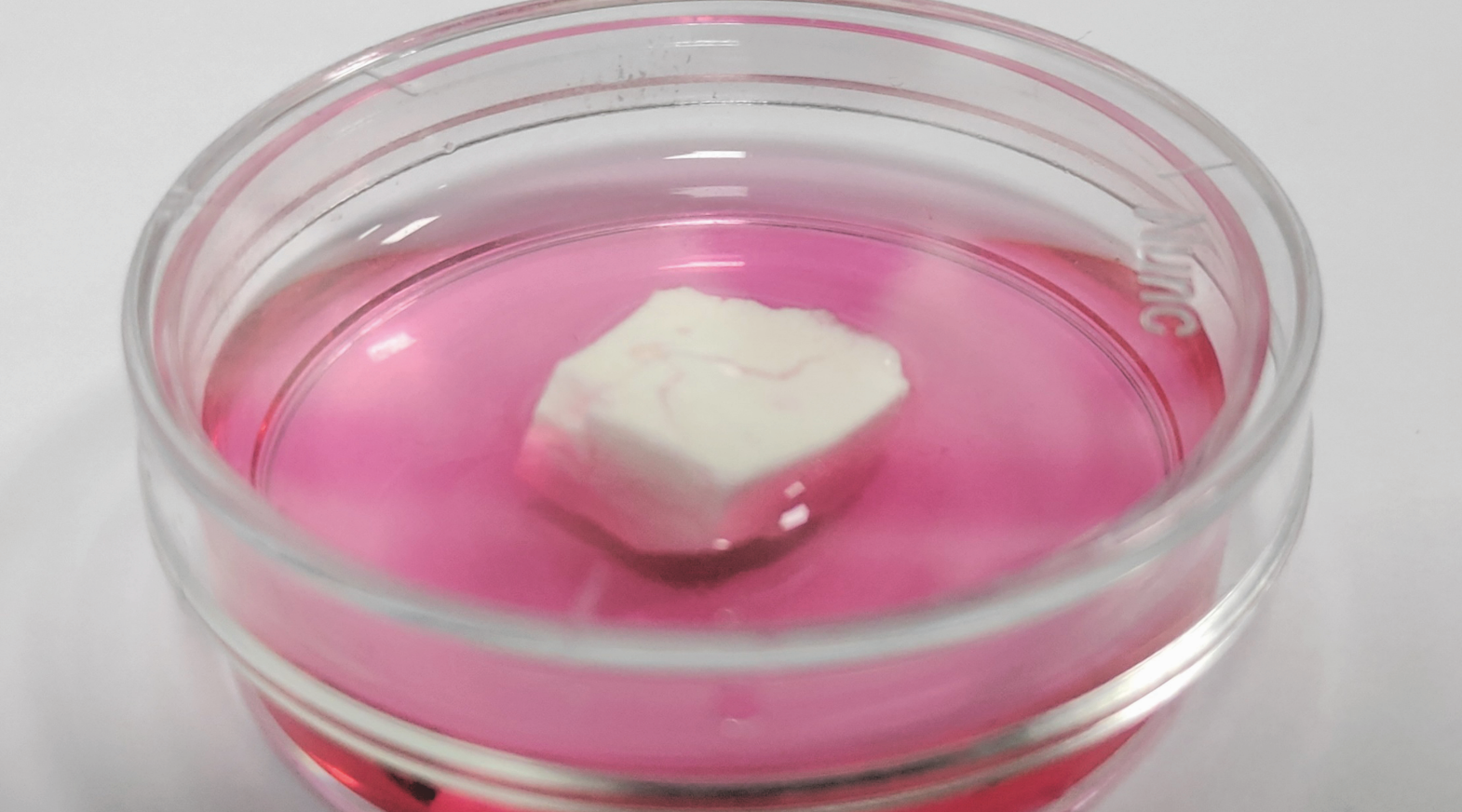

As simple as it may sound, this process required several iterations. For starters, the nutrient medium - food for cells - needed to be just right for cells' growth and to be free of components that are unpalatable to humans. They also needed to create a scaffold, or a structural material, on which the cells could grow. Again, the scaffold had to be made of edible materials. As the cells grew, they had to be protected from infections without using antibiotics.

Soldiering on, the IITG team was able to tackle the challenges that came its way and was able to grow chicken cells in its lab by 2019.

That same year, almost 2,000 km west of Guwahati, two Jawaharlal Nehru University-based researchers, Siddharth Manvati and Pawan Dhar, started up ClearMeat in New Delhi. ClearMeat had developed its own technology to grow chicken cells in the lab. The product, comparable to chicken keema (mince), also requires the right nutrient medium, a scaffold, and sterile conditions to grow, but it was developed independently. The underlying technologies are their trade secrets; for instance, Manvati and Mandal don't know what the other team's nutrient medium is composed of.

COST CONSIDERATIONS

However, what's common to the two teams is that they have both worked hard to develop a nutrient medium or cell-growth medium that is free of animal products like serum - and which is not expensive. The cost consideration is critical. In the long run, the cost of the growth medium will be a major determinant of the cost of meat cultivated in labs, which in turn will decide its commercial success on the supermarket shelves.

Cell culture - the science of growing cells in a lab - is a fairly old technique, and scientists use it routinely. It is, however, highly dependent on the use of foetal bovine serum (FBS) as a growth medium. Not only is FBS very expensive, it is not suited for growing chicken cells, for the reason that consumers may balk at eating chicken cells grown in calf serum. Which is why the researchers felt the need to grow their cultivated meat in newer types of growth medium.

"Even the most inexpensive serum-based growth medium in the market costs ₹1,500 for 500 ml," says Mandal. Against that, "our in-house growth medium costs only ₹50 for 500 ml, and is composed solely of cereals and edible products," he added.

The IITG team has patented its formulation and hopes to sell it to anyone interested in trying out a new growth medium for routine cell culture experiments. However, it may be a while before the formulation becomes available since the processes are still being worked out. Similarly, ClearMeat also has plans to take its growth medium, branded ClearX9TM, to the market.

As for the cultivated meat itself, the price will be an important factor that will determine its commercial success based on consumer acceptance. Manvati says ClearMeat’s chicken mince will be available at about ₹850-900 a kilogram, which he notes, is "comparable" to the price of processed chicken meat in the market, but will come down further with scale of production.

However, for cultivated meat to achieve price parity with regular chicken meat, which retails at about ₹200 per kg, will take at least 10 years, says Varun Deshpande, Managing Director of Good Food Institute India (GFI-India). GFI-India is a not-for-profit working to enable the smart protein industry in India, which includes cultivated meats, plant-based proteins, and fermented proteins.

THE ’TASTE TEST’

However, even more than the price, lab-cultivated meat will face another stern test of consumer acceptance: its taste and texture, and how close they are to natural meat. It is the proportion of muscle and fat in the meat that often determines the taste and texture. Researchers say they can modulate the amount of fat and muscle to suit consumers' requirements.

The more closely cultivated meat recreates the experience of eating regular meat, the more likely that consumers will place repeat orders for it.

In 2020, ClearMeat wanted to conduct a public tasting event for its chicken mince equivalent product but couldn't do it because of the COVID-19 pandemic. The company did, however, conduct a small private tasting event, where Manvati and some of his colleagues tasted the ClearMeat product. They cooked it at home with regular Indian spices and rice. "You could call the dish chicken keema rice," says Manvati. The taste, however, was not very close to that of regular meat – perhaps owing to the "lack of fat cells" in ClearMeat's chicken mince, he reckons. This experience led the team to make changes in its product to improve the taste and texture and get them closer to regular meat.

Even as researchers alter and improve their products to match the real thing, they wonder how well they will be accepted by the consumers.

Some studies have tried to assess this. For example, a 2019 survey of 1,024 urban Indian consumers by GFI-India found that:

• 56.3% of the participants were very or extremely likely to buy cultivated meat;

• 32.9% were somewhat or moderately likely to buy it; and

• 10.7% were not at all likely to buy it.

Additionally, increased familiarity with these foods tends to drive up the acceptance rate, so India is expected to have a big market for cultivated meat over time, says Deshpande.

CULTIVATED vs REGULAR MEAT

Many studies have made the case that cultivated meat and other forms of smart proteins are more environment-friendly and sustainable sources of protein than regular meat. Production of regular meat emits more greenhouse gases, requires more land and more water in comparison to cultivated meat.

A recent industry-based life cycle assessment (LCA) and techno-economic assessment (TEA) by GFI claimed that cultivated meat reduces the carbon footprint of beef, pork, and chicken by 92%, 52%, and 17%, respectively, when production facilities where cultivated meat is grown are powered by renewable energy. Cultivated meat also reduces land use up to 95% compared to beef, 72% compared to pork, and 63% compared to chicken, it claimed.

Another critical consideration is that the regular meat industry relies heavily on antibiotics to keep animals disease-free. This eventually contributes to antibiotic resistance. Cultivated meat, on the other hand, is grown in sterile conditions, so antibiotics are not required to keep infections away. Because of the sterile growth environment, chances of contamination are "very low" for cultivated meat, says Rama Tentu, research fellow at GFI-India. Additionally, the less-than-hygienic conditions in slaughter-houses and animal farms mean that "cultivated meat will always have a lesser microbial load than regular meat," she notes.

NEW PROTEIN SOURCES

As the global population increases, the demand for proteins is expected to rise. The 2012 edition of World Agriculture Towards 2030/2050, a report published by the Food and Agricultural Organization projected that global production and use of meat would rise from 258 million tonnes in 2005/2007 to 455 million tonnes in 2050. The global population is expected to rise to 9-11 billion people by 2050, which will lead to a commensurate rise in the demand for agricultural products.

A 2021 study in the Annual Review of Food Science and Technology journal points out that “a leap in traditional agricultural productivity is necessary to meet the rising demand” and that technologies like cultivated meat offer a “potential solution”.

India, where a large share of this growing population will reside, will require adequate proteins to nourish the large populace. Indian diets are typically deficient in proteins and the country is home to a huge number of malnourished children. Smart proteins like plant-based meats and cultivated meats will perhaps be able to compensate for this deficiency in the great Indian thali.

FROM LAB TO MARKET

The first ever cultivated meat burger was tasted at a public event in London in 2013. The meat for the burger was cultivated at Maastricht University, the Netherlands, by Mark Post (see box), a tissue engineering scientist. He has since launched Mosa Meat, a cultivated meat company.

The more closely cultivated meat recreates the experience of eating regular meat, the more likely that consumers will take to it.

From then onwards, the cultivated meat industry has expanded dramatically. Several companies across the globe are working on producing a variety of cultivated meats. For example, U.S.-based UPSIDE Foods is working on producing cultivated chicken, beef, and duck. U.S.-based BlueNalu and Singapore-based Shiok Meats are working on cultivated seafood. Dutch start-up Meatable is working on pork.

For some companies, the transition from lab to market has already begun. In December 2020, Singapore became the first country to allow the sale of cultivated meat. The Singapore Food Agency granted safety approval for "chicken bites" produced by Eat Just, a U.S.-based cultivated meat company.

SuperMeat, an Israel-based food tech company, is conducting public tasting events for its cultivated chicken.

THE INDIAN REALITY

In India, however, the cultivated meat industry is still at a nascent stage. Its success depends not only on how much funding the early movers in the industry are able to attract but also on the emergence of an ecosystem that helps this industry thrive. There is a felt need for a focus on training and on nurturing talent in this industry - and for support to be made available to start-ups making products or platforms that make it possible to grow cultivated meat at scale. One example of such a start-up in India is the IIT Bombay-based Myoworks, which makes scaffolds on which cultivated meat can be grown in labs.

Industry players feel the need for sustained government support in the form of grants and also clearly laid-out regulatory guidelines. As the industry is still developing, it is perhaps only to be expected that the regulatory guidelines will evolve with time, but the authorities shaping these regulatory frameworks should ensure that cultivated meat "is subjected to the same checks and tests for safety as the regular meat," says Deshpande. Also, "safety testing methods should be developed using the latest scientific knowhow," he adds.

Strikingly, the COVID-19 pandemic has forced many meat-eaters to re-evaluate their food choices and opt for animal-free food products. The regular meat industry is going through a churn and is additionally battered by diseases like avian flu and swine flu. Not enough is as yet known about how all this will affect consumer behaviour in the long run, but cultivated meat industry players clearly see it as an opportunity for them to step up with an alternative.

"The long-term prognosis for the smart protein sector remains hugely positive," says Deshpande. "It offers a means of resilience even to legacy animal meat producers who may want to future-proof their business." Now that’s a meaty proposition that producers will find hard to pass up on.

The future of meat

- Cultivated meat made it to the culinary mainstream in 2013, when a 'beef' hamburger made from cow muscle grown in a laboratory was fried – and eaten – at an event in London to showcase "the future of food".

- The tissue cells had been cultivated in a laboratory by Dr Mark Post, a tissue engineering scientist at Maastricht University.

- The burger didn't exactly pass the 'taste test' with flying colours: a few of those who sampled it said it was a little pale, and lacked in juiciness and seasoning.

- Others, however, gave it full marks for "mouth feel".

- The project cost – an estimated $325,000, which made it the world's priciest burger! – was bankrolled by Google co-founder Sergey Brin.

- Brin was evidently motivated to back the project owing to concerns about the sustainability of meat production and animal welfare.

- Funding for start-ups in the cultivated meat space has increased substantially since 2013. According to a 2020 report published in the Trends in Biotechnology journal, from 2015 until early 2020, the amount of publicly disclosed capital invested in cultivated meat companies touched about $320 million.

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH