An empowering eye-opener

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 01 issue 06 :: Nov - Dec 2022

A neat gadget seeks to help the visually impaired aim high.

Manjula M. is one of India's 9.2 million visually impaired people. She is also in the tiny 1% blind population segment in the country that is literate — or more specifically, braille literate.

She lost her eyesight at the age of six. Now 26, she works for the not-for-profit National Institute for Smart Government. But it wasn't easy for her to come this far.

For the visually impaired, even the simple things of life are complex hurdles. But nothing perhaps is as damaging as not being able to pursue higher studies for a better future.

What makes higher education inaccessible is the unavailability of braille books. Manjula used to rely on her computer to listen to e-books with screen readers — software programs that read what's on the screen — and text-to-speech (TTS) engines, which turn text into audios. The bigger challenge, however, was printed books. She had to scan them first, convert images into text, and then use TTS to listen to them.

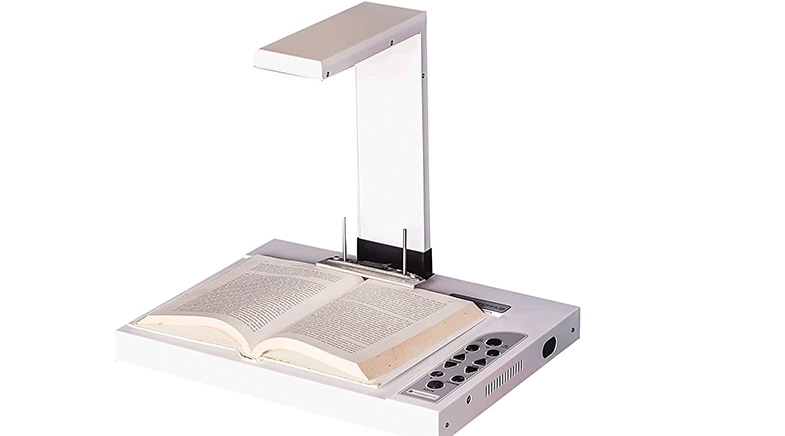

Earlier this year, she came across URead. An A4-plus-sized flat machine with a camera arm, the gadget can read books in eight Indian languages, apart from English and Hindi, without an internet connection. It creates a back-up in text and audio files that users can take away. In a special study mode, it lets users go back and forth over a particular line and even spell the words.

For Manjula, who dreams of appearing for the civil services exam, it has made studying far easier and accessible.

AN IDEA IS BORN

URead was created by IIT Kanpur alumni Vinod P. Deshmukh and Padmanabhan S.N., who spent over three decades together working in research and development (R&D) for Wipro and Mindtree.

In 2012, the duo, then in their early 50s, left Mindtree, where Deshmukh was President & CEO, R&D Services, and Padmanabhan, senior VP in the same unit.

They founded InnovationHub in 2013 to leverage technology for the disability sector. Deshmukh credits the decision to the corporate culture at Wipro as well as Mindtree, which encouraged technologists to take up social service, and where they were both closely involved in educating and sponsoring children with cerebral palsy.

They began their journey with the visually impaired segment after discovering it lacked research and social support.

"Initially, we wanted to create a navigation system similar to GPS for the visually impaired, one that would work indoors," Deshmukh recalls, in his office in Bengaluru. "But we decided to try the concept with Ausion, our first product."

It took almost four years and "tens of lakhs" of their own money for Deshmukh and Padmanabhan to develop URead, which they released in January 2022.

Ausion — which refers to audio vision — is a handheld device, like a torch. It gives the visually impaired a sense of direction and accurately detects obstacles up to three metres using a 14-alphabet musical language. However, it was quite difficult to train people to use it, even with a training lab.

Four years later, after giving away 3,000 units through corporate sponsorships, they figured that mobility might not be the way to make the visually impaired self-reliant. "When we started, we thought freedom to move around was most important to the visually impaired," Deshmukh says. "But we discovered it wasn't when compared to learning things that would help them get a job."

That's when they started exploring education.

The visually impaired, he adds, learn through braille, which takes six months to a year to master. "There are limited braille teachers and braille literature is also limited, apart from being expensive." Technology helped in the reading of books, but people still had to take others' assistance, click hundreds of page images, and use multiple apps to listen to the text. The two decided to build something that was easy to use, affordable, tailored for the Indian market, and could make the visually impaired self-reliant, Deshmukh adds. "Hence, URead."

INNOVATION, ITERATION

URead essentially stitches together open-source programs that help the visually impaired read, and customises them to make reading easy and accurate.

The device has a flat rectangular space to keep a book, a book-holder, a camera to scan, audio jacks and a keyboard to control the navigation. Users can recognise the keys with their different shapes and sizes and convex and concave surfaces.

URead guides users step by step through an audio menu. Once a book or a document is placed on it, it takes an image of the page and processes it using a proprietary algorithm. The processed image is converted into a text document with Tesseract, an optical character recognition (OCR) software. URead does language processing on the text before it goes through a TTS program.

Deshmukh adds that URead takes care of punctuations that many speech engines ignore, and adjusts the speed depending on the language. URead's algorithms are also designed to make the output audio sound closer to the human way of interaction.

The device supports up to three users at a time and saves everything it reads in separate text and audio files, for each user, across multiple sessions, till the time they take a back-up or choose to cancel it.

"You need a lot of nuts and bolts to put all these engines together to make a complete machine," Deshmukh says. "Technology goes into making it simple."

The two decided to build something that was easy to use, affordable, tailored for the Indian market, and could make the visually impaired self-reliant.

The machine has four sub-assemblies, two of which were designed in-house, to control different parts, and 16 GB of internal memory. It runs on a quad-core processor.

"Most open-source systems are meant for a single core. But here we have tweaked them to run on four cores to utilise the full processing power," Deshmukh says. "That's the special sauce that we add."

This makes URead three times faster than open-source software to run on a computer. URead takes 30-40 seconds to process the first page, and while it reads it, the rest of the pages get processed in the background.

GLOBAL INITIATIVES

It took almost four years and "tens of lakhs" of their own money for Deshmukh and Padmanabhan to develop URead, which they released in January 2022.

According to the International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness, India has 230 million people with vision loss, including the visually impaired. There are, however, no products similar to URead in the country. Deshmukh believes that people don't see a huge business potential in it, and a project like this requires a long gestation period for social investors to be interested.

A few research papers on smart readers for the visually impaired — published by Indian students in journals including the International Journal of Information Technology and the International Journal of Engineering Research & Technology — deal with installing OCR and TTS software in Raspberry Pi — small, single-board computers — to create a portable device that can read any printed text in real time. However, none of these has turned into a commercial product yet in India.

Globally, a few companies have developed smart readers. For instance, U.S.-headquartered Enhanced Vision has a product similar to URead to read magazines and newspapers. Israel-based multinational OrCam offers small portable devices that assist users in reading printed or digital text on the go. Another similar product is FingerReader, a wearable ring-like device developed by MIT Media Lab that enables visually impaired people to read text printed on paper or electronic devices.

Deshmukh believes that these are innovative technologies but unsuitable for India as they don't cater to regional languages, apart from being expensive. He is exploring partnerships with corporate houses, colleges, public libraries and eye hospitals to make URead widely available, so that the device — priced at ₹30,000 — remains free for users.

For Deshmukh and Padmanabhan — who have been taking an annual salary of one rupee for the past nine years — URead is not a means to make money. They intend to bring its price down with scale, but Deshmukh says that may take another two or three years.

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH