A high five

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 05 issue 01 :: Jan 2026

The search for a fifth fundamental force is gathering momentum.

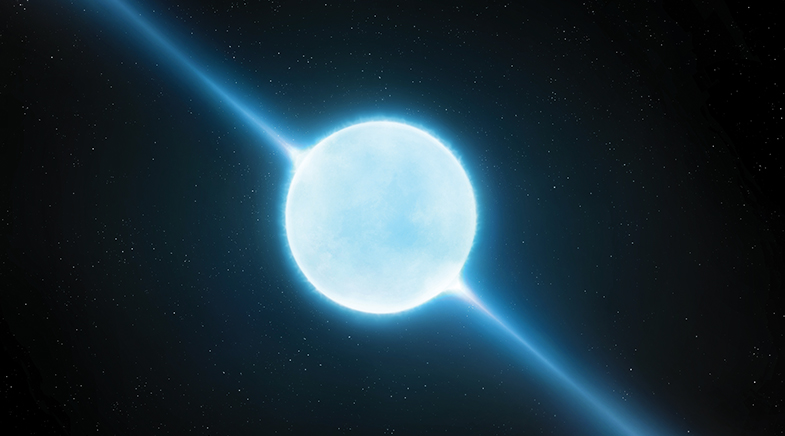

Their quest began in early 2025, when astroparticle physicist Edoardo Vitagliano discussed an idea that was taking shape in his mind with his collaborator, Damiano F.G. Fiorillo. Vitagliano, who teaches at the University of Padova, Italy, wondered if a neutron star, the extremely dense core of a massive star that exploded as a supernova, could be the starting point in the search for a new fundamental force — the so-called fifth force. The idea resonated with Fiorillo, and Vitagliano started a search with his students for this force, which they hoped would lend a new dimension to the established set of four forces.

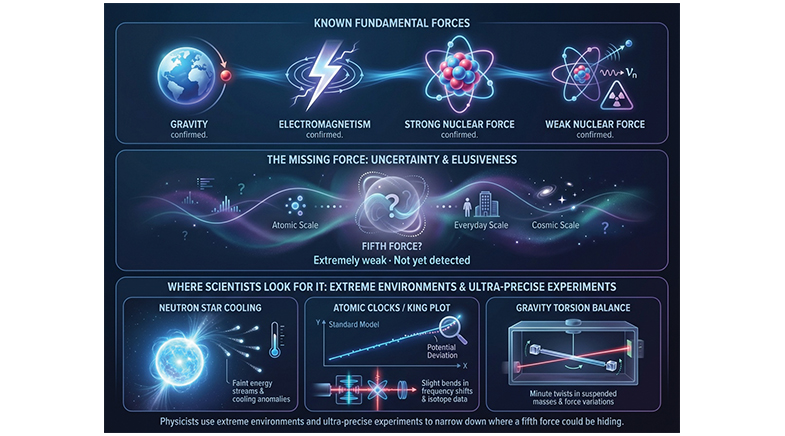

The four forces — gravity, electromagnetism, strong nuclear force, and weak nuclear force — govern most natural phenomena. But these four forces fail to explain some of the universe's mysteries, such as dark matter, the nature of gravity and dark energy. "From an anthropic point of view, all four interactions are necessary for human life, and the universe would look very different if any one of them were missing," Vitagliano says. But he indicates that these four forces may not tell the whole story.

Physicists have long wondered about an unknown force that could answer unsolved questions. To test their theory, Vitagliano's team focused on neutron stars to examine how they cool. If a fifth force existed and was carried by new, light particles, these particles could be produced inside a star and escape, carrying energy. This would make the neutron star cool faster than expected.

A recently published study (bit.ly/Neutronstar-cooling) by Vitagliano, Fiorillo and others shows that while gravity and electromagnetism act over long ranges and the weak nuclear interaction occurs over subatomic distances, there could be a middle ground: distances thinner than a human hair but larger than an atom. This is called the mesoscopic scale. If a fifth force exists with a range in this regime and is mediated by new scalar particles, it could significantly affect the understanding of the universe. Scalar particles are hypothetical particles that carry a new kind of force and affect other particles equally in all directions.

"If such particles exist, they could act as force carriers," says Vitagliano. He adds that they could also be produced in the hot, dense environments of stars. Because the fifth force would be exceedingly weak, extreme conditions and a large number of particle interactions are needed to produce measurable effects.

The paper reveals that old, cooling neutron stars are surprisingly powerful places to search for this hidden force. A neutron star continues to lose heat slowly, even thousands of years after its birth. If a new particle exists and interacts with neutrons, it would give the neutron star an extra way to lose energy.

They found nothing unusual — and that was significant. Because neutron stars are so dense and cold, they would be especially sensitive to scalar particles. The study shows that cold neutron stars can rule out scalar forces up to a million times more strongly than earlier supposed, across a wide range of minuscule distances. By not seeing neutron stars cool too fast, the authors set the strongest limits yet on a possible fifth force acting between ordinary matter.

PRECISION IS KEY

"At extreme precision, even atoms begin to reveal effects that physics once thought were negligible," says Piet O. Schmidt, a physicist at the Institute for Experimental Quantum Metrology (QUEST), Leibniz University Hannover. Even a tiny deviation could signal new physics. This idea motivated the development of ultra-precise atomic clocks; in 2007, Schmidt joined a team working to build some of the most accurate timekeeping devices ever made. In 2011, researchers realised that such precision could turn clocks into powerful tools for testing the basic laws of physics. Their initial focus was to search for tiny changes in fundamental constants, such as the fine-structure constant, which determines the strength of the electromagnetic force. In 2017, theorists proposed a tabletop experiment using what is known as the King plot tool to search for a possible fifth force of nature.

A team designed an experiment to measure gravity at small distances. They found that gravity behaved exactly as expected.

In their recently published findings (bit.ly/King-Plot), the researchers focused on calcium atoms. Calcium atoms come in different versions, called isotopes, that differ only in the number of neutrons they have. These tiny differences cause minimal changes in the energy levels of the atom's electrons. Physicists measure these tiny changes across different calcium isotopes and then plot the results against one another in the King plot graph. "Usually, the graph is a straight line, but if a new, unknown force is acting between electrons and neutrons, that straight line bends or breaks. Any deviation, however small, is a clue," Schmidt explains.

The team found something striking: the points no longer lay on a straight line. The deviation was real and far too large to be explained by measurement error alone. At first glance, this deviation could be a hint of a new force acting between electrons and neutrons. But other possibilities couldn't be ruled out. "Not finding a new force is still progress: it sharply narrows where such a force could be hiding," says Schmidt.

The experiment raised the bar for future searches. It showed that atomic experiments are now sensitive enough to probe physics at a level where previously neglected nuclear effects start to matter. Schmidt thinks tabletop atomic experiments are now powerful enough to challenge ideas once reserved for giant particle colliders.

In India, C.S. Unnikrishnan, a physicist at the Defence Institute of Advanced Technology in Pune, designed the country's first experiment to detect the fifth force in gravity in the late 1980s. "What we loosely call a 'fifth force' is often a force of the gaps. It's usually proposed to fix one stubborn anomaly, not to explain nature more broadly," he says.

Unnikrishnan spent more than three decades on one question: Einstein built relativity on the equivalence principle, but physics never answered where it came from. "That missing explanation is what drew me in," he says. The equivalence principle says everything falls at the same rate, no matter what it is made of.

Unnikrishnan and his collaborators tested this idea with precision, using a sensitive instrument called a torsion balance. Instead of dropping objects, the experiment compares how different materials respond to gravity while suspended in a delicate balance. If gravity acts in the same way on all materials, the balance stays perfectly still. But if there were a fifth force, it might act slightly differently on different materials, depending on their composition. That tiny difference would cause the balance to twist ever so slightly. The experiment didn't find any evidence of the fifth force, but it closed many doors, sharpening the search for future experiments. "The precision gravity experiments mattered not just scientifically; they built the confidence that made later projects like the gravitational-wave detector (LIGO-India) possible," he says.

The torsion balance was also used by researchers at the University of Washington, U.S. They designed an experiment to measure gravity at extraordinarily small distances. Two carefully shaped metal objects were placed very close to each other, as near as 52 micrometres, and one of them was slowly rotated. If gravity behaved differently from what Newton's law predicts, the twisting motion would reveal it (bit.ly/Gravity-torsion). Gravity is incredibly weak at such short distances, and many other effects — such as electrical charges, magnetism, vibrations, or even dust — can easily overwhelm the signal. The team spent years refining their set-up, shielding it from outside disturbances, and carefully accounting for every possible source of error. They found that gravity behaved exactly as expected, even at these tiny distances. Although the experiment did not discover a new force, it ruled out a large class of theories that predict new gravitational effects at short distances. It also set the strongest laboratory limits yet on how strong or long-ranged any unknown force related to gravity could be.

These experiments help scientists understand the setting for the elusive force by ruling out where new physics can hide. Each closed door leads to the possibility of an open one.

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH