In Kashmir, these fossils reveal a butchery

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 03 issue 10 :: Nov 2024

Elephant fossils unearthed in Kashmir yield a grim story, and insights into humans' ancestors from the Middle Pleistocene age.

It was August 2000. A group of geology students from the Government Degree College, Sopore, in Jammu and Kashmir was on a college study trip. At Pampore, on the outskirts of Srinagar, Fayaz Ahmed saw an outcrop exhibiting soil layers of sand and clay, near an excavation site to lay a railway line to connect the Kashmir Valley to the rest of the country. The team decided to stop there for a while to study the fluvio-lacustrine sediments.

The team tried dislodging what the teachers thought was a fossilised log, but soon realised that it was big and probably archaeologically significant. They called Ghulam M. Bhat, then Reader in the Department of Geology and Geophysics, University of Kashmir, Srinagar. Bhat drove to the site and recognised the protuberance as part of a fossilised elephant tusk. Fossilised elephant remains are known to have been recovered in the area; a Yale University expedition in the 1930s had unearthed elephant fossils remains from nearby Sambora village.

Bhat put together a team, which began excavating on August 31. On September 6, they exposed a huge skull, 4x5 feet, with two broken tusks. One was a foot long, the other 3 feet long. The team recovered six rib bone pieces, the antlers of a deer, and one flint piece and stone tools. "It was a tiny piece," says Bhat about the flint, "and I actually threw it away as irrelevant to this dig, not realising that this flake could tell its own amazing story."

Later they unearthed 87 stone tools, big and small. The smaller chips of stone tools fitted neatly into the grooves left on the bigger stones, indicating that the stone tools had been made at the site itself, by chipping larger pieces of rock procured from a nearby site into sharp and serrated edges for cutting the flesh. Other tools indicated they were used for smashing bones to access marrow (bit.ly/butchery-India). Researchers see the animal fossils and tool remnants as the earliest evidence of animal butchery in the Indian subcontinent (bit.ly/florida-fossils). Nowhere else in the region have the two been recovered from the same site.

It would be two decades before these discoveries would be formally revealed to science as dating back to the Middle Pleistocene age. Bhat returned to the University of Jammu after covering the fossils at the site itself. Another seven years would pass before the crates were moved to a corridor in the University of Jammu. These crates remained there for a few more years, before they were finally displayed at the Wadia Museum of Natural History in the university campus, where they are now housed.

Bhat was not satisfied. The fossils had a home, but they needed a name and an identity. As a sedimentologist, he didn't understand the language of the fossilised bones. Given the inter-university claims and counter-claims on the specimens, other archaeologists were not keen to work with the fossils. He sent pictures to some experts, and they felt it was most likely Palaeoloxodon namadicus, a species that once roamed in peninsular India. How had that species crossed the Pir Panjal Range? "I wanted experts see the specimen, not its pictures," he says.

In 2019, the British Museum funded a team of researchers in ancient butchery, stone tool analysis, taxonomy, and amino acid age determination. They spent a week measuring and studying the skull and other fragments. The skull of this specimen, almost intact, was very similar to that of Palaeoloxodon antiquus (an extinct elephant species that inhabited Europe and western Asia) with one difference: it lacked a prominent crest at the back of the skull for attachment of the huge muscles.

Only one other skull of this type had been discovered, in Turkmenistan, and it is now in a museum in St Petersburg. Scientists had treated it as an aberration and not a distinct species. The intact Pampore skull, however, made it clear that these two did indeed represent a distinct species, Palaeoloxodon turkmenicus, which roamed in the region between 300,000 and 400,000 years ago. Among the largest of the elephants to roam the Earth, an adult P. turkmenicus stood four metres tall at the shoulders and could weigh up to 14 tonnes. "The Pampore Palaeoloxodon could easily rest its chin on the biggest bull Asian elephant of today," says Steven Zhang, a vertebrate palaeontologist at the University of Helsinki and a co-author of a recently published paper (bit.ly/Pampore-elephant).

Zhang has done comparative studies on fossils of extinct elephants from across museums in Europe, East Africa, Asia and the U.S. Though he was not part of the team that visited Jammu, his analysis of the specimen contributed to the identification of the specimen. "The Pampore elephant skull adds to our knowledge of a potential missing link in the understanding of Palaeoloxodon evolution," says Zhang. Palaeoloxodon are colloquially called 'straight-tusked' elephants and are among the largest land mammals to ever walk on Earth. They originated in Africa, and the fossils from there do not show a prominently developed skull crest. "The Pampore skull is, in most other ways, like in dentition, similar to P. namadicus from central India. But in a few details such as the shape of the massive tusk sockets, and lacking a bony depression on the eye socket seen in P. namadicus, it is somewhat more similar to the European species P. antiquus," he says.

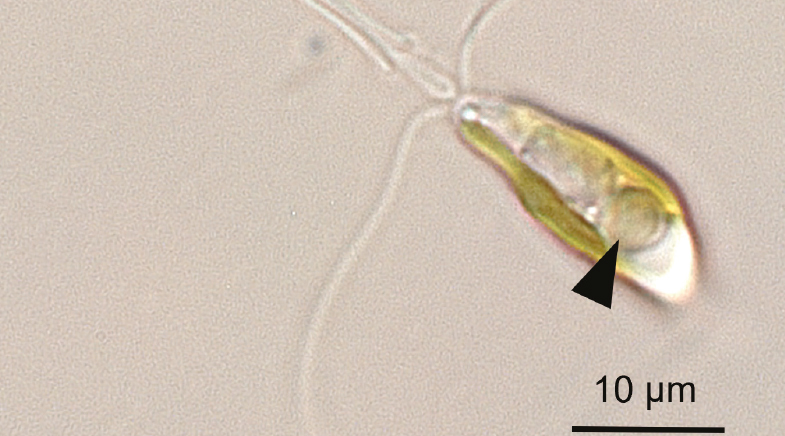

While the woolly mammoth is the most famous ancient tusker, Zhang says there were at least 40 species of elephants that have gone extinct. Six of these species lived in Asia. Today, there are only three elephant species left, the African forest elephant (Loxodonta cyclotis), the African savannah elephant (Loxodonta africana) and the Asian elephant (Elephas maximus). Complete elephant skulls are rare to find, because they are filled with air sacs to reduce weight. Most are identifiable from the teeth, but P. antiquus, P. namadicus and P. turkmenicus are exceedingly difficult to tell apart from just dentition. "That is why near-complete skulls like the one from Pampore are important," he explains.

Researchers see the animal fossils and tool remnants as the earliest evidence of animal butchery in the Indian subcontinent.

"We have actually confirmed that the remains belong to three elephants, one of which was a juvenile," says Advait Jukar, curator at the Florida Museum of Natural History and one of the investigators. Analysing the shape, deformities and density of the skull bones, the researchers conclude that the adult male (whose skull was found) was in its prime, but was suffering from sinusitis, which may have weakened it. Sinusitis is a common infection in elephants, given their extensive sinus cavities. Were the elephants, which were in a bog, hunted before butchering, or were they already dead?

"We cannot say whether they were hunted or scavenged, we only have evidence of butchery," says Jukar. The evidence of butchery came from three observations: bone shards show signs of impact; finding tools and skeleton in the same sediment; finding core and flakes at the same site, which formed the best confirmation that the stones were brought from elsewhere but prepared for the cutting at the spot. "Hominins did this a lot," says Jukar.

Vivesh Kapur, a vertebrate palaeontologist at the Birbal Sahni Institute of Palaeosciences, Lucknow, who was not part of the research, notes that the evidence of butchery is a rare find. He adds that finding older records of the species from Asia and the subcontinent "are warranted to fully comprehend the evolutionary history and the geographic distribution of Palaeoloxodon".

For Bhat, now 66 years old, it has been a long wait to get the Pampore fossils their due. In fact, even after the experts' visit in 2019, the COVID-19 pandemic further delayed their work, and it was only in October 2024 that the two papers were published. "My aim was to bring the enormity of the find to the world, and to get the site recognised."

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH