A Kerala village shows the way

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 01 edition 01 :: May - Jun 2021

Harnessing technology, and drawing on enlightened ecological policies, Meenangadi is on the path to becoming India’s first carbon-neutral village.

IN THE faint light of January, there’s a quaint twinkle in Madhavan P.K.’s eyes, but it masks a deep concern. As the 83-year-old coffee farmer glides through his farmland of less than an acre in Meenangadi village in Kerala’s Wayanad district, he caresses a pretty unusual coffee bush: it has both unharvested beans and white flowers. “Normally, the beans from the plant would all have been harvested before the flowering season begins,” he says. “But it’s all changed now: winter is arriving later than before, and is rushing prematurely into spring.”

That seasonal shift has had serious economic consequences for Madhavan. Over the past decade, the coffee yield from his farm has fallen to a third. “It’s the climate,” he explains. “It’s either too hot or too cold these days.”

For countless farmers like Madhavan, the ravages of climate change impose real-world costs. Most of Meenangadi’s 30,000 residents are subsistence farmers: they grow crops and raise livestock for their own use. But they are at the mercy of everyone from rain gods to politicians.

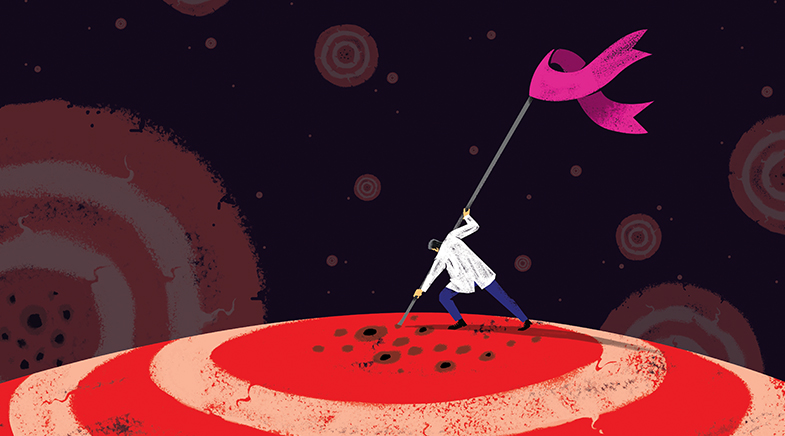

Yet, Meenangadi, a foggy hill station in arguably one of the greenest places in Kerala, has set itself an ambitious goal: to reverse the impact of climate change by becoming India’s first carbon-neutral village by 2027. And it is halfway towards getting there by harnessing an unusual experiment, which has put it on the global ecological map.

India is the third-largest emitter of greenhouse gases, behind the United States and China (excluding the European Union as a single block). A decade of rapid economic growth, which transformed villages into urban metropolises, is largely to blame, according a study published last year in Economic and Political Weekly. India’s capacity to bend the arc of those emissions will hinge on the future of Indian cities as well as its villages. And if Meenangadi’s ecological experiment succeeds, it could serve as a model for how greenhouse gas emissions can be reduced without compromising on development.

HOW THE JOURNEY BEGAN

The village’s journey on the low carbon path began quite by chance. In 2015, developmental economist Thomas Isaac presented a paper at the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Paris. Representatives from Thanal, a non-profit organisation that works on environmental projects in Kerala, attended the session. Inspired by the conference proceedings, they envisioned a carbon-neutral village in Kerala.

That thought experiment acquired life in 2016, when a Communist Party of India (Marxist)-led government came to power in Kerala, and Isaac became Finance Minister.

Wayanad, being small and climate-sensitive, was seen as the best place for the pilot scheme. Meenangadi panchayat was chosen since the CPI (M) had an overwhelming majority there, and it was easier to get things going.

But as Isaac points out, the plans expand way beyond just that one village. “Once the pilot project (at Meenangadi) is on track, we want to expand it across all of Wayanad district,” he said. Nor is this campaign motivated by just feel-good idealism. “We want to brand the coffee from Wayanad as coming from a carbon-neutral place and provide a better return for farmers.”

It is impossible for a village to have zero carbon emissions. However, villages can reduce their carbon footprint, and offset their emissions – by planting trees, for instance. But almost five years in, Meenangadi’s ‘climate science’ experiment shows that building a carbon-neutral future is more a political challenge than a technological one.

For a start, no data about emission levels was available, said Ajit Tomy, who quit his engineering job to head Thanal’s data collection exercise in Meenangadi. With the help of hundreds of student volunteers, Thanal extracted and analysed data from various official departments to estimate the total emissions, he said.

“For example, we would get data on energy consumption (which contributes to indirect emissions) from the State electricity board,” he said. But only a sample house survey could establish the extent of emission from firewood burning for domestic cooking (which contributes to direct emission). Similarly, estimating the amount of carbon sequestered required data on tree population; in its absence, Thanal had to count the trees in every home.

These data sets were codified in a 2017 report. It estimated the total emission of GHGs (Green- House Gases) in Meenangadi for 2016-17 at 33,375 CO2eq (carbon dioxide equivalent, a unit that measures the environment impact of one tonne of GHG in comparison to the impact of one tonne of carbon dioxide). The transport and energy sectors contributed the most (45% and 39%, respectively), followed by waste management, agriculture and forestry sectors.

Next came the ‘carbon balancing’ part, which involved getting people to change their habits to pollute less and plant more trees. The local government sought to make coffee farmers aware of the crop losses they would face from an increase in temperatures, by an estimated 2-4 degrees over 25 years. It also streamlined sectors within its direct influence, such as waste management.

‘Zero waste and Zero Emission’ is one of the pillars of the Meenangadi project. Although waste accounts for only 3% of village emissions, the administration reckoned there was scope for reducing this almost entirely. The results are already showing up: once-ubiquitous plastic covers have nearly disappeared, villagers say. Garbage burning is penalised; the waste is segregated and collected at a common facility, from where the reusable waste goes into making manure, and plastic waste is used in road construction.

“This whole place was once a filthy dumpyard,” said Paulson P.A., who has been driving the village’s waste truck for 24 years. “Some households unwilling to pay to have their garbage taken away would burn it. But now, we have more waste than we can process.”

MONEY GROWS ON TREES!

Meenangadi’s most ambitious, and arguably the most daunting, target is elsewhere: to plant five lakh trees, the number required (in experts’ reckoning) to cancel out current emission rates. To secure villagers’ support for this initiative, Isaac and his colleagues developed a financial instrument, locally known as ‘tree bank’: farmers are given interest-free loans of `50 a year for every tree they plant. Only after a minimum of three years of tree-planting can farmers avail of the loan. And the loan needs to be repaid only when the trees are cut, which is an incentive not to cut them in the short term.

The saplings to be planted are chosen for their environmental suitability, and geo-tagged by a state-run nursery. Some are planted in public places; for instance, 38 acres of barren land belonging to an old village temple has been reforested. Others are chosen for their commercial utility for farmers so that when the tree is eventually cut, the proceeds from the timber sale can more than repay the loan.

There was one problem, though: financial regulation in India does not cover loans against trees. But villagers found a work-around business model. They created an escrow mechanism using a `10-crore budgetary support that Isaac provided. The money was deposited in a Fixed Deposit with a local cooperative bank, which is typically run by grassroots leaders. The ‘tree bank’ loans are disbursed from the FD interest.

This model gives farmers an incentive to let the trees survive for years, which allows the carbon to be sequestered for longer periods in the tree as well as in the soil biomass. Esablishing a cash flow from the trees also ensure that villagers are not forced to bear the burden of opportunity cost on their upkeep.

THE WAYANAD MODEL

Across the State border, in Kodagu, Karnataka, a contrasting scenario presents itself. Kodagu is contiguous with Wayanad, and both places have a similar ecosystem. Kodagu’s coffee estates are rich in biodiversity, just like in Wayanad, and service a number of ecosystems such as bird species and microclimate. But in Kodagu, the protection mechanism works by a top-down legal approach.

There, trees belong to the government, and are protected by law: the estate owners are not allowed to cut them. However, coffee estate owners often find themselves spending on labour to maintain the shade cover for their coffee plants. Over the decades, since farmers are not incentivised to “protect” the trees, they have moved to monoculture plantations of silver oak, a recent study from Bengaluru-based Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (ATREE) established.

Silver oaks have the kind of tree planks that allow coffee plants to grow in the shade. Lopping off the extra branches to maintain the right ‘shape’ does not entail excessive labour costs. And silver oaks have good timber value when they are cut, which gives farmers an alternative source of income. However, the study noted, silver oaks are less welcoming to biodiversity. Similarly, in northern Karnataka, farmers have taken to growing eucalyptus: they can sell the timber for paper. But the trees suck up an extraordinary amount of groundwater.

In Wayanad, however, the farmers not only have a personal incentive to grow the trees, but the trees have been well chosen by the State government so that they are aligned with the social and environmental benefits for the area.

The success of the Wayanad model lies in its fusing of environmental goals with behavioural economics. The government is not explicitly telling people what to do, but is nudging them towards an optimal choice. One downside, though, of such a strategy is that there is little to stop farmers from cutting the trees if they are offered higher incentives for such a choice. They are not morally bound to follow this path unless they are effectively, emotionally attached. Already, there are signs of that.

Elections to local bodies across Kerala were held in December 2020, and the Congress, the CPI (M)’s political rival, secured a majority in the Meenangadi panchayat. There is already speculation that the Wayanad climate-neutral project may go into a limbo if the new administration disfavours it.

COMPETING PRESSURES ON LAND

There is also a real estate boom across Wayanad owing to a new generation of entrepreneurs tapping into the tourism potential of the scenic hills. Some farmers reckon that selling a portion of their land to feed this construction boom will yield better returns than farming offers. Madhavan’s son, for instance, has sold a part of the family’s farmland, even going against his father’s wishes. “But I want to continue farming – if not for huge returns, at least to ensure my family’s sustenance,” says Madhavan.

Providing farmers longer-term incentives could help, reasons Ulka Kelkar, Director of Climate Change at global climate research outfit World Resources Institute India. The government, she says, is right to market the coffee from Meenangadi in the global market by branding its origin in a carbon-neutral place.

A number of countries, and even companies, are committing themselves to net-zero emissions in a few decades, Kelkar points out. Meenangadi’s farmers can benefit from such initiatives, she adds.

For now, farmers have largely welcomed the climate-neutral initiative. Madhavan was beaming when we met in January: he had just received `5,000 for planting a hundred trees under the ‘tree bank’ scheme. There is an element of self-interest in what farmers are doing, Madhavan acknowledges, but it is not all.

REALITY OF CLIMATE CHANGE

Places like Wayanad top the list of climate change hotspots in India. For farmers, climate change, and the risk of flooding or drought, are already part of day-to-day reality, notes Madhavan. They may not know the exact science behind it, but it is part of their lived experience, he adds.

There is widespread awareness in Wayanad that as the district develops — either as a service economy that caters to a widely used National Highway that passes through it, or as a generation of new entrepreneurs looks to turn the agrarian ‘wastelands’ into tourist constructions — it is getting warmer. “When I came here first, just four years ago, I needed a sweater to keep warm in January,” recalled Ajit. “Now, I can’t bear the heat in January.”

This is true elsewhere in Kerala, and more so in ecologically fragile places like Wayanad, experts point out. A government study noted that between between 1981 and 2016, only in four years had the State experienced a “normal” monsoon. Erratic rains are resulting in rain bombs like the megafloods of 2018, or the drought in 2017, the worst in a century. More generally, Kerala struggles for freshwater, says Dineshan V.P., scientist and faculty at the Central Water Resources Development and Management (CWRDM), a government-run water studies entity.

Kerala boasts of 44 rivers, but that is a misleading bit of statistic, he says. Going by nationally accepted definitions, major rivers should have a catchment area of 20,000 sq km; on that count, Kerala has none. It has four median rivers of 2,000- 20,000 sq km; the rest are smaller than that. “In fact, the State’s natural conservation systems have failed to an extent that the official machinery has to provide tanker water in ecologically fragile areas nearly every summer,” he says.

Most Indian States are similarly wracked by the ravages of climate change. Which is perhaps what gives Meenangadi’s ecological experiment a heightened relevance for other Indian cities and villages.

Meenangadi is a metaphor for all Indian villages, where the emphasis is on development, and all small towns that are growing and becoming bigger, says Kelkar. The decision they have to make is stark. “Do you want to choose a high-carbon pathway that locks you into a certain kind of infrastructure and investment for decades? Or will you choose an alternative set of technologies and infrastructure and investment, which is not only good for the global climate, but alsok for the local environment and the health of the people?”

Many other cities – in India and around the world – are carrying out similar ecological experiments as Meenangadi, points out Kelkar. For instance, Indore, in Madhya Pradesh, is drawing up plans to become carbon-neutral. Similar plans have been unveiled for the Union Territory of Ladakh. The Sikkim government is looking to bring the entire State under organic cultivation; Pune has a ‘climate action plan’ centred around a low-carbon pathway; and Andhra Pradesh is talking of smart villages. They will all be looking keenly for lessons from the experiment under way in Meenangadi village.

Back in the village, as Madhavan saunters around his farmland, there is a discernible spring in his step. The prematurely blossoming white flowers on the coffee bushes, which bear testimony to the ravages of climate change, are of course a source of concern. But in Meenangadi, that concern is contrasted somewhat by the hope inspired by a hundred trees planted afresh on the same farmland.

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH