They pass the acid test

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 02 issue 02 :: Mar - Apr 2023

By tweaking amino acids, scientists are formulating better drugs, adding alphabets to the book of life, and solving real-world problems.

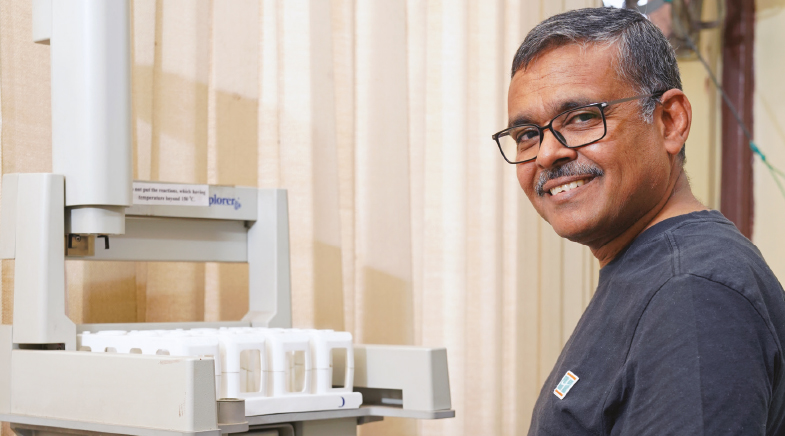

Rahul Jain had noticed the power and limitation of peptide-based drugs as early as 1995, when he was a post-doctoral researcher at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in Maryland, U.S. Scientists at NIH had synthesised a peptide that showed strong anti-malarial activity in microbial culture dishes. But when the experiment was done on animals, its anti-malarial activity disappeared.

Peptides are short chains of amino acids – usually not exceeding 60 in number – selected in different combinations from a list of 20. Peptides act in the body as enzymes, hormones and antimicrobials. The insulin hormone that regulates blood sugar levels is a peptide of 51 amino acids. The wide-ranging biological activity of peptides makes them useful as drugs in theory. But they haven't worked well in practice.

The NIH researchers had found that when administered, their peptide rapidly breaks down in the body. "Peptides are composed of natural amino acids and the body has enzymes that break them," says Jain, who is now a Professor at the Mohali-based National Institute of Pharmaceutical Education and Research (NIPER). Scientists like Jain have a plan to overcome this problem: replace some amino acids in the peptides with those not normally found in living beings.

Jain moved to NIPER in 1997 and has since been working on developing peptides as drugs. Specifically, he is interested in small peptides, those with only a few amino acids. They are cheaper to develop and, when tweaked a bit, are less likely to be cleaved by the body's enzymes. Such peptides are now beginning to enter the market as drugs.

PAST ISSUES - Free to Read

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH