Up in the air

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 04 issue 10 :: Nov 2025

How a solar eclipse led to the discovery of helium.

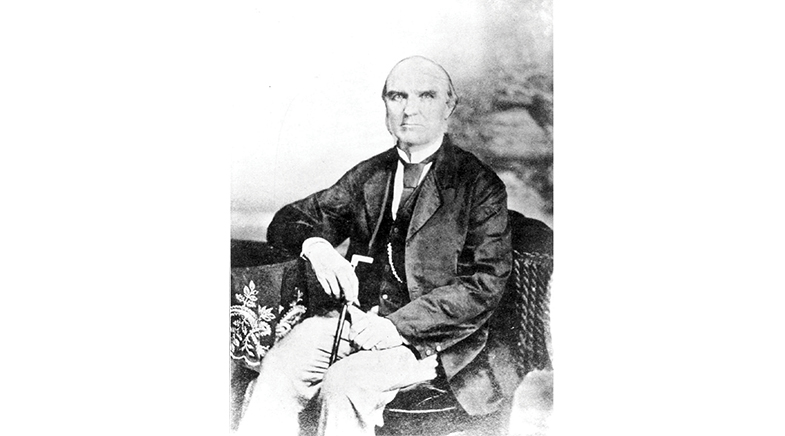

In 1870, when Germany laid siege to Paris during the Franco-Prussian War, the city's residents devised an ingenious escape route: hot air balloons. Among the escapees was French astronomer Pierre Jules Janssen. But Janssen wasn't fleeing for his life. He was chasing a solar eclipse that would be spotted over Algeria on December 22. Narrowly escaping gunfire from Prussian troops, he landed in a field more than 300 km away — and after tucking into a hearty meal provided by some generous farmers, made his way to Algeria (bit.ly/Helium-Escape). His daring escape, however, was for nought: an overcast sky dashed his hopes of observing the eclipse and confirming something he had seen two years earlier.

Two years earlier, the globe-trotting astronomer had been thousands of kilometres away in Guntur, in southern India. By then, using what was then a new device called the spectroscope, German scientists Gustav Kirchhoff and Robert Bunsen had shown that a heated gas produced a set of bright spectral lines at specific wavelengths, creating a unique barcode for that gas. For example, sodium vapour showed two yellow lines at 589 nm and 589.6 nm. It opened up an opportunity to discover gases and elements present in the Sun's atmosphere.

Jumping at this opportunity, Janssen travelled to Guntur, where a solar eclipse was predicted on August 18, 1868. He hoped that when the blinding light of the Sun's core was blocked temporarily, spectral lines from the outer layer would become clearly visible.

Janssen wasn't alone. The British government sent teams under James Tennant to Guntur and John Herschel to Jamkhandi to observe the eclipse, while Norman Pogson, the director of the Madras Observatory, went on his own to Machilipatnam. When the eclipse began, all of them spotted an unusual yellow line at around 588 nm just below the sodium lines, but everyone except Pogson initially dismissed it as belonging to sodium.

IN THE SHADOWS

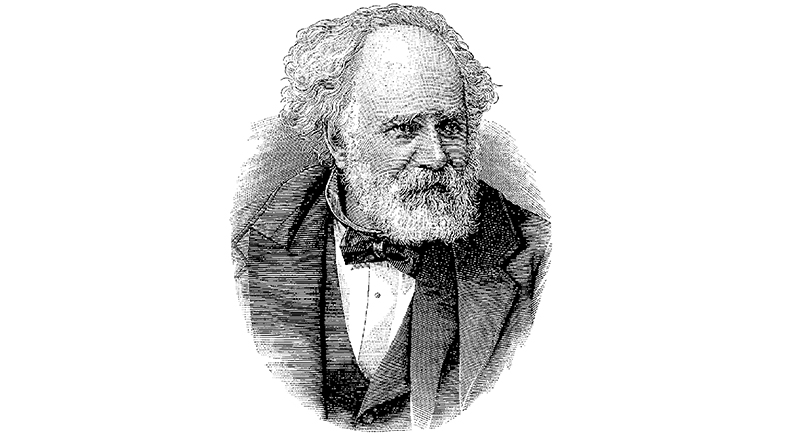

Norman Pogson, a British astronomer based in Madras, was the first to claim that the new spectral line noticed during the 1868 eclipse was distinct from that of other elements, but his observations were ignored — possibly because he was not well-liked due to his constant complaints about finances and offensive remarks about the "native staff" (bit.ly/Pogson-Staff). The government printed just three copies of his report, relegating his contributions to a footnote in the helium saga.

PHOTO: WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

When Janssen looked more closely at the spectral lines in the following days, he was able to focus the spectroscope precisely at the Sun's edge to capture the yellow line without needing an eclipse. A few months later, Norman Lockyer, an amateur British astronomer, also spotted the same line without an eclipse.

Lockyer's letter to the French Academy of sciences arrived on the same day (October 26) as Janssen's much-delayed letter dispatched from India. The academy credited both with devising a technique to view spectral lines and identify elements in the solar atmosphere. Lockyer later attributed the line to a novel element that he called helium after the Greek word for the Sun, helios.

DMITRI'S DISMISSAL

Among the scientists who did not accept that such an element could exist on Earth was Dmitri Mendeleev, who left it out of his iconic periodic table published in 1869. But in 1895, when William Ramsay extracted helium gas from a radioactive mineral found on Earth — and later co-discovered similar gases — the table was expanded to include this new group of noble gases.

Lockyer would go on to found the journal Nature and teach astronomy at the Royal College of Science, while Janssen continued his eclipse-chasing adventures. The duo became close friends — Lockyer's recommendation apparently prompted the British government to secure permission for Janssen to leave Paris safely during the 1870 siege (bit.ly/Jules-Janssen). But Janssen, of course, declined and decided to make a more dramatic exit.

Ranjini Raghunath is a Bengalurubased science writer and editor.

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH