Breathing free

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 03 issue 09 :: Oct 2024

A metallic monstrosity, the 'iron lung' saved thousands of polio patients.

By afternoon on October 13, 1928, eight-year-old Bertha Richard was dying. Rushed to the Boston Children's Hospital the previous day, the young polio patient's lung and chest muscles were paralysed, and her lips were turning blue from lack of oxygen. Jonas Salk's life-saving vaccine was still far away in the future.

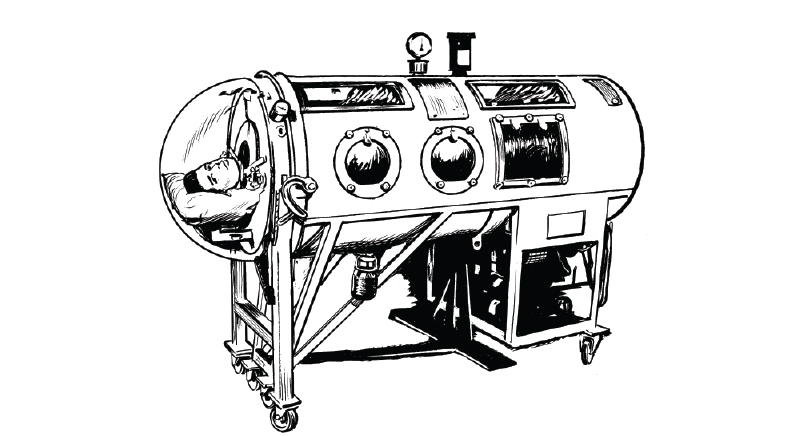

As a last resort, Bertha's doctors rolled her into a cylindrical metal tube completely sealed except for a hole for her head to stick out. It was an experimental device designed by engineer Philip Drinker and physician Louis Shaw. Bellows at the bottom sucked air out from the tube – the vacuum it created forced Bertha's lungs to expand and draw in oxygen. When air was pumped back into the tube, her lungs deflated. As the device pushed air in and out, her breathing slowly normalised. Fifteen minutes later, she spoke up, asking for ice cream. Drinker, who was nearby, started crying in relief (bit.ly/Drinker-Shaw).

Although Bertha died a few days later, Drinker and Shaw's 'iron lung' saved the lives of thousands of other polio victims in the following years.

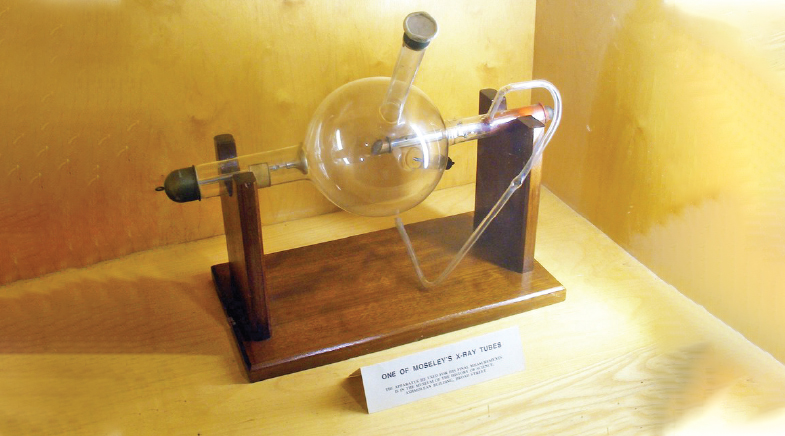

Born in 1894, when polio first emerged in the U.S., Drinker was an industrial engineer interested in fixing pollution and safety issues in aircraft and mines. In 1923, he became an instructor at the new School of Public Health at Harvard. There, he was intrigued by independent experiments on artificial respiration by his older brother, Cecil, and Louis Shaw. Working with Shaw, he designed a cylindrical metal tube with motors from used vacuum cleaners to pump air in and out. They found that it could keep a paralysed cat alive for hours. Securing funds from a consortium of companies, Drinker and Shaw scaled up their design to save workers affected by gas poisoning and electrocution.

One day, Drinker was called to fix equipment he had designed for newborn nurseries at the nearby Boston Children's Hospital. He happened to visit a ward for terminal patients with polio, the disease that had already affected thousands across the country, including the future President, Franklin D. Roosevelt. What Drinker saw shocked him: rows of paralysed children struggling to breathe, some of them dying as he watched. "He could not forget the small blue faces, the terrible gasping for air," his sister Catherine recounted (bit.ly/damn-machine).

DAMN MACHINE

Although his invention saved many lives, Drinker was irked by the excessive attention it received (bit.ly/damn-machine). Even so, he sued a rival, John Haven Emerson, who had designed a cheaper, less bulky version of it. Emerson, however, argued that aspects of Drinker's design had been patented by others earlier, and that such life-saving technology should be "freely available". Drinker lost and even had his own patents revoked.

This led Drinker to improve his design to help polio patients. When the prototype was ready, Bertha was the first patient to use it. The machine kept her alive and breathing normally for almost a week before she succumbed to pneumonia. The second patient, a student, made a full recovery. Word spread, and the iron lung soon became a fixture in hospitals across the country and abroad, until the polio vaccine came along in 1955.

A 'LUNG' LIFE

When Paul Alexander was wheeled into the iron lung in 1952, he was only six. He spent the next 72 years living inside the machine that kept him alive, exiting it for only a few hours at a time. Though his entire body was paralysed from the neck below, he became a successful lawyer and author, and amassed a considerable following on TikTok before his death in March 2024 (bbc.in/4ezQOMm).

Though the iron lung's use dwindled afterwards, it inspired many future medical innovations, including intensive care units in hospitals (bbc.in/3MSYygT) and modern-day ventilators that saved countless lives during COVID-19. One of its two last users, Paul Alexander, "lived" in the lung for more than 70 years until he died in March 2024.

Ranjini Raghunath is a Bengaluru-based science writer and editor.

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH