Cards on the table

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 04 issue 11 :: Dec 2025

In the 1860s, a Russian teacher laid the foundation for chemistry’s most recognised matrix.

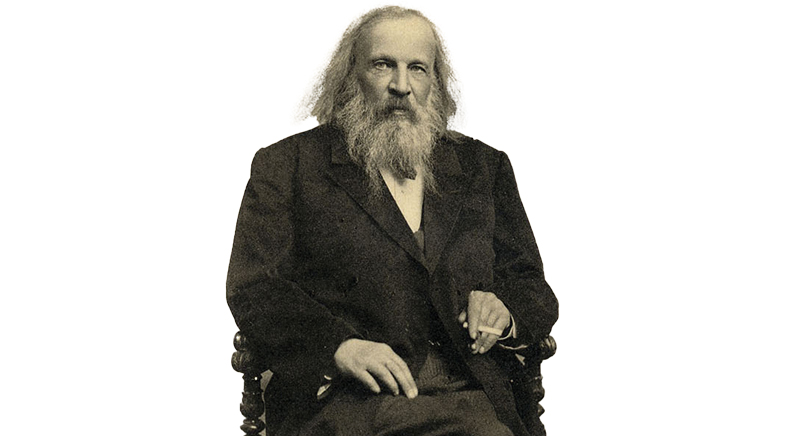

With a long, flowing beard and wild hair that he deigned to trim once a year, Dmitri Mendeleev gave off more sorcerer than scientist vibes. Adding to this aura was a pack of cards he carried around in his pocket. But Mendeleev wasn’t trying to trick anyone; he was trying to solve a fundamental problem in the 1860s – how were different elements related to each other?

Growing up in Siberia, Mendeleev had a hard childhood. His father’s illness and financial troubles forced his mother to take Mendeleev and his sister to Moscow and then to St. Petersburg for higher education. Tragically, his mother and sister died soon after. Mendeleev finished his graduate degree in chemistry with honours in 1855.

In 1859, Mendeleev received a fellowship to spend two years in Germany. There, he got the chance to attend a landmark 1860 conference in Karlsruhe, where scientists unanimously agreed upon how to calculate the atomic weight of elements. Mendeleev then returned to Russia and took up teaching at St. Petersburg Technological Institute, quickly gaining popularity for his engaging lectures.

The 1860s were an exciting time for chemists, with new elements being discovered almost annually. But Mendeleev realised that his pupils struggled to understand these different elements without a proper organisational structure, and decided to write a textbook for their benefit.

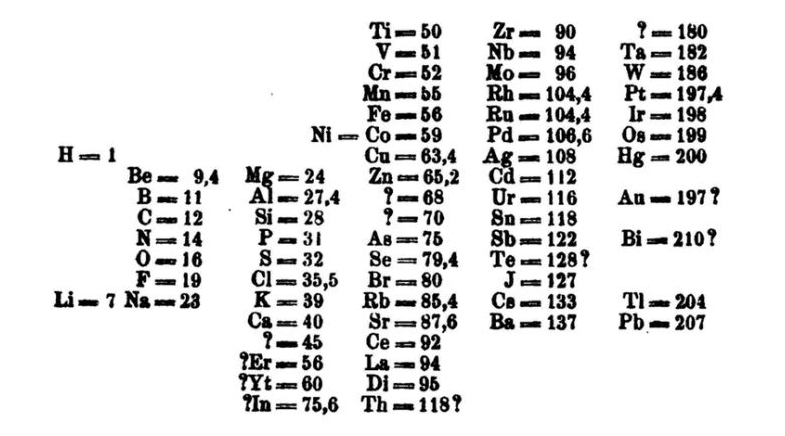

During his research for the book, he wrote down the symbols and atomic weights of all 63 elements known at the time on a set of note cards, and kept shuffling them around to see if a pattern emerged. On February 17, 1869, while arranging elements by atomic weight, he noticed (bit.ly/mendeleev-table) that elements in the same vertical columns showed similar properties; he called this the Periodic Law. The following month, Mendeleev presented the first version of what would become the periodic table at the Russian Chemical Society.

HIGH FLIER

Mendeleev once flew solo in a hot-air balloon (bit.ly/mendeleev-balloon) to observe a solar eclipse after the pilot refused to accompany him because of dangerous weather conditions. Risking life and limb, he flew the balloon up to more than 11,000 feet and took atmospheric measurements before making a bumpy landing. He earned a medal from the French Aerostatic Corps for his effort.

Around the same time, German chemist Lothar Meyer devised a very similar periodic table but published it only after Mendeleev did. Mendeleev also went a step further: he left gaps for yet-to-be-discovered elements in his table and predicted their properties based on their positions. He used Sanskrit prefixes like eka-, dvi-, and tri- to denote their connections to existing elements. For example, gallium – which was discovered six years later with properties closely matching his predictions – was called eka-aluminium.

Although British scientist Henry Moseley later showed that elements should be arranged by atomic number and not atomic weight, Mendeleev’s original predictions of elemental positions largely held true. The periodic table underwent several modifications in the decades that followed, most notably making additional space for rare gases, lanthanides and actinides.

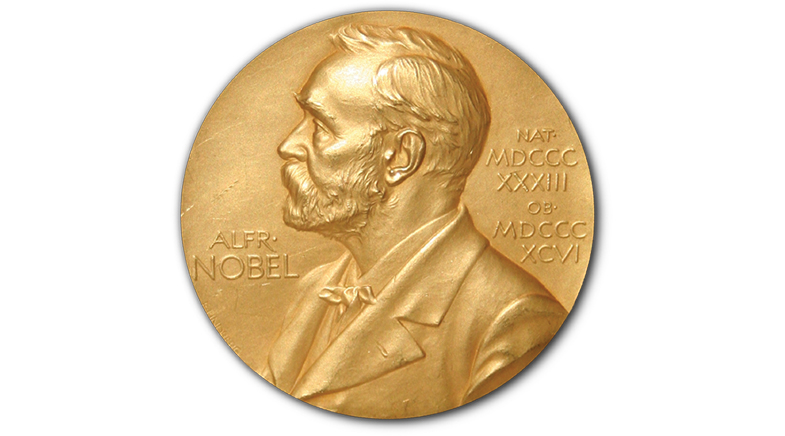

ELUSIVE NOBEL

Mendeleev was nominated nine times for the Nobel Prize, but failed to win it. Some believe (bit.ly/mendeleev-nobel) that he was denied the prize partly by the influence of another Laureate. Swedish chemist Svante Arrhenius evidently held a grudge against Mendeleev for dismissing his theory on how electrolytes dissolve in water. He also argued that Mendeleev’s work was too old to be considered.

PHOTO: WIKICOMMONS

Mendeleev also pursued a number of interests in his lifetime, from photography and luggage manufacturing to agriculture, geology, and meteorology. An outspoken liberal, he left his position at St. Petersburg in 1890 in solidarity with protesting students: his last lecture was broken up by police who feared that he would incite students to riot. He died in 1907, and at his funeral procession, a group of students carried a banner showing the periodic table of elements to honour his legacy.

Ranjini Raghunath is a Bengalurubased science writer and editor.

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH