Strokes of life

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 04 issue 08 :: Sep 2025

A German illustrator and naturalist laid the foundation for modern entomology.

When Maria Sibylla Merian stepped down on the shores of Suriname, a Dutch colony in South America in the 17th century, she was transported to a whole new world. It was September 1699. The 52-year-old German naturalist and her daughter had just taken a perilous two-month voyage across the Atlantic Ocean from Amsterdam. Merian had long dreamed of making this journey to see creatures she had only observed as fossils and specimens.

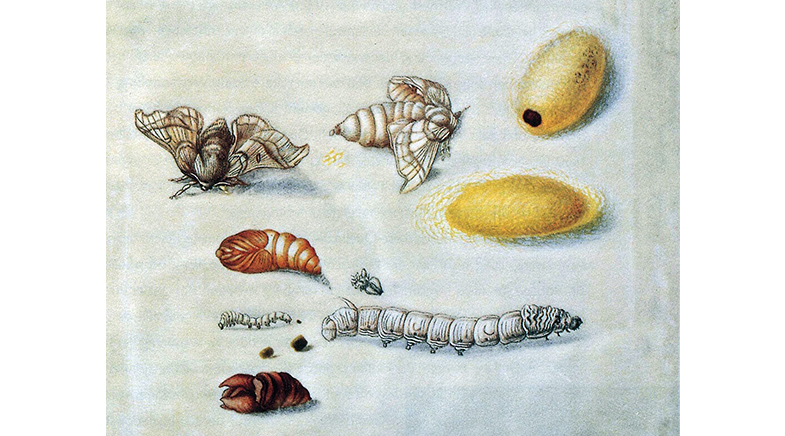

Born in Frankfurt in 1647, Merian developed an early fascination for insects. At 13, she began raising caterpillars at home in wooden boxes, feeding them lettuce leaves and watching them transform into moths or butterflies. She also learned to paint in her artist stepfather's workshop and would later marry one of his apprentices.

SABOTAGE AND SEXISM

Some of Merian's drawings were criticised as fanciful, such as her illustration of a large spider preying on a bird, which inspired the Dutch name for tarantula, vogelspin ('bird spider'). One male naturalist also accused her of ignoring facts that "every boy entomologist would know" (bit.ly/Hidden-Woman). When her work was reprinted after her death, errors and imaginary drawings were added in by unknown saboteurs. These diminished her contributions until they were recognised again in the late 20th century.

During her lifetime, Merian published many detailed illustrations, including a two-part series on the metamorphosis of caterpillars, depicted as engravings on copper plates. In those days, people believed that insects were "beasts of the devil" born spontaneously from mud or rotten meat. Merian was among the first to disprove this theory by portraying the insects' complete life cycle.

Unhappy with her marriage, Merian moved with her daughters briefly to a religious commune, after which her husband divorced her. Later, she moved to Amsterdam, where she first chanced upon insect and animal specimens brought in by Dutch traders from Suriname. She wondered about the creatures' lives and yearned to see them in their natural habitat. After selling her paintings to finance her journey, she set sail with one of her daughters. In Suriname, she braved heat and mosquitoes and took the help of indigenous enslaved people to slash through thickets, ride on riverboats into the rainforest, and collect and observe various kinds of insects and small creatures.

SPOTLIGHTING SLAVERY

Merian also used her work to shine a light on the enslavement of indigenous and African people. Although she took their help extensively for her forest expeditions, she also tried to record their sufferings in her notes. In one instance, she wrote: "The Indians, who are not treated well by their Dutch masters, use the seeds [of the peacock flower] to abort their children, so that they will not become slaves like themselves."

In addition to drawings, Merian made vivid observations. She described, for example, how an ant species could eat "whole trees bare as a broom handle in a single night" (bit.ly/Maria-Merian). She noted the local names of plants and insects, and how the indigenous people used them. Her drawings depicted numerous natural phenomena — from female toads carrying fertilised eggs on their backs to cocoa plants growing in the shade of banana leaves. She also highlighted the relationships between these creatures and their surrounding environment.

Merian planned to stay in Suriname for five years, but illness forced her to return in two. She took back with her a tidy collection (bit.ly/Merian-Specimens) of dried plants and insects, and animal specimens (plus a crocodile preserved in alcohol). In 1705, she published her magnum opus, Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium, a compendium of 60 beautifully engraved copper plates depicting the lives of Surinamese insects along with plants and animals in their natural habitat. Naturalists such as Carl Linnaeus later used her work to identify dozens of new plant and animal species.

Merian died of a stroke in 1717. Russian tsar Peter the Great was among many collectors who bought and preserved her original illustrations.

Ranjini Raghunath is a Bengalurubased science writer and editor.

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH