Voices without wires

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 04 issue 01 :: Feb 2025

An eccentric American farmer was one of the earliest pioneers of wireless communication.

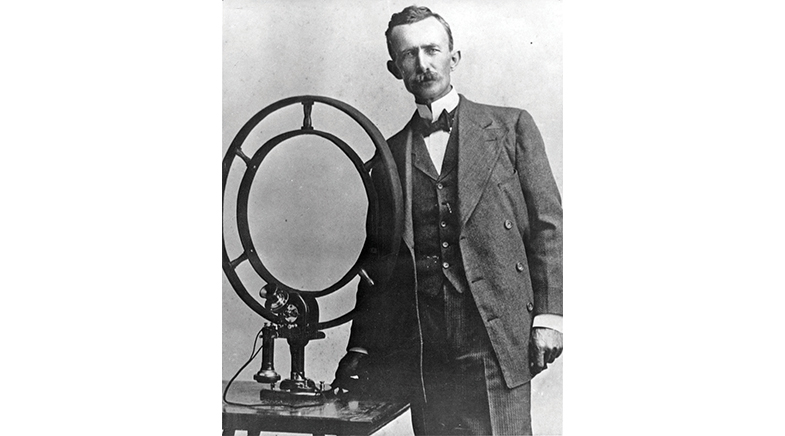

On January 1, 1902, curious spectators gathered in front of the courthouse in the town of Murray in Kentucky, in the U.S. As they watched, Nathan Stubblefield (pictured), an eccentric local farmer and inventor, and his 14-year-old son Bernard, brought two square black boxes and placed them more than half a mile apart. When Bernard spoke into a telephone receiver hooked up to one of the boxes, his voice could miraculously be heard clearly from a receiver connected to the second box, as well as five other boxes placed across town. It was, according to some reports, the first time someone had broadcast the human voice over short distances using a wireless device.

News coverage of the demonstration was highly positive. The Sunny South claimed (bit.ly/wireless-sunny) that it would soon become “world history”. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch published a front-page story by a reporter who visited and tested the device on the inventor’s farm. Such reports catapulted Stubblefield to national fame: within months, he was touring the country giving demonstrations.

LOCAL LEGEND

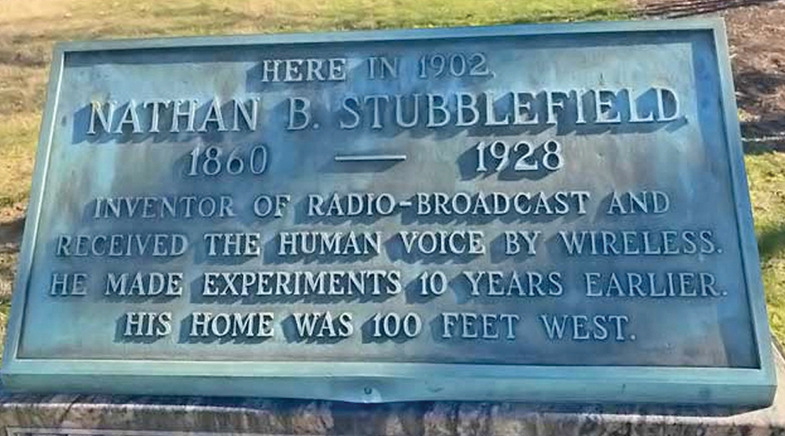

For years after Stubblefield’s death, experts debated whether his voice transmissions counted as radio broadcasts since he had used electromagnetic induction, not actual radio waves, to transmit sound. But to Murray residents, their town was the “birthplace of radio”. In 1930, they erected a marker on the Murray State University campus (pictured).

Born in Murray, Stubblefield was a farmer who moonlighted as an electrician. Growing up, he spent hours poring over Scientific American at a local news office, reading about the works of scientists Nikola Tesla, James Maxwell and Heinrich Hertz. In 1888, he patented a mechanical telephone that was installed in a few States, but it was soon supplanted by Alexander Graham Bell’s electrical wired telephone.

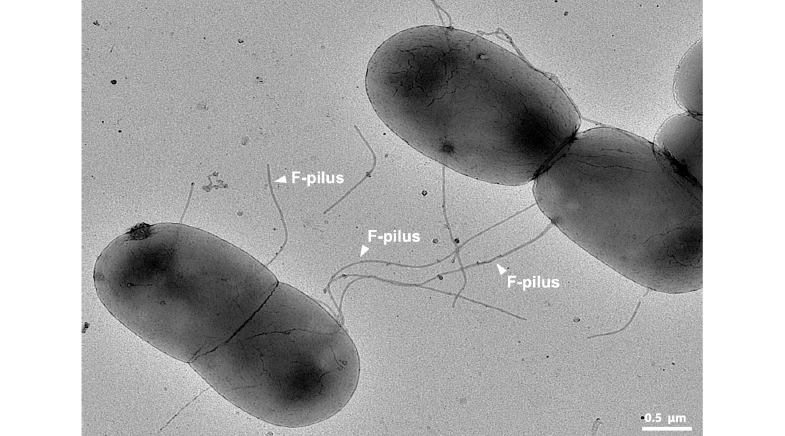

Undaunted, Stubblefield turned his sights to wireless communication, working in secret on his 85-acre farm. His device used electromagnetic induction to convert sound into an electrical signal that was picked up by a receiver and converted back into sound (bit.ly/wireless-story). The transmitter and receiver were anchored to the ground using steel rods, and used the Earth itself as the conducting medium, without needing wires. He also developed a battery-operated version that used copper coils instead of the Earth to transmit an electromagnetic audio wave. In March 1902, in another public demonstration along a bank of the Potomac River in Washington, his device was able to pick up voice messages transmitted ashore from a steamer over a distance of about 500 metres.

STRANGER DANGER

Stubblefield was secretive about his work; he homeschooled his children and forbade them from inviting friends over, so that they wouldn’t “leak” the secrets behind his inventions. For years, he rejected lucrative offers to commercialise his devices, scaring away potential investors by using alarms that went off when someone approached his farm, and meeting them at the entrance with his shotgun.

Although Stubblefield was initially reluctant to commercialise his device, he eventually partnered with a New York-based company that bought the rights to his invention in exchange for stock. He soon realised that the company was indulging in fraudulent practices and cut ties with it. In 1908, he got a patent on the portable wireless device. But it was too late. By then, radio systems that could broadcast over hundreds of miles had become widespread.

The device used electromagnetic induction to convert sound into an electrical signal that was picked up by a receiver and converted back into sound.

The next two decades were tough for Stubblefield financially and personally: he failed to find funders for his inventions, and his family sold his farm and moved out, leaving him to live alone in a shed. On March 28, 1928, his body was discovered days after his death. In 1948, the town’s first radio station was named after Stubblefield, in honour of his contributions to wireless voice transmission.

Ranjini Raghunath is a Bengaluru-based science writer and editor.

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH