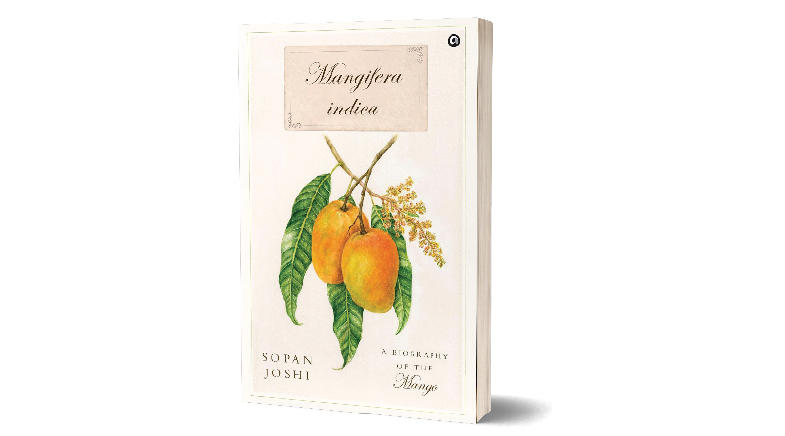

A slice of mango

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 03 issue 09 :: Oct 2024

An encapsulation of the many ways in which India's favourite fruit has influenced culture, history and the economy.

Having grown up on a staple summer diet of mangoes and mango lore, I love the fruit, and can distinguish between Dashehri, Chausa, Kesar, Imam Pasand, Badami, Banganapalle, Mallika and other varieties. The prospect of sinking my teeth into journalist Sopan Joshi's book Mangifera indica and harvesting yet more mango stories was, therefore, too juicy to pass up. Joshi encapsulates the many ways in which the fruit has influenced the culture, history, and economy of India and beyond. The book is replete with tales of mango varieties of India – from the legendary Alphonso and Langda to obscure ones like Sukul; and anecdotes about, among others, India's oldest mango tree and Asia's largest mango orchard.

Joshi takes readers to the old orchards of Murshidabad and Darbhanga, home to little-known mango varieties, and acquaints us with the difference between seed-grown trees and grafted ones. We learn of Vantalamammidis ("mango kitchens") of Andhra Pradesh, and amrais of northern India, which were mango groves where travellers could take shelter and cook. The author then takes readers along thandi sadaks (cool, tree-lined avenues), which exist even today in many northern Indian towns.

The subcontinental history of mangoes is an enduring one: there is evidence of mango consumption by people of the Indus Valley Civilization. A dig site in Farmana, Haryana, has yielded traces of mango used in a brinjal curry cooked about 4,500 years ago. The oldest-known mango fossil, about 25 million years old, is at the Birbal Sahni Institute of Palaeosciences, Lucknow; it is a mango leaf preserved in black shale that was found in a coal mine in Tinsukhia, Assam.

The Indian tectonic plate collided with the Asian plate 50 million years ago. But it took another 27 million years for the land connection to happen. Which means the fossil is from a period when India was still an island. To many researchers, this establishes that the mango evolved on the Indian plate, but as it evolved, its 'centre of diversity' — the region where most of its wild species exist – shifted eastward. "Southeast Asia has the largest number of wild mango species. Indonesia has thirty-three, Malaysia twenty-nine, Thailand thirteen, and Vietnam has nine. India has nine species, including Mangifera indica and all its 1,000-odd varieties; five of those species are from the Andaman and Nicobar Islands that are close to Myanmar, Thailand, and Indonesia," notes Joshi.

The author then dives deeper into the origin of the mango plant, and charts the evolution of angiosperms, the flower and fruit-bearing plants. He notes that mangoes evolved in tandem with primates, relying on the sight and smell of the latter for seed dispersal: this theory of co-evolution was first propounded by anthropologist Robert Sussman.

In the book's final section, the author shines a light on the modern-day custodians of mangoes: farmers; breeders, who develop new varieties; and plant pathologists, who work to protect mango trees from pests and diseases. According to the breeders, an ideal mango is a variety that bears fruits every year, has short-sized trees, medium-sized pleasant-flavoured fruits, and a resistance to bacterial and fungal diseases. "But the two most successful varieties created by scientists in India are Amrapali and Mallika. Both are crosses of Neelum with Malihabad's Dashehri," notes Joshi. However, neither is as popular as, say, Alphonso or Langda.

Just as the stereotypical Briton talks about the weather, Indians talk about the mango, reckons the author.

Breeding is necessary for developing resistance to the bacterial and fungal diseases and pests that afflict Indian mangoes. But breeding mango varieties has been tough because it is "nature's wild child", Joshi notes. How a mango tree behaves depends on the soil, air and water, and the immediate environment in which it grows. Perhaps the answer to growers' problems lies in the vast pool of wild mango varieties in India; some of them are unaffected by fungal diseases; others can withstand floods or grow in cold, high altitudes.

Mangoes are, as the author says, India's favourite "bribe": a gift that no one can refuse, and one that opens many doors. "It is both our great distraction and a reliable means of conversation," he adds. Just as the British talk about the weather, Indians talk about the mango. This book, with its sweet after-taste, is sure to add many new strands to mango talk.

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH