Waiter, there’s a chemist in the kitchen!

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 01 edition 01 :: May - Jun 2021

An appetising book that uses the tools of modern science to document Indian culinary traditions.

AS SOMEONE who has been cooking for more than 30 years, here are a few things I did not know before I read this book but am glad I do now.

That hard-to-digest carbohydrates proliferate in rajma, which become food for gut bacteria who convert it to gas (the flatulence is good, since it spurs the growth of healthy gut bacteria). That marination does not penetrate beyond the surface of meat, but brining does, improving flavour and preventing the loss of water from muscle tissue. That the key to using and understanding yoghurt in a gravy is to whisk in some starch to strengthen the emulsion so it does not break down when heated.

The daily act of cooking food is, of course, intrinsic to our survival. But since humans are no longer simple hunter-gatherers, it is, to the interwoven community of Instagrammed modern mankind, so much more. Cooking now encompasses the culinary arts, science, tradition, pleasure and intuition.

I am given over mainly to the last, cooking as I have all these year by my wits more than reason, turning out food for my family through trial and practice. I write a bi-monthly cooking column, I do not watch MasterChef Australia, a wildly popular televised competition of home chefs, and I am not a big fan of cookbooks, although I possess nearly 100.

So, to get me interested in a book that deconstructs the science of Indian cooking is no mean feat. As a former science writer, I do confess to more than a passing interest behind the science of anything, but this book is meant to be many things to many people. It is a guide to the home chef, with tips to improve basic skills, such as browning onions or using a pressure cooker better. It is a lure to the scientist to explore the joy of food beyond the science. And it hopes to be of interest to the lay reader interested in good writing.

I liked the fact that Krish Ashok says the book will not make you a chef but a better home cook, which indeed is what I am.

Ashok’s central argument is to “dexoticise” Indian food, use “the tools and language of modern science and engineering” to analyse and document myriad Indian culinary traditions. By not doing so, he writes, we are doing the “food equivalent of lip-synching to a pre-recorded track”.

DEMYSTIFYING THE DAL

Unlike Western cooking, writes Ashok, Indian cuisine suffers from a historical lack of record-keeping and, subsequently, standardisation. “Art is and should be hard to master, but if the craft is hard to get right, then the documentation is pretty inadequate… By treating our culinary tradition as something sacred, artistic and borderline spiritual, we are doing it a great disservice.”

He uses Western music as a metaphor for the power of simple visual notation “that is able to accurately capture every nuance” and explains why you can play a Bach concerto as the great composer himself did in the 18th century.

Since Ashok favours — and makes a strong argument for — transforming cooking into an engineering discipline, “one with standardised methods and a finite set of easy-to-remember general principles that work for all kinds of dishes”, his reductive culinary philosophy is: “Cooking is ultimately chemical engineering.”

This is both the book’s strength and weakness. The food science he writes about is excellently collected and deconstructed, but it could get somewhat overwhelming for his major target audience: the lay reader who cooks.

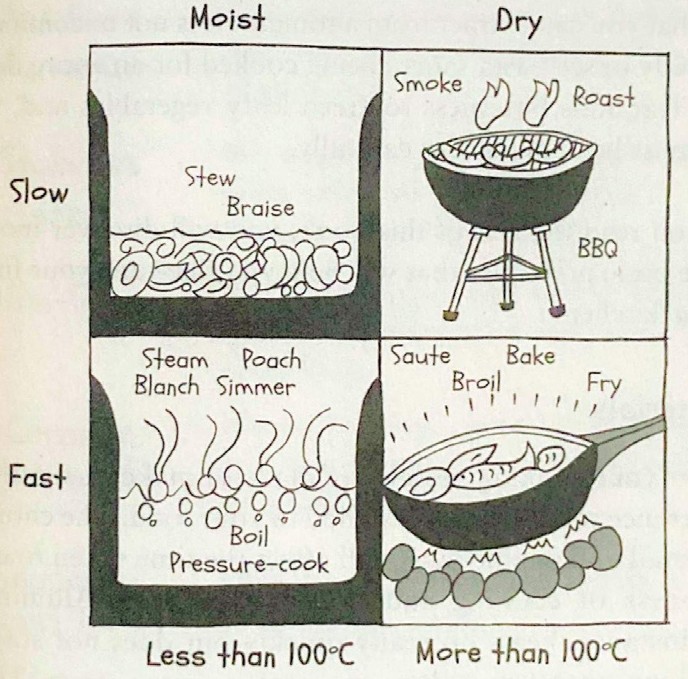

We learn about the basic physics of heat, density, air pressure, conduction, convection, radiation, denaturation and — most importantly for the Indian cook — the Maillard reaction, which explains the browning of food. There is a whole chapter on the science and techniques of browning and caramelisation of onions, garlic, cabbage and potatoes, written with verve and humour.

For instance, he explains how a hot light source generates infrared radiation to cook food, as with a shawarma. Technically, everything, including us, radiates some energy, but it is not enough to cook food. “But if the object in question is reactor number 4 at Chernobyl,” he observes, “the results are not pretty.”

Ashok casts new light on everyday Indian cooking. He recommends we use spice powders in good time before they turn to “flavourless sand (hint: use a spice or coffee grinder to make spice powders when you need them). There is a long analysis of whole spices and blends and lengthy expositions on the science of sugar, salt and flavour. His oeuvre is vast and includes the science behind using yoghurt, tamarind, mango, vinegar and tomato.

The food science in the book is excellently deconstructed, but it could still get somewhat overwhelming for the lay reader who cooks.

THE SMELL TEST

I also found most fascinating his exposition on orthonasal olfaction, or what you smell before you eat, which is quite different from the taste, which is why cheese may smell strange, flame-roasted brinjal may smell acrid and metallic and – my favourite – dried fish, may smell extremely fishy.

The book abounds in handy cooking tips: for the best flavour, brown ingredients before adding them to gravies; use a batter of maida, salt and vodka for pakoras (alcohol reduces gluten development, stops surface starches from absorbing too much water, making pakoras crisper); use a pinch of baking soda to brown potatoes, blanch green vegetables, tenderise tough meat, make fluffier omelettes and browner dosas. He has “algorithms” for soft chapatis and perfect idli/dosa batter.

Science, in other words, in the service of breakfast, lunch, dinner — and everything in between.

Samar Halarnkar is a parttime journalist, part-time cook, full-time father and the author of A Married Man’s Guide to Creative Cooking (And Other Dubious Adventures).

@samar11

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH