It takes guts...

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 04 issue 11 :: Dec 2025

...for the vulture, the python, and you. One being's meat is another's poison.

Vultures are in short supply today for a variety of reasons. There was a time, a few decades ago, when carrion at the roadside would be speedily polished by a circle of them. Rotting carcasses are not the most odorous or otherwise appealing of meals, but this is a niche, multi-course meal for this scavenging bird. Were you — just a thought experiment, please — to partake of such a meal, even after cooking it well, you will be in serious trouble. While the nasty bacteria and parasites also feasting on the carcass will be killed by cooking, many of the toxins the bugs release are heat-resistant and will cause us to be severely ill, if not to die. The vultures, though, delight in what to us is a deadly meal, and move on to a vantage from where they can next find their supper.

The python occupies another, and very different, culinary niche. Hiding in plain sight in the dense jungle growth, it waits for its prey to come by. Swiftly, it strangles the boar, and by an amazing feat of peristalsis, the entire animal is shoved into its gut. The python then lies, pretty much immobile, till its food — fur, skin, bones, innards and muscles — is thoroughly digested. Here, too, for us, this approach of swallowing large volumes of food whole is ill-advised.

Our ancestors, dating back approximately 2.5 million years, began to adopt an omnivorous diet. Changing ecology perhaps altered the availability of plant-based food that could be digested, and hominins started feeding on small animals, fish and insects. Animal proteins packed a punch of calories, also providing many vitamins and micronutrients. However, it was only much more recently, about three-quarters of a million years ago, that 'we' discovered that fire could be used, not just for keeping warm, but for cooking. Omnivorous diets and cooking, some speculate, powered the evolution of a large brain, disproportionate in size to the rest of our body, when compared with our ape cousins. Our diet also powered the evolution of our digestive system and gut. We are exhorted to chew our food well, and our ancestors did so, too, to break down what we eat, starting with chemicals in the saliva in our mouth.

THE ACID TEST

When we marvel at animals, including humans, we rarely focus on the stomach and the gut. The digestive system of vertebrates relies fundamentally on a highly acidic gastric environment, produced by the secretion of hydrochloric acid into the stomach lumen. This process is orchestrated by specialised cells located within the gastric glands of the stomach lining. These cells utilise a complex transport protein, to drive hydrogen ions into the stomach lumen, making the stomach acidic. The maintenance of high gastric acidity facilitates chemical digestion; more critically, it often serves as the host defence mechanism. The stomach acts as a powerful ecological filter, eliminating the vast majority of microbial contaminants ingested with food before they can pass into the absorptive small intestine and colonise the host.

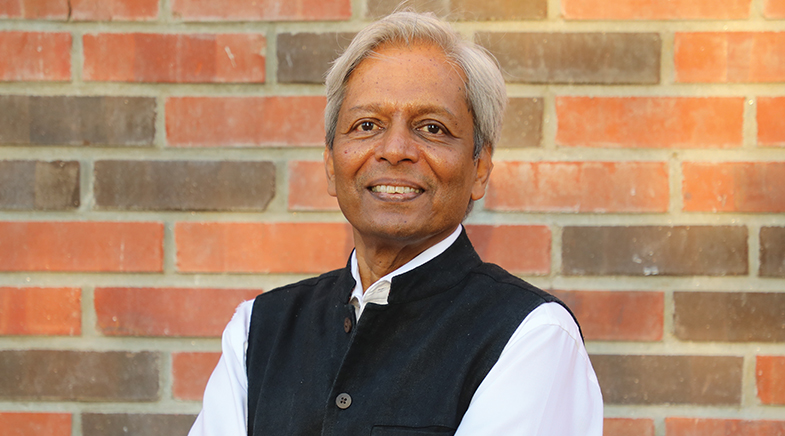

A monthly column that explores themes on nature, nurture and neighbourhood in the shaping of form and function.

Species consuming high-risk diets, such as carrion, which is inherently contaminated, or structurally resistant materials like bone, must deploy significantly stronger acid as a protective measure compared to species feeding on lower risk levels, such as herbivores. The necessity for extreme acidification represents a metabolic trade-off. The production and maintenance of concentrated hydrochloric acid demands high continuous expenditure of energy. The presence of ultra-high acidity is a powerful physiological signature indicating that the benefits of pathogen defence and complex structural breakdown far outweigh the continuous, high energetic burden required.

Although the majority of ingested organisms are destroyed in a highly acidic environment, certain highly specialised and acid-resistant bacteria, such as poisonous Clostridia and flesh-destroying Fusobacteria, can survive the vulture's hyper-acidic stomach. However, rather than harming the scavenger host, these surviving organisms often establish themselves in the large intestine where they actively contribute to digestion. By breaking down the remaining nutrients that are difficult to process, they enhance the overall efficiency of the digestive system. This strange phenomenon demonstrates that the stomach's highly acidic environment not only serves to exclude pathogens but also selects for a highly adapted, acid-tolerant microbial community that functions symbiotically with the host, maximising nutrient extraction from a challenging diet.

The search for the animal with the most acidic gut unequivocally leads to obligate scavenging birds, specifically vultures. This group, which feeds almost exclusively on decaying carcasses, exhibits the highest acidity documented among vertebrates.

Any systemic or regulatory failure leading to a lowering in acidity would likely compromise their primary defence mechanism, resulting in lethal infection from the massive bacterial loads they routinely ingest. The white-backed vulture (Gyps africanus) has among the highest stomach acidity recorded. Even more impressively, the bearded vulture (Gypaetus barbatus), the only known animal whose diet is composed almost entirely of bone, has even higher acidity. The digestive acid of vultures is recounted as comparable in corrosive strength to battery acid, and over 100 times more potent than average human gastric acid.

While obligate scavengers represent the pinnacle of sustained acidity, other groups also deploy powerful gastric acid to manage their specialised diets, though often with greater variability or episodic production. Scavenging mammals are close competitors. Species like the hyaena demonstrate similar adaptations, possessing extremely high stomach acidity. As with vultures, this high acidity allows mammalian scavengers to utilise highly contaminated and structurally resistant carcass components, enabling them to occupy a critical niche in carcass breakdown.

Crocodilians, and some snakes such as pythons, known for ingesting large, intact prey, produce highly potent gastric juice, with measured acidity values typically ranging from a tenth to a hundredth of that of vultures. Their feeding strategy of large infrequent meals requires a substantial, episodic surge of acid production to break down tough hides, connective tissue, and bone. While their minimum acidity values overlap with those of obligate scavengers, their strategy tends toward rapid, high-volume production timed precisely with feeding, rather than continuous low-level maintenance.

Pythons' large meals require a massive, instantaneous digestive surge. To meet this challenge, they have evolved a specialised cardiovascular mechanism.

Human gastric acidity is a tenth to a hundredth of that of scavengers; this is still remarkably high when compared to most other animals and specifically to many non-scavenging primates. Many of our monkey and ape cousins have very alkaline stomachs. This unusually strong human acidity has led to the hypothesis that early hominins were effectively facultative scavengers. High gastric acid levels would have been essential for protecting our ancestors from pathogens acquired through opportunistic consumption of remaining carcasses, a diet similar to that of modern hyaenas and vultures. This shared need for disinfection in consuming high-risk food sources resulted in the convergence upon extremely acidic gastric environments, highlighting the deep antiquity of the stomach's primary role as a pathogen barrier.

HIGH ON ALKALI

In stark contrast to acid-producing scavengers, or even humans, foregut herbivores (cows and sheep) demonstrate the low-acidity extreme, maintaining a very alkaline proximal stomach (fore-stomach). This alkaline environment is deliberately preserved because the primary digestive function in this chamber is dependent upon cellulolytic microbial fermentation, which breaks down their plant diet. The maintenance of this high alkalinity is functionally critical. If acid production increases and reduces fore-stomach alkalinity, the result is the potentially fatal affliction known as acidosis. Scavengers prioritise host defence via acid, while foregut fermenters prioritise symbiont microbial welfare via acid suppression.

SCAN & WATCH

Maintaining sustained gastric acidity in obligate scavengers requires extraordinary physiological capacity, pushing the limits of standard acid secretion mechanisms into the stomach. Acid secretion into the stomach is balanced by the concurrent release of bicarbonate (an alkali) into the blood, and this requires robust and constant regulation. While vultures achieve sustained hyperacidity, crocodilians and pythons, achieve a rapid, episodic maximal acid production. The large meals of these reptiles require a massive, instantaneous digestive surge. To meet this challenge, pythons and crocodilians have evolved a specialised cardiovascular mechanism: circulatory bypasses that allow the heart to redirect CO2-rich venous blood directly to the stomach. This mechanism effectively increases the local concentration of the necessary components for acid generation. This evolutionary specialisation allows crocodilians to transition rapidly from a state of low acid output, conserving metabolic energy, to an acute surge of high-concentration acid production immediately following a large ingestion event. This adaptive regulation is crucial for the survival of these mega-carnivores, ensuring that the substantial energetic cost of extreme acidification is incurred only precisely when necessary for maximising digestion and disinfection.

Size matters, too. The vulture's digestive tract is notably short in proportion to body size. This strategy minimises the metabolic burden associated with maintaining a long intestinal tube. Studies of white-backed vultures show that the small intestine begins with a loop, measuring approximately 60 cm. This structural simplicity underscores an emphasis on speed and efficiency over protracted microbial digestion. The python's intestinal morphology is not static but highly plastic. During prolonged fasting, the gut is highly down-regulated, entering a state of functional atrophy to minimise the metabolic cost of maintaining a large digestive system. There is a dramatic change upon feeding, which begins rapidly upon ingestion. Within 24 to 48 hours, the python's small intestine undergoes a profound shift, rapidly converting from a shrunken, near-non-functioning state to a rebuilt structure capable of intense nutrient uptake. The absorptive surface area is exponentially increased, creating a vast temporary functional surface area. This morphological transformation translates directly into functional efficiency, resulting in a 20-fold increase in intestinal nutrient transport capacity within 48 hours. The system remains highly up-regulated for 10-14 days to process the bulk meal before returning to the quiescent state. The mechanism driving this powerful regeneration in pythons differs significantly from the continuous cell renewal typical of the mammalian intestine. Human intestinal cells are regularly renewed by activating stem cells located in the intestinal 'crypts'.

GETTING STUFFED

Gluttony, or consuming food far beyond physiological requirement, whether due to environmental factors, stress, or pathological reasons, introduces immediate strain on the human digestive system. The process begins with a failure of the body's satiety signals. It takes approximately 20 minutes for signals to travel from the stomach to the brain, indicating fullness. Gluttony bypasses the initial intestinal satiety phase, pushing consumption into the secondary gastric satiety phase, where eating continues until the stomach is physically full. The acute physical effects are immediate: overeating forces the stomach to expand significantly beyond its normal size, crowding adjacent organs and leading to profound abdominal discomfort, bloating, and fatigue. The excessive production of hydrochloric acid necessary to break down the massive meal can force reflux into the oesophagus, causing heartburn. Furthermore, the sudden caloric and nutrient load imposes metabolic stress, forcing all digestive and endocrine organs (including the pancreas and liver) to work harder to generate required hormones and enzymes.

Long-term gluttony forces the entire digestive system to perpetually operate at a heightened level, leading to pathological organ strain.

The human intestine's topography is established during foetal development through predictable phases of looping and rotation. Significant elongation of the intestinal tube in a healthy adult is not a natural adaptive response to chronic caloric loading, unlike the python's regenerative cycle. Instead, the primary adaptive response in the mammalian small intestine to chronic nutrient surplus is functional and focused on maximising the existing surface area — estimated at 30 square metres. Therefore, the human gut adapts by enhancing the existing surface architecture, not by elongating the tube.

Long-term gluttony forces the entire digestive system to perpetually operate at a heightened level, leading to pathological organ strain. This sustained overwork is a key precursor to systemic metabolic disorders, including insulin resistance, high cholesterol, and type 2 diabetes. The fixed physical constraints of the human gastrointestinal tract also introduce severe risks in cases of extreme acute gluttony (binge-eating). The human gastrointestinal system is optimised for continuous steady input. When subjected to the massive, bulk loading patterns associated with gluttony, the fixed morphological structure and limited adult plasticity lead not to adaptive growth, but to chronic metabolic strain and acute mechanical failure.

The lesson for our guts, then, is to eat food, not carrion, and not too much.

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH