Seeing through the skin, with X-rays

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 03 issue 10 :: Nov 2024

The Nobel Prize-winning discovery that took the world by storm, even as its discoverer renounced the fame that followed.

Anna Bertha Ludwig was not happy. It was a Friday evening in Würzburg, Germany, in November 1895 and her husband had come late to dinner – only after the maid had knocked on his lab door several times (bit.ly/lab-knock). He was distracted and unusually quiet, and rushed back to his lab as soon as he had eaten.

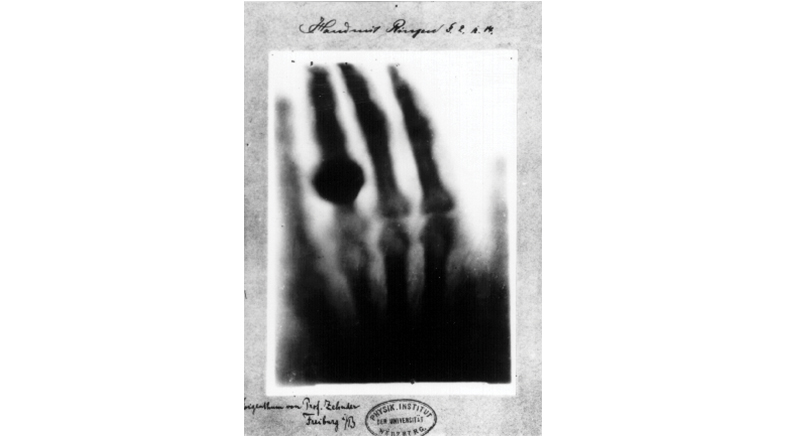

Over the next few weeks, his behaviour became more erratic – he didn't step out of his lab for food or sleep. When she asked him what was going on, he cryptically replied that if people knew what he was working on, they would say he had gone mad. Several weeks later, on the Sunday before Christmas, he finally took his increasingly worried wife down to his lab and asked her to place her left hand on a photographic plate for 15 minutes. To her shock, a shadow of the bones in her hand, with a black circle where her wedding ring was, appeared on the plate. Disturbed, she remarked: "I have seen my death."

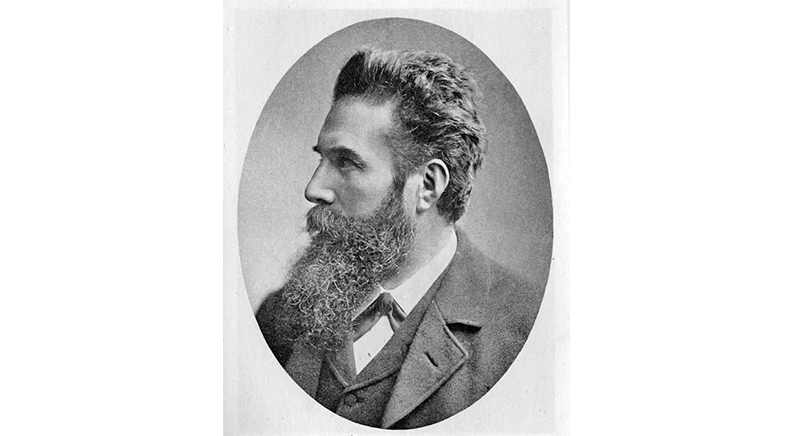

The ghostly image was created by mysterious rays that her husband, Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen (pictured), had discovered on that November night. When he had passed an electron beam inside a vacuum tube covered in black paper, his sharp eyes had caught a glow on a screen coated with chemicals far away from the tube. The discovery of this "new kind of invisible light" that he called X-rays, cemented his place in history and earned him the first Nobel Prize for Physics, in 1901.

TESLA'S 'SELFIE'

Thomas Edison and Nikola Tesla quickly built their own X-ray machines. Tesla apparently sent an X-ray photo of his own foot in a shoe to Röntgen with a letter of congratulations (bit.ly/Tesla-foot). Edison and Tesla were also among the first to sound the alarm about the dangerous effects of excessive exposure to X-rays.

When news of the discovery broke, some dismissed it as a hoax, despite the meticulous photographs that Röntgen had taken and published. The Standard tried to reassure its readers that it was "no joke" but "a serious discovery by a serious German Professor". Initial fears about invasion of privacy soon turned to fascination as people rushed to take X-ray images of themselves at shoe stores and carnivals (bit.ly/Discovery-X). X-ray photos helped solve murder cases, locate and fix broken bones, and identify people who had perished in fires. Military doctors found X-rays helpful in removing bullets and shrapnel from wounded soldiers. Physicist-chemist Marie Curie even designed X-ray ambulances that could be driven to the frontlines (bit.ly/Curie-units).

LENARD'S RANCOUR

Röntgen's fame rankled Philipp Lenard (pictured), who, like others before, had noticed the fluorescent glow caused by cathode rays but had not investigated them like Röntgen had. Adding fuel to the fire was that Röntgen had used one of Lenard's tubes for his experiments. Unhappy at being overlooked for the first Nobel – though he received one later – Lenard continued criticising Röntgen for many years (nyti.ms/4ha3XxR).

PHOTO: WIKICOMMONS

News of the discovery was dismissed as a hoax despite the many photographs that Röntgen had taken.

As for the Würzburg couple, their newfound fame upended their "quiet home life" (bit.ly/Discovery-fallout). Röntgen was a reticent person – he once set up a private lab space he could escape to when unwanted guests walked into his office. He was not happy with the sensational news coverage, remarking to his assistant once that he was "disgusted with the business". He spoke about his work only twice in public, skipped his Nobel lecture, and donated his winnings to the University of Würzburg where he worked (bit.ly/Nobel-donation). In his will, he asked for most of his lab notes and papers to be burned after his death. Despite a hefty inheritance, he lost a lot of money after the First World War. When his wife fell ill with kidney disease, he took care of her until her death, before dying of colon cancer a few years later in 1923.

Ranjini Raghunath is a Bengaluru-based science writer and editor.

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH