The universe according to James Peebles

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 03 issue 06 :: Jul 2024

The standard cosmological model is incomplete, but doesn't need to be overthrown, reasons Nobel Laureate James Peebles.

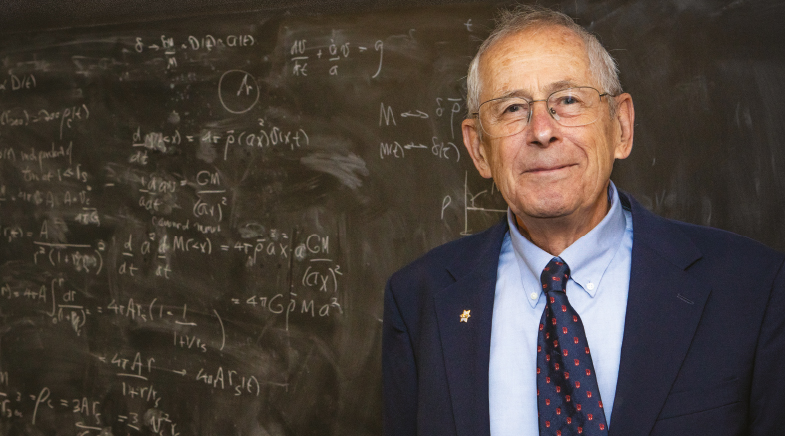

When P. James Peebles received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2019 "for theoretical discoveries in physical cosmology", he described himself as having been, in his early years, "just a dreamer, little motivated to do more than what was required to pass the examinations". Notwithstanding that self-effacing characterisation, Peebles is to this day acknowledged as a towering cosmologist whose contributions have hugely influenced and shaped theorists' ideas on the subject over decades. In a freewheeling interview to Shaastra, Peebles, 89, conveys a cosmic view of the field, and responds to the recent challenges to the standard cosmological model, of which he is the key architect. Excerpts:

What were the main influences that drew you to cosmology?

I was fortunate as an undergraduate to have had Ken Standing as Professor of Physics at the University of Manitoba. He taught me a lot and directed me to Princeton University for graduate study. I came to Princeton University with high ideas about being a theorist. In those days, particle physics was just starting to blossom. I was not very suited for that – but to my great fortune, Professor Bob Dicke (Robert Henry Dicke) took me under his wing. He was a brilliant experimentalist, and was doing work that attracted me: it was a study that led to astronomy, where gravity is important, which of course led to cosmology. So, I got into cosmology mainly because Dicke invited me to do it.

I should also say that not only am I not suited to be an elementary particle physicist, I am not an experimentalist. My talents lie in between. And it turned out that what was needed in cosmology then was someone like me. This happened around 1964.

I was (initially) reluctant because cosmology in those days was very slim... very little empirical evidence, highly speculative. I followed Dicke's advice and thought about it. There were lots of things to do, so I thought I'd write a few papers and then go on to do something meaningful.

I was deeply fortunate: I had arrived at the subject at the time it was ripe for more careful study. I recognised the opportunity and kept working in the field. For many years I was almost alone. As a post-doc, and a junior faculty member, I had the field almost all to myself. That's very rare.

What was the dominant mode of thinking in the field back then?

The dominant mode of thinking was that elementary particle physics was still much more interesting. Because it was growing, the concepts in particle physics were being developed. It was an exciting time. Cosmology was not an exciting subject because there was so little evidence, to improve or use what people had been doing. So, I did not have many influences. Dicke certainly encouraged me. But he was an experimentalist and had other things to do. So, he left me pretty much alone. People working on this field were very scarce. Fred Hoyle at the University of Cambridge was working on the steady state theory. It was never to my taste, and it never was very promising. David Layzer at Harvard University in the U.S. was also working in this field... (But) there were very few people.

"Both cosmology and particle physics have open questions... But in both cases, the main theory is not likely to be falsified by these anomalies."

The first major conference I went to had very few people – and I knew almost all the people in the field. Except the ones in the Soviet Union: they were doing work in parallel to what I was doing, but the communication was very poor... They managed to do great physics (in the Soviet Union), but were always hampered by the lack of communication.

So, I was not much influenced by anybody. I don't enjoy being influenced! (Laughs)

What would you tell students who take up cosmology today about the state of the field?

The field is now much more mature... there are far more people working in it, there are far more jobs – but there are a lot of people, too... The conditions of work have changed. Except for one or two exceptions, I have never joined a group of more than three people. It's very different today.

Now there are very exciting proposals that require very large number of people to work on very specific problems. If a research group is concentrating on a well-defined problem, they are not able to look at other issues. That is true of all human endeavours, isn't it? If you want something, you have to concentrate. But by concentrating, you lose a wider perspective of what might be interesting.

I guess in particle physics that's not a problem, because in the end it is a remarkably simple theory that could be worked out, its implications understood... Now they have the great problem of trying to unify... rather, it's crying for unification. But in cosmology, the world is so large that easily, there are fascinating things to be discovered, if only you know how to look for them. I have just finished the second paper on such a thing.

Would you describe it?

We are in a group of galaxies. It's called the local group. It has two major galaxies and dozens of smaller ones. They are distributed more or less in a plane – flat surface. They were called the local supercluster by Gérard de Vaucouleurs many years ago. Well established, but not well advertised, is that at greater distances, clusters of galaxies tend to be close to this plane. It's a startling thing. Hundreds of megaparsecs away, the clusters still like to be near this flat plane. This is a surprising thing that has been known at least since the 1980s, but has never been discussed by those who study modern cosmology and modern methods. Isn't that curious? It's a result of the fact that they had to concentrate and so they didn't look around.

The universe is full of surprises. Planets with wonderfully low densities were discovered by accident. Of course, there is the origin of life – very difficult to study. There are nearby stars with planets that can be probed, people are probing these. There are so many planets with many different properties. Clever ideas about what to look for may be revealing something.

So, my message is: keep your day job! My advice would be: pause on occasion to think about what might be interesting to do other than what you're doing. But keep your day job.

New missions have made possible observations that have given rise to tensions in the standard cosmological model. Which among these seriously challenge the model?

I must first explain my line of thinking on this. Each one of our physical theories, no matter how well-tested and firmly established, is incomplete... For each of our theories, you can ask questions which they fail to answer. Both cosmology and particle physics have open questions – curiosities, puzzles. We have more anomalies than particle physics does. But in both cases, the main theory is not likely to be overthrown or falsified by these anomalies. That is because we have tests that the theory passes that are pretty convincing that this is going in the right direction – in particle physics and in cosmology.

But cosmology is not complete. It means there is a better theory that would do better to resolve the anomalies that we have. It's a good bet also that when this new theory is found and the anomalies are resolved, there will be new anomalies. This has been the history of science ever since Copernicus moved the Earth from the centre of the universe. Great discoveries solve problems and give us new ones. That's the rule.

"The failure is only of the cosmological principle as it is defined by some people. Other people have far more lucid definitions, and the principle is not violated."

So, in my opinion, I think the anomalies are interesting because they guide us to a better theory... The likely situation is that the present theory will get adjusted, will get better. It's happened many times before.

Professor (Subir) Sarkar of Oxford University... has been talking to you (The cosmic rush) about the failure of the cosmological principle. I disagree with him on that failure. Because he defines the cosmological principle in a different way. Others do not. In fact, the cosmological principle is no longer the subject of interest...

Just to review, a century ago, Albert Einstein had decided that the only rational way to understand gravity is his new theory, General Relativity. He also decided that the only logical universe is one that is uniform: that is, same in all directions and distances, except the small fluctuations that you and I represent. He had no evidence for that. In fact, he was in close contact with a great astronomer, Willem de Sitter, who told Einstein that this picture did not at all agree with what astronomers know about the distribution of matter around us. De Sitter was quite blunt in his letters to Einstein. And yet, Einstein's idea was so simple and elegant that people were attracted to it. That idea was named the cosmological principle. It wasn't a principle, it was, on Einstein's behalf, a guess.

Similarly, my take is that the cosmological principle is not really a principle, it is an assumption. It is an assumption that in the large, the universe is quite close to uniform, in all directions, all distances. Remember, I am saying close to – there is no statement, there should never be a statement, that the universe is exactly homogeneous because it isn't.

He (Sarkar) and quite a few others studying this evidence say that the large-scale distribution of matter doesn't average out to be uniform in very large scales. It's probably true. But it only violates the cosmological principle if you assume that the principle says (that) at large scales the universe is exactly homogeneous. That is the definition he is using... The failure is only of the cosmological principle as it is defined by some people. Other people have far more lucid definitions, and the principle is not violated.

If you tell people who work in cosmology that their theory is seriously challenged, they are apt to be defensive. But the standard theory is not challenged by the observations of Sarkar and others yet, (because) we don't know what this theory predicts.

Which of the several anomalies proposed is your favourite?

You don't like to be asked which of your children is your favourite. It's the same with anomalies. They're all interesting and different. Some are more convincing than others. I believe they're important because they promise to lead us to a better theory.

"I do not consider cosmology as an exception in its beauty. All of nature is beautiful – on small and large scales. Look around the world, enjoy yourself."

And what is that route?

I have no idea... Of course, if you're doing research, it's because you don't know what you're doing – in a deep sense. So, keep studying these anomalies with an intention of seeing how they can guide us to a better theory. There's not a lot of success, I must say, but it's early days. And the anomalies are highly variable, very different. And not all are celebrated as much as they should be. An anomaly that is really at the heart of our subject is that we have a well-tested theory of the way the world is on very small scales. That's particle physics. We have a wonderfully successful theory, despite the anomalies, of the universe on large scales. That's cosmology. The two do not naturally join together. It's a very curious situation that the theories that are so successful are so different. To me there's only one serious problem with the evidence caused by the existence of two theories that are different. Isn't that neat? We should celebrate it. Young people should pay attention to this and other anomalies.

Seeing the world as a cosmologist, what is the message to our readers?

It is deeply impressive, deeply wonderful. That is true, looking around, seeing a tree or people, or mountains, or planets or other stars or galaxies. The world is a wonderful place. It can be fascinating to explore, simply for its own interest. But also, because of the fact that you learn how to do things to benefit society. We need all the help we can get on that score.

Can I make a personal remark? Perhaps you have noticed students walking around with cell phones... on our beautiful campus... I hope fashions will change again, and cell phones will fall out of style.

I do not consider cosmology as an exception in its beauty. All of nature is beautiful – on small and large scales. Look around the world, enjoy yourself.

See also:

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH