Fossil sheds light on early Earth

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 04 issue 08 :: Sep 2025

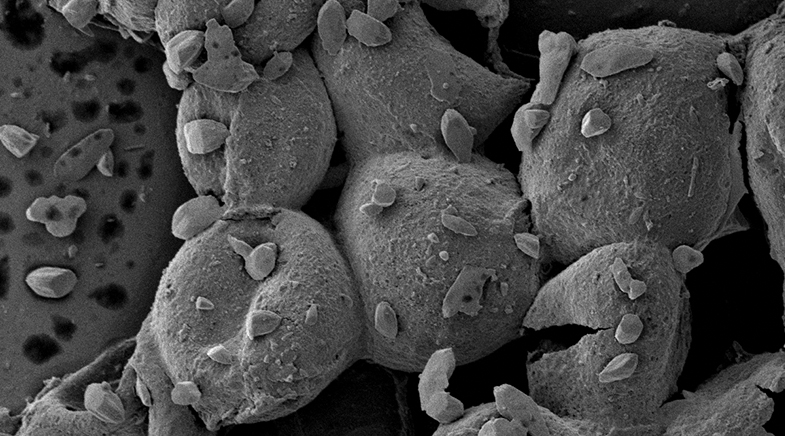

Traces of microorganisms believed to be 2.85 billion years old may shed light on a matter of abiding interest — the evolution of Earth. A collaborative research team led by Arif Husain Ansari, a scientist at the Birbal Sahni Institute of Palaeosciences (BSIP), found the traces buried under rocks in Madhya Pradesh's Baraitha-Girar region. The tiny spherical fossils, preserved in banded iron formations (BIFs), resemble the Huroniospora, the primordial microbe that once floated in the Earth's oxygen-starved oceans. These may be among the oldest known life forms on the planet (bit.ly/microfossils-mp).

Ansari was initially sceptical about the find because the Baraitha-Girar region is tectonically active. Tectonic deformation generates heat and friction that usually destroy such delicate structures. "When we processed the samples, we found remarkably well-preserved coccoid microfossils — small, spherical, colony-forming cells resembling bacteria," Ansari says.

The researchers eliminated all chances of contamination. First, they dissolved the collected rock samples in acid, leaving behind only the organic residue. To double-check, they cut wafer-thin slices of the rock. They found the same microscopic structures layer after layer, which indicated the fossils had indeed been locked inside the stone for millennia.

Instead of using water as plants or cyanobacteria do, these microbes used iron in their metabolism to generate energy.

The study suggests that these microbes were likely thriving on an oxygen-free Earth 2.85 billion years ago. Instead of using water as plants or cyanobacteria do, these microbes used iron in their metabolism to generate energy. "We think these organisms were anaerobic photo-synthesisers," Ansari says. They lived in association with the banded iron formations, where iron was being oxidised from ferrous to a ferric form. The research suggests a close link between microbial metabolism and iron deposition. In other words, life and Earth's geochemical cycles were already deeply connected at that time.

Usually, very ancient microfossils are visible only in thin sections and are often deformed. These microfossils have survived for millions of years because the Girar's BIFs have a high amount of silica, which is an excellent preservative. Something trapped in silica can last for up to 4 billion years. "The findings are significant as they shed new light on ancient microbial life and early Earth conditions," says Sunil Bajpai, a palaeontologist at the Indian Institute of Technology, Roorkee. "These are among the best-preserved Archean microfossils ever reported," Ansari points out.

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH