Worth its weight in gold

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 05 issue 01 :: Jan 2026

Fighting climate change with sunlight-generated hot electrons.

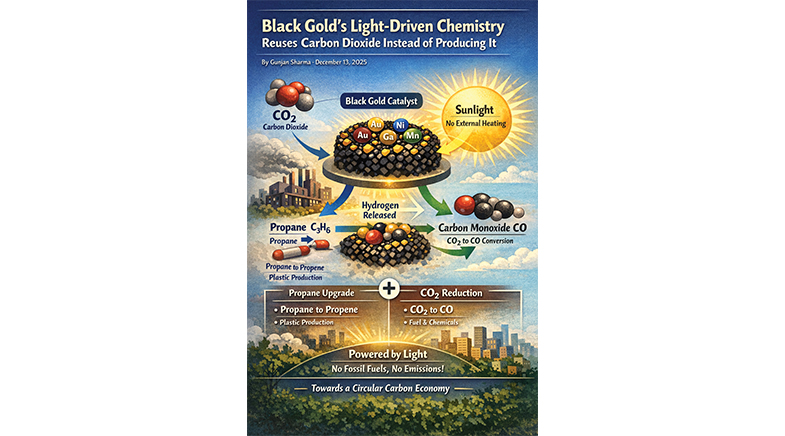

Converting carbon dioxide (CO2) into useful chemicals is recognised as an ideal way to combat climate change. But this process — called CO2 hydrogenation — is expensive and carbon-intensive as it needs a constant supply of hydrogen and high energy inputs.

About three years ago, researchers from Belgium showed that hydrogen could be readily produced if the CO2 reduction reaction was coupled with propylene production, one of the largest industrial chemical processes in the world. The propane needed for propene conversion, the first step in propylene production, releases hydrogen during the reaction, which can be harnessed for CO2 reduction to produce carbon monoxide (CO2), a valuable platform chemical used for making a variety of beneficial chemicals, including syngas. The conversion of one propane molecule to one propene molecule releases one hydrogen molecule, which can be utilised by CO2.

While combining these two chemical reactions appealed to many because of the circular route it provided for CO2 utilisation, it was not devoid of problems. Thermal catalysts conventionally used require harsh operating conditions (above 550°C), which, in turn, can trigger undesired side reactions, such as coke formation and rapid deactivation.

While conventional wisdom holds that these reactions cannot be carried out at low temperatures without compromising performance or stability, a team of chemists at the Mumbai-based Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR) has shown that they can. In a recent study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (bit.ly/New-Class), the TIFR team led by Vivek Polshettiwar, Professor of Chemistry, reported a new class of light-activated catalysts. "Instead of extreme heating, we harness sunlight-generated hot electrons to drive the chemistry," says Polshettiwar.

These catalysts are called plasmonic nanocatalysts because they are activated by plasmons, the collective quantised oscillations of free electrons in certain types of metals such as gold. The scientists synthesised the plasmonic nanocatalyst by loading small gold nanoparticles on fibrous nanosilica. The 'black gold' nanocatalyst thus derived was then spiked with nanoparticles of three different metals: gallium, nickel, and manganese. When these trimetallic active sites are present on the surface of the black gold nanocatalyst, it can produce propene and CO with high purity. The TIFR scientists ran the experiment continuously for 500 hours and established the catalyst's stability over a long period.

The TIFR team is now developing an ideal catalytic reactor design to enable upscaling for technology demonstration and eventual commercialisation.

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH