Blood, sweat and tears...

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 01 issue 04 :: Jul - Aug 2022

An accidental entrepreneur is saving lives with a 'smart bandage', made from shellfish waste, which arrests bleeding in quick time.

On a September morning in 2016, an Indian Army soldier, part of a platoon traversing a mountainside in Kashmir, stepped on a landmine. His leg was injured in the blast, and he was bleeding. It was a serious setback for the platoon, which was returning from a top-secret mission: a 'surgical strike' on alleged terrorist camps in Pakistan-occupied territories across the Line of Control. Returning home before the Pakistan Army was alerted was as much an imperative as saving the wounded soldier.

What saved the soldiers' day, going by their post-facto accounts, was a thin, dry, yellowish, rectangular patch of material that, when applied to wounds, arrests bleeding and facilitates clotting in double-quick time. That same patch saves the lives of countless accident victims in hospitals around the world – and even on the warfront in Ukraine.

The scaly lifesaver material with pores may look like a commonplace bandage, but medical experts reckon it's quite unlike any general dressing product. When applied to a wound, it can stop the bleeding within three minutes, faster than any available haemostat. And its secret ingredient is derived from a prawn or a crab.

Meet Axiostat, made out of shellfish waste.

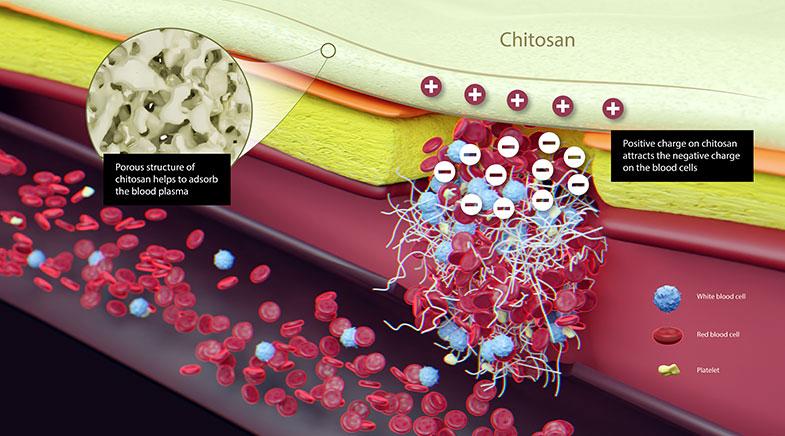

Developed by Bengaluru-based Axio Biosolutions, Axiostat is a stand-out scientific innovation. It is made using 100% chitosan, a polysaccharide found in shellfish extracts, which has a positive charge in an acidic environment. When chitosan is applied to a wound surface, the positive charge attracts the negatively charged red blood cell membrane, and accelerates clotting (see graphic).

However, it is not easy to extract chitosan or purify it. Producing a product with a five-year shelf-life on an industrial scale is even more challenging. Axio Biosolutions, founded in 2008, is the first Indian company to develop such a product using a patented process. Axiostat is now used in several large hospital chains in the country, the Indian military, as well as in 40-plus other countries and militaries.

"We've been using it (Axiostat) for two-three years for wound dressing. Chitosan can also prevent bacterial contamination," says Dr Rajesh Kesavan, a podiatrist (foot doctor) at Apollo Hospitals, Chennai. "The good thing about this is it can be cut, folded and applied onto any wound. The drawback: it cannot be used on dry wounds."

Kesavan points out that there are similar overseas products available in India, but Axiostat is more easily available, is less expensive – and acts immediately.

THE SCIENCE OF CLOTTING

"Blood clotting is a complex process," Leo Mavely, founder and CEO of Axio Biosolutions, says over a video call. "If the artery is sliced, it'll pump out blood – about 40 ml a minute. If bleeding continues for about 20 minutes, it could lead to death."

The phenomenon is called haemorrhagic shock, a condition of reduced tissue perfusion, resulting in the inadequate delivery of oxygen and nutrients necessary for cellular function. The body will try its best to stop the bleeding, by contracting vessels, sticking platelets to the damaged area and so on. But it is hard to induce this process manually in the event of uncontrolled bleeding.

When applied to a wound, Axiostat can stop bleeding within three minutes, faster than any available haemostat.

In India, road accidents account for an estimated 1.5 lakh deaths a year, a third of them from excessive bleeding, reckons a 2021 World Bank report. The numbers are even higher in the U.S. In the May 2022 mass shooting at a Texas school, almost 70% of the victims reportedly died of bleeding. Often, two minutes are all that separate life and death.

Mavely points to a critical consideration that gets overlooked: an amputee, with lower limbs severed in an accident, has a better shot at survival than someone with a nicked artery that is hard to reach.

Therefore, time is of the essence with bleeding injuries, which is where Axiostat scores. Its critical role in speeding up the clotting process and achieving haemostasis in under three minutes has been validated by at least four studies published in peer-reviewed journals: Indian Journal of Emergency Medicine; International Journal of Toxicology – Mechanism and Methods; International Journal of Oral Health and Medical Research; and The Journal of Contemporary Dental Practice.

WEALTH FROM WASTE

Not only is Axiostat a lifesaver, it additionally addresses a big environmental concern: the final disposal of crab or shrimp waste. Typically, after the meat is consumed, seafood shells are thrown away as waste. Of the 8.3 metric tonnes of shrimp produced in India, 2.5 metric tonnes end up as waste, according to an industry estimate from 2020. And shellfish production is increasing across the world.

However, if this hard, flaky animal cartilage is converted into chitosan, it literally generates wealth from waste: a kilogram of purified chitosan can fetch ₹50,000, given its unique properties. It is positively charged in an acidic environment, whereas most other polysaccharides are negative or neutral. Hence, it bonds with other negatively charged polymers. For instance, it can be used to soak up metals; it is biocompatible, non-toxic, low allergenic and biodegradable. For all these reasons, it is used variously: as a dietary supplement in the food industry, and as a chemical in effluent and sewage treatment.

Chitosan is the world's second-most abundant polysaccharide (next only to cellulose). However, owing to the rigour of extracting and purifying chitosan, it remains underutilised, especially in the biomedical and pharmaceutical industry.

The main raw material for chitosan production is chitin, found mainly on the shells of crabs and shrimps. Typically, the shells are grouped by size and species, and cleaned, dried and ground into pieces. Then they are purified; that process involves demineralisation, deproteinisation and decolourisation.

There is no standard purification process: different chitin sources require different treatments, given the diversity in their structures. Conventionally, it can be carried out using chemical or biological methods. The quality of chitosan depends on the source of chitin and its method of isolation. Chitosan will not dissolve in water, only in acid, which makes it hard to extract. The purity of chitosan is important, especially when used in medical products, since residual proteins can cause side effects. Axiostat is made entirely using purified chitosan at an industrial scale.

ACCIDENTAL ENTREPRENEUR

Over the years, Axio Biosolutions has raised over $20 million from a clutch of investors: the University of California–Ratan Tata Fund (UC-RNT Fund), TrueScale Capital, Omidyar Network India, and Accel. Mavely is discreet about discussing Axio's revenues: he will only acknowledge that Axiostat and MaxioCel (another Axio product for advanced wound-healing) currently account for revenues of "a few million dollars". Over one million units of the two products have been shipped to 40-plus countries.

Mavely is a first-generation entrepreneur: his parents are both retired bankers. What planted an entrepreneurial idea in his head, and set him on that path, was a dramatic – and blood-soaked – incident in his life.

In 2004, drawn by the buzz around Biocon Ltd's blockbuster listing, Mavely relocated from Kerala to Delhi to study biotechnology. Commuting from his South Delhi home to college on his motorbike, he would frequently come upon road accident victims. Along with his friends, he would take the victims to hospital, he recalls.

"One day, in 2007, while we were carrying a victim with head injuries to the hospital, I used my jacket to try and arrest his bleeding, but it just wouldn't stop. My jacket was fully soaked with blood, which was oozing out of his ears... By the time we reached the hospital, I almost fainted: I'd never seen so much blood in my life."

That's when Mavely realised there wasn't any product in India to stop such bleeding. He recalled that in college, he had read about chitosan's blood-coagulating properties as a biopolymer. Brimming with youthful exuberance, he reckoned he could somehow commercialise this idea. "I pitched it to Nirmalabs technology incubator, and it was selected," he says.

Nirmalabs, set up by technopreneur Madhu Mehta, was offering to groom and fund start-ups to the tune of ₹20 lakh if they could convert a promising scientific idea into a strong business plan. "My mentors were supportive of my idea, which they said would be impactful," recalls Mavely. That's how it all started.

PEER LEARNING TO PATENT

Serendipitous luck favoured Mavely in his early days. Given the difficulty in extracting chitosan, only a few companies were manufacturing it in India. However, an aqua biologist from Europe, who had set up his base in Gujarat and was conducting his own studies on chitosan, supplied Mavely with some batches of shellfish.

His next challenge was to figure out which acid would dissolve the chitosan. He devoured research papers, and scoured online patent resource databases, particularly freepatentsonline.com, for ideas. On that portal, he would look up research on similar topics, and take cues from the experience of others, and replicate their ideas – and improve on them. YouTube tutorials also opened the doors to peer learning for him.

Fusing all these learnings, Mavely developed a way to extract and purify the polymer from the shellfish. But he ran into his next problem: since it was a hygroscopic polymer, it would absorb moisture, which would diminish its potency. It therefore had to be packed in a way that it would not absorb moisture. One other consideration: Mavely wanted the product to be affordable, so he had to make it into a sheet form, with the minimum amount of raw material and maximum output. But the originally extracted polymer was in the form of powder flakes.

After many consultations with scientists and trial-and-error tweaks, he developed a process to take away the moisture, with a design hack of a method used by the packaged food industry. "The food that NASA takes to space is freeze-dried. In the absence of moisture, it will last longer. We use a modified form of that," says Mavely. "This is essentially sublimation: transforming ice to gas, bypassing the liquid stage. What is left is a moisture-less polymer layer. This is processed in an 'ISO 7 clean room', or a medical device-grade clean room. It is then sterilised using gamma radiation before shipping."

Mavely recounts with gratitude the generosity of corporates in helping him through this process. An imported freeze-drying equipment would have cost about ₹2 crore, which was beyond his capability. Flashing his 'student' credentials, he asked to use the lab of a Gujarat-based multinational pharmaceutical company, and the team there readily agreed.

FROM LAB TO MARKET

After the tests, Mavely secured a patent in 2011. But he still had to overcome the test of the marketplace. Demonstrating capability at lab scale was one thing; making a commercially viable medical product was entirely different. In particular, to secure regulatory approval, he had to overcome bureaucratic inertia at the office of the Central Drugs Standard Control Organization.

For four months in 2009, he would travel from Gujarat to Delhi every week, knock on the doors of babudom, and jump through many hoops. But the licence proved hard to get. Eventually, his luck turned. A newly appointed State Drug Commissioner held a face-to-face meeting with new start-up founders in Ahmedabad. It was a feel-good meeting, where all the speakers spoke glowingly of the government's initiatives. "I was very angry. I stood up and, sobbing and snivelling, spoke about my experience of trying to get regulatory approval," recalls Mavely. The tears were enough to wash away any residual bureaucratic inertia. The new Commissioner asked Mavely to come to his office the next day "to figure out a solution" – and sure enough, the very next day, his approval was on track.

Axiostat additionally addresses a big environmental concern: the final disposal of crab or shrimp waste.

Axio's first major fund infusion came when the newly opened Gujarat Venture Finance Limited (GVFL) made an equity investment of ₹1 crore in the company. (Axio would buy out GVFL in 2017, paying seven times as much!) The company received a few other grants; in 2012, it was picked for the 'Samsung Social Innovation Quotient', a televised start-up event.

Even after establishing the company, the learnings did not stop for Mavely. "While we were testing, we developed the technology at a lab scale. Later, we scaled it. That tech transfer was tricky. Entire batches can go to waste, and lead to big losses, in the event of, say, a power failure," he notes.

"When we went for trials— two in India, one in the U.S. and one in Europe — three out of the four failed. We realised then that outsourcing manufacturing put us at others' mercy," Mavely says. It took him nearly a year to figure out the tech transfer, and in that period, he had to rebuild the company from scratch. "For about a year, we were just making equipment, identifying faults, and making it again," he adds.

The effort helped him understand the manufacturing depth across Indian cities. In Coimbatore, Pune, Hyderabad, Vadodara, and elsewhere, engineers customised machines to match Axio's needs – at a fraction of what it would have cost in Germany, and the certainty of quality, which is sometimes suspect with made-in-China merchandise.

It has taken a lot of blood, sweat, toil and tears – literally – for Axio to get where it has, but today, Mavely looks to the future with confidence.

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH