The chips are up!

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 01 edition 01 :: May - Jun 2021

After several false starts over the decades, the semiconductor industry in India awaits a new dawn – and a fabless future!

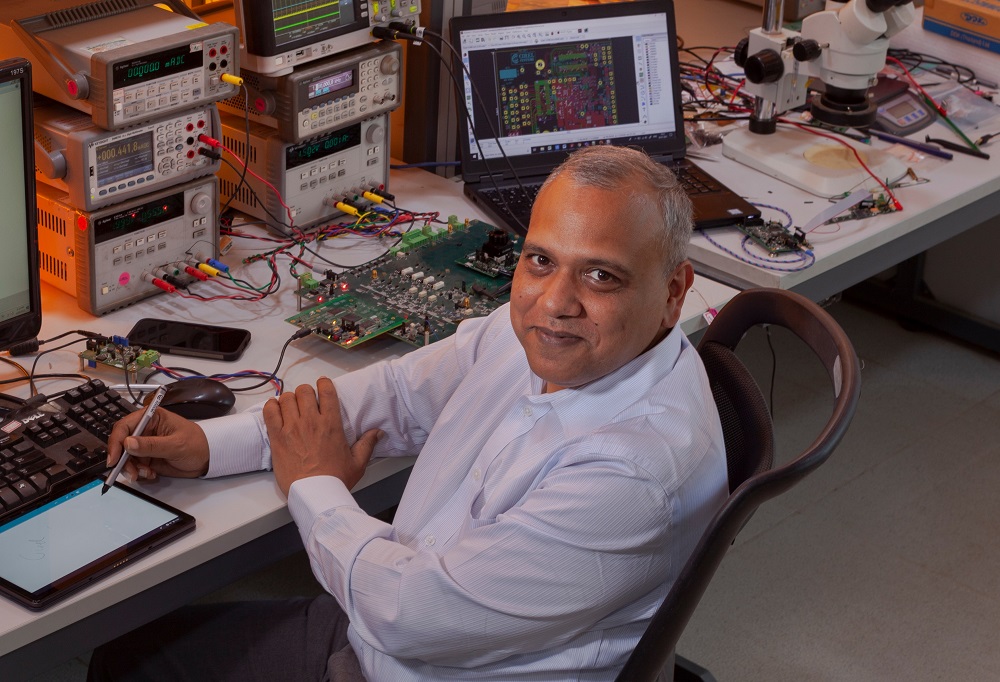

SRINATH Sridharan, Shyam Somayajula and Kishore Ganti came to Bengaluru from the U.S. in 2006 to set up a development centre for Silicon Labs. They had advanced degrees in computer science and significant experience at senior engineering positions in prominent multinational companies abroad. As they began work on the centre, they also started thinking about setting up their own venture.

They had studied in India for their undergraduate degrees, knew the semiconductor industry well, and wanted to bring their expertise to a home-grown venture. The three friends founded Aura Semiconductor in 2010. They had novel ideas about Integrated Circuit (IC) design, but they focussed on services and intellectual property (IP) in the early days of the company, spending most of their energy on building an engineering team and working towards their first round of funding. Within a few years, the company had a top-class engineering team. After they raised $6 million from WRVI Capital in 2016, the team started thinking seriously about building products. Two years ago, Aura launched its own ICs, one for mobile phones and the other for 4G and 5G infrastructure, both built using Taiwanese fabs. One of the chips didn’t sell as well as had been hoped, but the company had been noticed by venture capitalists and industry veterans.

In 2018, a Chinese private equity firm picked up a majority stake in Aura, opening up a new market for the company. A series of Aura products for the Chinese market followed in rapid succession. So far, it has designed 12 chips and shipped 20 million of them, and is on the way to launching ten more this year. Within a few years, Aura had gone from being a small IP and services company to becoming one of the most watched semiconductor companies in India. “Once you have market and consumer access,” says Ganti, “the IC definitions just keep flowing.”

HEAPS OF CHIPS

Aura’s sudden change in fortunes has been accompanied by increased activity in a few other companies, all Bengaluru-based, that have also launched their own chips – even if not so spectacularly. Cirel Systems has shipped 50 million chips cumulatively in its eight-year history. Saankhya Labs launched two products: a software-defined radio platform and another aimed at mobile devices, broadcast TV and satellite communications. Steradian Semiconductors developed radar transceiver chips for the automotive market, a difficult industry to crack. SignalChip launched four products, including a chip for 4G, LTE and 5G modems, in the past two years.

After a long lull, the fabless semiconductor industry has seen a few start-ups, including the likes of InCore Semiconductors, Kalatronics Semiconductors and LightspeedAI Labs. Meanwhile, two major Indian Institutes of Technology (IIT) had been developing their own chips. In 2019, IIT Bombay developed a processor, called AJIT, with funding from the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) and technical help from the private design automation firm Powai Labs. Last year, IIT Madras developed SHAKTI, an open-source processor fabricated at a foundry in Chandigarh owned by the Department of Space. Putting it all together, some industry observers now feel that semiconductor industry in India is about to turn a corner.

In reality, these are small steps for a country that seemed poised to become a big player in the semiconductor industry a decade ago, just before the time Aura was set up. By then India had seen two decades of semiconductor development in multinational research and development centres, which created a large pool of skilled engineers in Bengaluru and other cities. Some of these engineers had started moving out of the multinational centres and setting up companies early in the century. In 2007, the Indian government had, in its semiconductor policy, mulled setting up a fab in India; the Indian semiconductor industry seemed set to take off sometime during the next decade.

A FALSE DAWN

It didn’t happen as expected, although there were a few small successes. One of them was Cosmic Circuits, a product company set up in 2005 by Ganapathy Subramaniam, an engineer from Texas Instruments (TI India). Cosmic was the first Indian company to focus exclusively on products, and it developed analog and mixed-signal chips for analog-to-digital converters, temperature sensors, audio codecs and so on. When Cosmic was acquired in 2013 by Cadence Design Systems for $70 million, the Indian semiconductor industry saw a rare acquisition. The only previous acquisition of significance was of Armedia, a digital video IC firm, by Broadcom in 1999 for $67 million.

Although Indian observers expected start-ups and acquisitions to happen at regular intervals after that, they never did. The global semiconductor industry had been going through a difficult period in that decade. As semiconductor companies made chips at smaller and smaller dimensions, their capital costs went up steeply. It was hard to form a start-up and succeed in the business, even if the founders had original ideas, because the money needed to break into the market was too high. A start-up could raise $20 million and yet not have enough money to bring its products to the market.

Indian companies found it hard to thrive in this situation. Semiconductor design is a hard job, requiring domain expertise, engineering skills – and quite some money. Although a pool of talented engineers had formed in India, the barriers to entry to the international market were high for Indian entrepreneurs. Even fabless chip design start-ups, which required significantly lower investments to set up, did not form in large numbers in the country. Things had in fact looked bleak for those who expected high-quality companies to emerge from India at regular intervals. However, by 2018, the world market had begun to change, bringing optimism to the industry.

Saankhya, with its semiconductors for various applications, has proved that it is possible to create fabless companies in India.

A FALSE DAWN

Indian companies found it hard to thrive in this situation. Semiconductor design is a hard job, requiring domain expertise, engineering skills – and quite some money. Although a pool of talented engineers had formed in India, the barriers to entry to the international market were high for Indian entrepreneurs. Even fabless chip design start-ups, which required significantly lower investments to set up, did not form in large numbers in the country. Things had in fact looked bleak for those who expected high-quality companies to emerge from India at regular intervals. However, by 2018, the world market had begun to change, bringing optimism to the industry.

A fabless policy in the works

India’s fabless design industry could get a boost with a national policy planned by MeitY to bring 50 fabless firms together to launch 100 ICs in five years. The intended investment is about ₹1,000 crore.

The IESA is working to enable it to support new and existing projects to be chosen based on the idea, technology, commercial viability and the team for support at seed and growth stages, according to Chairman Satya Gupta. IESA hopes to put together a ₹4,000-crore fabless seed fund as well.

“The IESA initiative is welcome. The first utilisation of this funding should be to change the mindset to enable product-like thinking and activity,” said Manju Hegde, CEO of Texas-based radar-on-chip startup Uhnder. Hegde, an IIT Bombay alumnus, previously co-founded chip firms Celox Networks and AGEIA Technologies, which developed part of their chips in India, just as Uhnder now does.

A critical mass of Indian fabless companies is now beginning to work in AI and ML, communications and computing, and are designing sophisticated systems. Areas that need strengthening are product conceptualisation, architecture and post tape-out activities leading to volume production and the business side of things.

Indian academia, on the other hand, has done well in analog and mixed-signal. “If the two technical competencies are combined with product marketing to create commercially viable global products, we will do well,” says Gupta.

IESA plans to set up a Silicon Valley chapter as a means of creating a freeway of exchange with the Indian semiconductor ecosystem. It will cover design centres, fabless start-ups and funding and, most importantly, will develop a strong connect with semiconductor leaders of Indian origin in the Valley. Indian firms have reached out to senior people of Indian origin as mentors and strategic advisors.

RIDING ON DATA, AI

The optimism was fuelled by two major changes: the rise of data centres, and Artificial Intelligence (AI). As data centres increased in number and sophistication, and storage moved to the cloud, companies needed cloud-related chips in large numbers. The use of AI and Machine Learning (ML) in a number of industries also drove the development of AI-related chips by start-ups.

Many start-ups in these sectors have raised significant funding and have high valuations. The most significant example is the Silicon-Valley-based SambaNova Systems, which builds platforms for running cloud-based data centre applications, and has raised $1 billion since it was set up in 2017. It includes a $676 million series D funding from investors led by SoftBank, at a valuation of $5 billion. In 2019, Intel acquired the three-year-old Israeli AI chip start-up Habana Labs for $2 billion. The U.K.-based Graphcore, set up in 2016, has so far raised $682 million and was valued at $2.8 billion in December 2020 when it raised $222 million.

Several other AI semiconductor start-ups have raised significant funding or been acquired at high valuations. High valuations are especially common in China, where semiconductor start-ups have been raising large amounts of money. In April 2021, the Chinese chipset firm Unisoc raised $814.6 million from a team of investors.

China is also the world’s largest and fastest-growing semiconductor market. According to the Semiconductor Industry Association, sales in the Chinese market were $151.1 billion in 2020, roughly 36% of the global market of $439 billion. In contrast, the Indian market was just $21 billion in 2019.

Faced with such a small domestic market, Indian companies struggled to design products. A semiconductor ecosystem did not develop in the country except in isolated pieces. In its early years, Aura did not find it easy to conceive products for specific markets. Once it raised funding, investors sensitised the company to the potential of the Chinese market and the company grew rapidly. However, it grew on a foundation built in the first half of its life. It had built a large team of skilled chip designers that a development centre in China supplemented. “Aura creates chips as good as any American company,” says Subramaniam, now a partner in WRVI Capital, which first invested in Aura.

Change happened slowly in the Indian market over two decades as companies learned to utilise their design expertise for the overseas market. Now some entrepreneurs are trying harder than ever to crack the overseas market. “India will open up as a market at some point, but it may be too late to enter it then,” says Ganti.

Focussing on chip design

India’s semiconductor industry is expanding incubation and mentoring initiatives to spur fabless design. The most significant of them is the Semiconductor Fabless Accelerator Lab (SFAL), Bengaluru, headed by Muthukrishnan Chinnasamy, who worked at TI India and has founded chip design firms.

“There are some 50,000 engineers in chip design in India. Harnessing their skills, we can build our own innovative designs,” Chinnasamy said.

SFAL, funded by the Karnataka government to boost fabless start-ups, has chosen 12 firms for incubation and mentoring and invested in four of them. Portfolio firms include Calligo Technologies, focussed on Big Data and AI; Kalatronics Semiconductors, which is into IP solutions for faster interconnect speeds; Morphing Machines, with its many-core, massively parallel, runtime reconfigurable embedded ICs; and LightspeedAI Labs.

For example, Prasad Panchangam, founder, Saigeware Technologies, a SFAL portfolio start-up developing IP for ICs, looks to SFAL for inexpensive access to prohibitively priced design tools. Such tools are important and, being expensive, difficult to access for start-ups.

The Fabless Chip Design Incubator (FabCI) at IIT Hyderabad, an incubation initiative that looks to create an ecosystem for chip design start-ups, includes Lemon Flip Solutions, which is developing ICs for military and other defence applications. FabCI helps with angel funding, design tools, prototyping and characterisation facilities, mentoring and foundry access.

Other similar though private initiatives are the Semiconductor Startup Incubation and Acceleration Program launched by Dutch chip firm NXP Semiconductors, in collaboration with MeitY and FabCI; and the Hubballi-based KLE Technological University’s Centre for Technology Innovation and Entrepreneurship, with SemiKsha Semiconductors being a portfolio start-up.

DESIGN EXPERTISE

India has over 50,000 designers working for multinational firms, and they provide a big pool of expertise for those who want to make sophisticated products.

Cirel Systems, for example, has been able to break through to the overseas markets rapidly in the past two years. Originally a business unit of Cosmic Circuits, it was spun off as a separate company after Cosmic was acquired by Cadence. Cirel had sold 20 million chips while being a division of Cosmic, and has since sold another 30 million as a separate company.

Cirel’s success is partly due to its having chosen a domain, the stylus, where it has become one of the world’s leading players. Cirel has had a sudden increase in business in the last one year, and remains one of the few – if not the only – company in the country that can make and ship chips in large volumes. “Though Cirel’s IC is small, it shows it is possible to create fabless companies in India,” says Subramaniam, also the company’s Chairman.

A few other companies too have demonstrated that. Saankhya, with its wireless technology and semiconductors for applications ranging from rural broadband to satellite communication, has solutions for 5G, including 5G broadcast. Other products include radio access network analytics support and a “dynamic cell edge detection” that helps interference management and modulate emitted power, techniques that improve both capacity and power consumption. One of its previous chips, Pruthvi-3, is a game-changer for the telecom and broadcasting industries by enabling convergence of the two.

Steradian, which has assembled a topnotch engineering team, is into cutting-edge imaging radar ICs fabricated at overseas foundries, and similar products aimed at the global automotive and industrial markets and applications ranging from traffic monitoring to indoor sensing.

THE NETWORK EFFECT

The stories of Cosmic, Saankhya and Steradian show how multinational centres spawn high tech companies in semiconductors. These companies, and indeed almost every fabless design firm in India, were either founded by former employees of TI India or have core teams from it. Saankhya has several engineers who have spent long periods in TI.

“In the late 1980s and ’90s, the TI leadership took pride in doing more and more complex chips from India. This, coupled with the fact that in those days they attracted very good talent, has led to TI individuals taking on not only entrepreneurial roles but senior roles in many other semiconductor companies,” says Cirel Chief Executive Officer Sumeet Mathur, who himself worked in TI India.

Indicatively, Sankalp Semiconductor, a fabless design firm that was acquired by HCL Technologies, was started up by Vivek Pawar, who had worked for years at TI India. So completely does TI India lord over the country’s fabless ecosystem that the Bengaluru-based fabless semiconductor consultancy EmuPro, with half a dozen clients, is headed by Anoop Dutta, himself an ex-TI India staffer.

Even beyond founders with roots traceable to TI India, new companies are still being formed, although at a slow pace, which has become a feature of India’s semiconductor industry. Some of these companies are indeed developing AI chips, the current trend in the industry around the world.

LightspeedAI Labs is developing an optoelectronic chip that uses light for computing. Alpha IC, a company set up in 2016, uses principles of AI for edge computing, a method of computing where the data is processed by the device and not the cloud, a rapidly rising market. InCore Semiconductors, a start-up with roots in IIT Madras, is also developing IP in AI.

High-end fabs are too costly to build in India. But there may be scope to build fabs making low-end chips in high volumes.

A FABLESS FUTURE

Although setting up a fab in India becomes increasingly difficult as technology advances, costs increase and little original equipment manufacturing continues, many observers feel that developing a large fabless semiconductor industry is not too difficult now. “That successful fabless product companies can be built without having indigenous fabs has been demonstrated by Qualcomm and Broadcom in the U.S.,” says Satya Gupta, Chairman, India Electronics and Semiconductor Association (IESA). In India, the recent successes of Cirel, Aura and Saankhya – although modest by international standards – suggest a fabless semiconductor industry has taken root and holds potential.

Although high-end fabs are too expensive to build in India, there may be an opportunity for building fabs that make low-end chips in high volumes. A large number of new devices are now being manufactured that require small chips in them, such as smart cards and highway tags. These may not be cutting-edge technology but have good business potential. India is yet to move in this direction, but observers believe a long-term plan can trigger rapid change.

For example, there is a good home market for semiconductors; semiconductor consumption in India was about $21 billion in 2019, growing at the rate of 15.1 per cent, according to IESA’s Electronic System Design and Manufacturing 2020 report done with business consulting firm Frost & Sullivan. It put the overall consumption of electronics components at $31 billion, with two-thirds of it accounted for by semiconductors.

“India does not have an indigenous original equipment manufacturing ecosystem that can source our chips,” said Saankhya CEO Parag Naik.

“India has been left behind in the electronics and semiconductor product market. It is imperative that we pursue both electronic products and semiconductor development vigorously,” said Ravi Thummarukudy, CEO, Mobiveil, California, and co-founder of chip design solutions firm GDA Technologies, later acquired by L&T Infotech.

Electronics production currently contributes 3.3% to the Indian economy and is expected to grow to $320 billion by 2025. However, new and additional measures give it the potential to reach as much as $410 billion, or 8.2% of India’s targeted economy size of $5 trillion, IESA said.

With semiconductor content in electronics rising and the use of electronics itself also on the rise, Indian fabless design firms cannot complain of the lack of a home market anymore. A national electronics mission is also believed to be in the works; perhaps, fabless design can get a boost from it.

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH