Guillain-Barré syndrome: a nervous breakdown

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 04 issue 02 :: Mar 2025

What we know so far about the rare neurological disorder that has triggered a health alarm in parts of India.

On February 4, 1976, David Lewis, a 19-year-old soldier at Fort Dix in New Jersey, fell quite ill with the flu, like many others at the U.S. army base. But instead of resting, he joined his unit on an overnight hike, during which he collapsed and later died. His autopsy confirmed what public health officials had suspected: his illness had been caused by a new strain of swine flu genetically similar to the one that had caused the devastating 1918 pandemic.

In response, President Gerald Ford swung into action, ordering that "every man, woman and child" in the U.S. be given the flu vaccine within months. But no cases were reported outside the base, and no other deaths. Ford's government, however, refused to backtrack, even agreeing to absorb any legal fallouts from pharma companies fast-tracking vaccine production.

What finally forced his hand was an alarming spurt in the number of vaccinated individuals developing Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS), a rare neurological disorder that left more than 400 people with muscle weakness and paralysis and several dead. Hundreds of lawsuits were filed against the government, and Ford lost his re-election bid in November. The vaccination programme was halted the following month.

Although the controversy brought GBS into sharp focus — prompting researchers to look closely at its link to vaccination and outline diagnostic criteria — it was not a new disorder at that time. And decades after the symptoms were first observed, GBS continues to be a cause for concern. India reported an outbreak in January-February 2025; at least 20 people are said to have died of complications arising out of GBS.

PERIPHERAL ATTACK

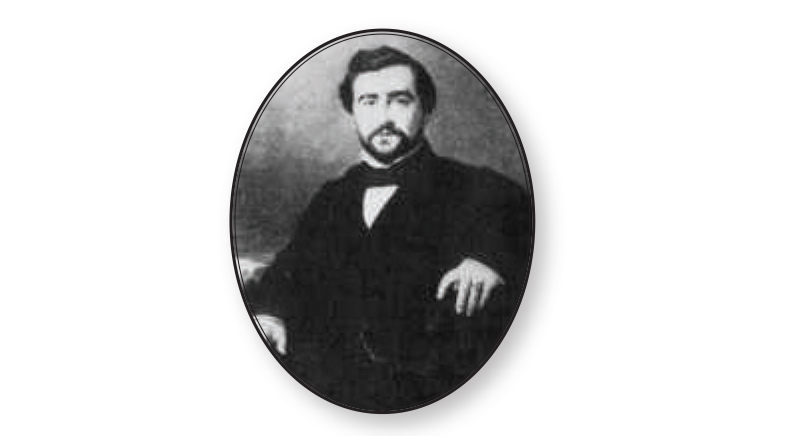

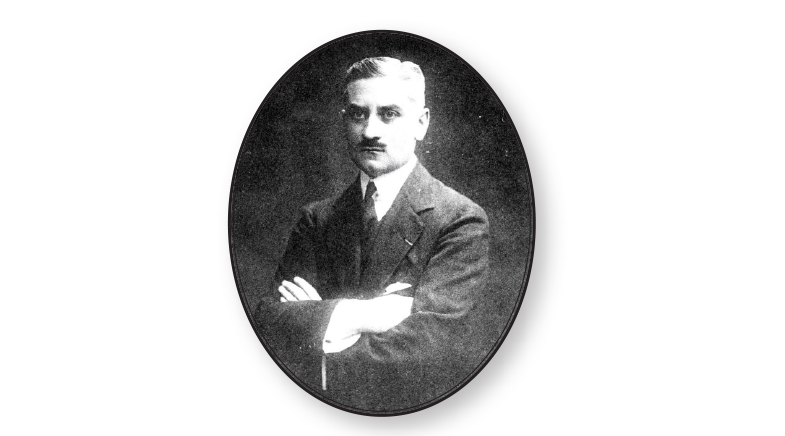

In 1859, French physician Jean Landry was the first to describe an "ascending paralysis" in a handful of patients, which started with the feet and moved up across the body. In 1916, at the height of the First World War, French physicians Georges Guillain, Jean Barre, and André Strohl noticed two soldiers developing tingling and weakness in their limbs, eventually losing sensation and movement. One of the soldiers fell when he tried to lift his backpack and could not get up. Using a lumbar puncture, the trio found that the soldiers had increased levels of proteins in their cerebrospinal fluid but no increase in the white blood cell count. The soldiers recovered unexpectedly after a few weeks. This disorder eventually came to be called Guillain-Barré syndrome (Strohl's name was unceremoniously dropped).

GBS affects the peripheral nervous system (PNS), the network of nerves that relays signals from the brain and spinal cord to various body parts and vice versa. It can impair both sensory neurons in the PNS that respond to touch and pain, and motor neurons that control movement. Long, thread-like extensions of these neurons called axons act like telephone cables linking one neuron to the next. Axons are wrapped in a protective fatty layer called the myelin sheath, which has gaps called nodes of Ranvier. Electrical signals hop rapidly from one node to the next across the length of the axon.

It is these axons that GBS targets, damaging either the myelin sheath (demyelinating GBS) or the axon itself (axonal GBS), short-circuiting their signals. This can lead to muscle weakness and loss of sensation. Some patients develop paralysis in the arms and legs and, in rare cases, in the lungs or the heart, putting them in intensive care or on ventilators.

In 1949, American scientists Webb Haymaker and James Kernohan delved deeper into GBS, noting that it caused inflammation at nerve roots and hinting at the possible involvement of the immune system. In 1969, a study led by American neurologist Arthur Asbury showed that even in early stages, "specifically-sensitized" immune cells were infiltrating and attacking the myelin sheath and causing inflammation. Asbury also helped define diagnostic criteria for GBS patients.

Today, scientists have a better understanding of the role the immune system plays in driving GBS, even if some pathways and players are still unknown. Something — in many cases, an infection — tricks the immune system into mistaking parts of the PNS for foreign agents and attacking them.

Depending on which part is attacked, GBS is classified into subtypes. The most common is Acute Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyneuropathy, in which antibodies produced by the immune system attack the myelin sheath. In 1956, Canadian neurologist Charles Miller Fisher noticed patients with weakness in the eye and facial muscles caused by damage to cranial nerves: this eponymous 'Miller Fisher syndrome' is now also considered a GBS subtype.

The most aggressive and recently identified subtype, Acute Motor and Sensory Axonal Neuropathy (AMSAN), attacks the axons of sensory and motor neurons directly, leading to poor recovery in patients. In AMSAN — and a related variant identified in China in the 1980s called Acute Motor Axonal Neuropathy (AMAN) — the main culprit seems to be rogue antibodies produced by the immune system that mistakenly attack the axon nodes (bit.ly/variant-AMAN). The antibodies home in on fatty molecules called gangliosides on the neuronal cell membrane, which play key roles in neuron growth, development, and regeneration. These anti-ganglioside antibodies also appear to lie at the heart of infection-driven GBS.

MOLECULAR MIMICRY

In the 1980s, studies reported that patients infected by the bacterium Campylobacter jejuni, one of the most common causes of food poisoning, developed GBS within days, and showed more severe axonal damage compared to other GBS triggers. A 2001 study (bit.ly/GBS-risk) suggested that patients with C. jejuni infection had a 100-fold increased risk of developing GBS. Experts think that this bacterium might be responsible for the ongoing outbreak in parts of India.

What causes such infections to trigger GBS? In 1989, Japanese researcher Nobuhiro Yuki observed that a GBS patient had watery diarrhoea a week before developing muscle weakness. On further investigation, Yuki and his colleagues spotted an increase in specific anti-ganglioside antibodies in such patients. Subsequently, they zeroed in on fatty molecules called lipo-oligosaccharides found on the cell membrane of some strains of C. jejuni. These molecules were so similar in structure to the neuronal gangliosides that antibodies produced by the immune system against the former also targeted the latter — a phenomenon called molecular mimicry. Many infectious bacteria and viruses, such as the Zika virus, seem to harbour surface proteins that resemble gangliosides or other neuronal surface proteins.

It is not fully clear what happens when the antibodies bind to neuronal gangliosides. However, some studies have shown that they turn on a cascade of immune reactions that disrupt ion channels at the nodes of Ranvier, causing injury to neurons.

Anti-ganglioside antibodies have been found in more than half of GBS patients and about 80% of those with axonal GBS. However, patients with demyelinating GBS don't seem to produce a lot of antibodies. This has prompted researchers to ask if other immune components might also be involved.

GBS affects the peripheral nervous system — the network of nerves that runs through the body and relays signals.

MISTAKEN IDENTITY

In 1955, American researchers Byron Waksman and Raymond Adams injected rabbits with extracts of specific nerve cells. In about two weeks, the rabbits developed muscle weakness and showed high protein levels in the cerebrospinal fluid, as well as heavy infiltration of immune cells into peripheral nerves and nerve roots. The animals provided a robust model that scientists use even today to mimic immune-mediated nerve inflammation and damage in GBS.

Using this animal model, scientists have found that immune cells called autoreactive T cells play a key role in damaging peripheral nerves, specifically in stripping them of their myelin sheaths. These aberrant T cells mistakenly target proteins normally present in the body. Recent studies have shown that in GBS, autoreactive T cells — produced in response to viral infections, in some cases — seem to target at least three specific proteins found on the myelin sheath (bit.ly/three-proteins). Some T cells trigger the production of antibodies and inflammatory cytokines (proteins) that attack neuronal proteins. Other types of T cells directly attack entities called Schwann cells that produce myelin, and break down the blood-nerve barrier, allowing other immune components to leak through and cause further damage.

Because the misbehaviour of immune system components is the underlying factor in GBS, researchers have tried to see if therapies that suppress it can help patients. For example, Intravenous Immunoglobulin therapy (IVIG), the current 'first line' treatment, involves injecting patients with purified antibodies from healthy donors. When given early, IVIG can dilute the number of rogue antibodies and clamp down on autoreactive T cells, protecting nerves from severe damage and allowing patients to recover.

In the century since GBS was first described, scientists have identified specific triggers, symptoms, subtypes, and therapies. Yet, there are still many unsolved mysteries. Not everyone exposed to the same trigger develops GBS; so, do genetic or environmental factors also play a role? Some patients recover soon, while others experience weakness and paralysis for months. At the heart of these mysteries lie many unknown players in the immune system whose roles are still murky. Given that the immune system is something of a Gordian knot, unravelling these is easier said than done.

Ranjini Raghunath is a Bengaluru-based science writer and editor.

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH