Old drugs, new hope

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 01 edition 03 :: Sep - Oct 2021

The world needs effective drugs to fight COVID-19, and Indian scientists are close to making a breakthrough with repurposed drugs.

Medicinal chemist Ram Vishwakarma has his fingers crossed. For more than a year now, the former Director of the Indian Institute of Integrative Medicine, the Jammu-based laboratory of the Council of Scientific & Industrial Research (CSIR-IIIM), has been on a mission. He seeks to help develop drugs that can save the country from a further onslaught of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which has so far caused over 234 million infections and 4.8 million deaths across the world.

Like many in the scientific community, he firmly believes that vaccines alone cannot help battle the pandemic. The world needs effective drugs that can bring down the severity of the illness, if not cure the infection completely.

Vishwakarma has pinned his hopes on Niclosamide, an anthelmintic drug first developed in the 1950s. An Aspirin derivative, Niclosamide was among the two dozen drug molecules that a COVID-19 strategy group at the CSIR had identified for screening and synthesised afresh in various CSIR labs as potential drugs early last year. "It came up on top during the screening along with a few other molecules," says Vishwakarma, who has been among those spearheading the CSIR initiative which was launched soon after the pandemic spread in the country last year.

His confidence in Niclosamide stems from two startling discoveries made in recent months by two groups of scientists - one in India and the other in the U.K. While researchers at the National Centre for Biological Sciences (NCBS) in Bengaluru for the first time showed that the drug could inhibit the virus's entry into the cells, their counterparts at King's College London found it could tackle inflammation and damage in lung cells. But both were laboratory studies.

Niclosamide was among the two dozen drug molecules that a COVID-19 strategy group at the CSIR had identified and synthesised afresh.

Apart from Niclosamide, there are at least three other repurposed drugs that are in clinical trials in India. These include antivirals Umifenovir and Molnupiravir and psychiatric drug Chlorpromazine.

EARLY MOVER

Much before the first wave of the pandemic hit India, CSIR had set up a COVID-19 strategy group to develop diagnostic kits and therapeutics for the infection as well to evolve a genomic surveillance mechanism to detect newly emerging mutants of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. While the other verticals found success early on, identifying drugs that are effective against the viral infection was understandably a relatively slow process.

To begin with, CSIR, which has a sound synthetic chemistry legacy, pulled together teams from its different constituent laboratories to synthesise drug molecules that could be potentially useful.

"As we realised that it was not possible to discover and develop new drugs, we decided to repurpose drugs based on the science that is available and also keeping the pathology of COVID-19 in mind. Based on our interactions with clinicians as well as scientists working on drug molecules, we identified around 25 molecules for synthesis," says Vishwakarma, who retired from CSIR-IIIM in June last year.

The molecules thus chosen were either approved the world over for other viruses or found to be useful in treating viral diseases in one way or the other, Vishwakarma explains. "Since we (CSIR) are very good in synthetic chemistry, we synthesised these drugs and kept them ready so that we had the drugs available to carry out clinical trials or if any of these drugs got approval elsewhere. If you remember, the supply chains were completely broken at that time as the world was in a shutdown mode," he adds.

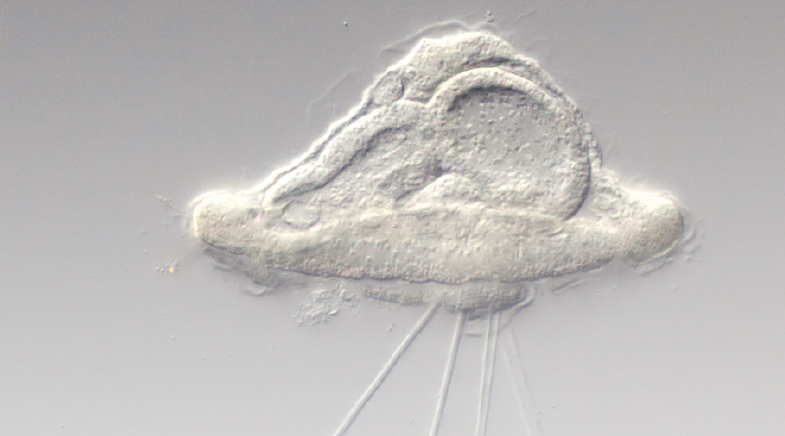

As these molecules were prepared, they scouted around to find researchers to test them in labs as well as in animal models. Among the labs that were put into use were NCBS and the Bengaluru-based Institute for Stem Cell Science and Regenerative Medicine (inStem). Their rich experience in cell biology helped the researchers figure out that Niclosamide had the ability to block the entry of the virus into the cytoplasm of the cells and thus would arrest its propensity to replicate.

"From our studies over two decades, we know that the cell acidifies the materials that it takes in and this acidic environment is what many viruses use to promote a fusion process which allows them to dump their 'payload' to the cytoplasm," says NCBS Director Satyajit Mayor, who led the research effort. "Among the bunch of molecules we screened we found that Niclosamide has the ability to short-circuit this acidification process. Nobody had identified it as an acidification inhibitor earlier."

Apart from Mayor's team, among those who significantly contributed to the study were research teams led by Varadharajan Sundaramurthy of the NCBS, Arjun Guha of inStem, and Vishwakarma.

Their study was first published in preprint server bioRxiv in December last year and subsequently in PLOS Pathogens in July this year. The first authors of these studies were doctoral students Chaitra Prabhakara, Rashmi Godbole, Parijat Sil and Shah-e-Jahan Gulzar, and post-doctoral fellow Sowmya Jahnavi from the NCBS.

"Our scientists were able to capitalise on their years of training and expertise and pivot to address the need of the hour. Without this investment over the years and the collaborative spirit, such an effort would have taken a lifetime to put together from scratch," Mayor stresses.

FINDINGS ELSEWHERE

Around the time the Bengaluru scientists cracked this, a team at King's College London led by eminent clinical microbiologist Mauro Giacca identified some unusual features in the lungs of people who had died of COVID-19. Autopsies carried out by them on 41 deceased patients found that, in many of them, cells that line the lungs were fused, leading to fluid accumulation, which had hampered breathing. They found that this fusion process was mediated by the spike protein that the virus used to gain entry into human cells. Giacca's team then found in lab studies that the Niclosamide molecule had the ability to prevent this cell fusion process called syncytia.

"Giacca got in touch with us subsequently, and while these studies are progressing we roped in a Hyderabad-based pharmaceutical firm, Laxai Life Sciences, which, jointly with the CSIR lab in Hyderabad - the Indian Institute of Chemical Technology (CSIR-IICT) - launched Phase 2 clinical trials of Niclosamide. The trials launched in June are progressing well," Vishwakarma, who is currently an advisor to the CSIR Director General, says.

CSIR-IICT is also carrying out trials on an old antipsychotic drug called Chlorpromazine, which is seen to be prophylactic against the infection, says Director Srivari Chandrasekhar, who heads the COVID-19 therapeutics vertical of the CSIR strategy group. "The clue about Chlorpromazine came from French researchers who had found that patients taking the drug were not getting COVID-19 even though the doctors treating them were COVID-19-positive," he says. "But as no one there was following this up, we thought we would," he adds.

Meanwhile, a consortium of a few Indian pharmaceutical firms, including Cipla, Dr Reddy's Laboratories, Sun Pharma, Natco Pharma and Hetero, are conducting clinical trials of Molnupiravir, an influenza drug originally developed by the U.S. pharma giant Merck. Merck already has a voluntary licensing agreement with a few Indian generic drug manufacturers to make the drug widely available if it is found to be effective against COVID-19.

"Molnupiravir has cleared Phase 2 trials in the U.S. But a consortium of Indian companies has done Phase 3 trials and recently submitted the data to the drug regulator," Chandrasekhar says.

"The drug is meant for mild and asymptomatic cases. But we are pushing it because if an asymptomatic person starts it the moment he or she is positive and prevents the infection from progressing to the moderate or severe stage, there is nothing like that," he observes. Molnupiravir was among the drugs for which novel synthetic processes were developed by the CSIR labs.

Another drug for which Phase 3 clinical trials are already over in the country is Umifenovir, also called Arbidol. The Lucknow-based CSIR lab Central Drug Research Institute (CSIR-CDRI), together with another CSIR lab, not only developed the process technology for the drug but also took it through clinical trials. "This could be one of the cheapest drugs available for treating mild and asymptomatic cases," CSIR-CDRI Director Tapas Kundu says.

The drug is being manufactured and marketed in India by the Goa-based Medizest Pharmaceuticals. "We have got very significant data. And we have already submitted it to the Drugs Controller General of India for approval," Kundu says.

Vishwakarma says that progress is also being seen in a drug called Colchicine. This is particularly beneficial for those who have cardiac problems. Used to treat gout and extracted from a plant called flame lily (Gloriosa superba), which farmers in Tamil Nadu commercially cultivate, Colchicine has been around for a long time. "India along with an African country is the biggest supplier of Colchicine, indicating its easy availability," Vishwakarma says.

The scientist foresees the use of a cocktail of drugs for COVID-19 management, similar to the one used for treating HIV. "We will need three or four molecules together that can slow down the growth of the virus and thus let the immune system clear it. Vaccines are there, but there is an uncertainty around them. Vaccines can save you from developing severe disease, but if you develop a severe disease you need a drug that can protect you," he says.

Also in the works is an ambitious antiviral therapeutics programme that the Central government is planning to launch. It is expected to be like a consortium, with those working on antivirals in any institute or university in the country coming together to develop new drugs for diseases caused by viruses. The scope of the programme is expected to go beyond SARS-CoV-2 but the details are still being worked out. It may be very similar to a $3-billion antiviral development strategy launched by the U.S. Administration in June even though the quantum of funding may vary, according to an expert who is privy to the development.

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH