For a sea change

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 04 issue 11 :: Dec 2025

Minerals from the ocean bed are luring explorers to its depths. But the red flags advise caution.

Come 2026, and the Carlsberg Ridge — a range of underwater mountains separating the Arabian Sea from the Somali Basin — is likely to see some hectic activity. India recently won a contract from the International Seabed Authority (ISA), an intergovernmental regulatory organisation, to explore an area of 10,000 square kilometres of the Ridge for polymetallic sulphides — compounds of rare minerals such as cobalt, zinc, gold and platinum, formed by the activity of hydrothermal vents or fissures on the seafloor. Researchers look upon this source of minerals as an alternative to fast-depleting supplies on the Earth's surface.

Contracts do not give explorers the right to exploit the ridges for minerals. The ISA is yet to frame the laws for deep-sea mining.

India is the only country to be given a contract so far to explore the Ridge. Formed at the triple junction of the African, Indian, and Australian plates, the Ridge extends right up to the Gulf of Aden, spanning an area of approximately 300,000 square kilometres. The peaks rise to over 2,000 metres above the seabed. This underwater world is seismologically active. Along plate junctions, there are fissures through which seawater seeps into the mantle. The water scavenges minerals from the mantle and is then vented from another fissure several metres away. The seabed temperature is around 2°C, but temperatures can reach 350°C beneath the seabed. The water, pushed out under high pressure, emerges as a geyser or a hydrothermal vent. The minerals slowly deposit around the vent as polymetallic sulphides. Over thousands of years, these regions have become rich in minerals.

For the last few decades, countries have been exploring seafloors and estimating the amount of deposits there. The need for energy security, and the quest for minerals for renewable energy batteries are spurring the search.

AWAITING RICH DISCOVERIES

The Indian Ocean floor is one of the least explored water bodies, and India is among the early players in the region. It already has exploration contracts in two other areas — the Central and South West Ridges of the Indian Ocean. "Last year, we discovered four active and two passive vents in that area," says John Kurian, Group Director, Deep Sea Exploration Group of the Goa-based National Centre for Polar and Ocean Research (NCPOR), the nodal body exploring for polymetallic sulphides. Germany, South Korea and China are other explorers in the Central Indian Ocean Ridge.

Passive vents are those that get blocked over time due to seismic activity, and the water then finds another fissure to vent through. They are usually found near an active vent. Passive vents are important for mineral prospecting, since active vents support unique chemosynthetic-based ecosystems and should ideally remain undisturbed.

"Finding a vent is not easy. The ocean is vast. A vent may vary in size from a few metres to some tens of metres. It is like looking for a needle in a lake," says M. Ravichandran, Secretary, Ministry of Earth Sciences (MoES).

To identify potential sites, researchers look for signatures in the water column using standard geophysical tests for temperature, turbidity, self-potential, and electromagnetic measurements. "A region around an active vent should have high dissolved iron and manganese in the water," Kurian says. Once the active vents are found, they search the bed for passive ones. This is done by collecting samples from research vessels or by deploying crewless remote underwater vehicles to take pictures and collect samples. The samples will be analysed for the richness of the deposits. "We have not reached that step yet," he adds.

With its human-rated submersible, Matsya-6000, India's National Institute of Ocean Technology (NIOT) is seeking to develop indigenous technology to observe the ocean floor through human eyes.

Alongside mineral exploration, a biological team has also been deployed to study and document the area's existing biodiversity. The ISA mandates that the exploring agency maintain records of the biological communities in the water column and on the seabed. Usha Parameswaran, who leads the biological team in the exploration group, underlines the need for documentation. "It is important to record the biology of a region, since it will provide the data for Environmental Impact Assessments of future projects," she says.

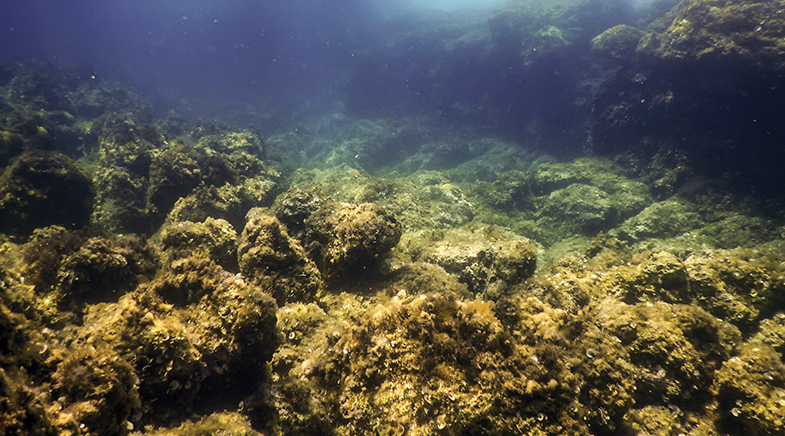

Parameswaran says the focus is on regions around passive vents, where the researchers will look for sessile (immovable) biota, which will be most impacted by mining. The process often involves sending a dredge with a net down to the bottom of the sea and waiting on the deck to see what it brings back. Sifting through the sand and rock, they are lucky if they find a bit of coral or a complete crustacean. The ocean floor along these ridges is uneven, and dredging it is a task.

To identify potential sites, researchers carry out tests for temperature, turbidity, self-potential, and electromagnetic measurements.

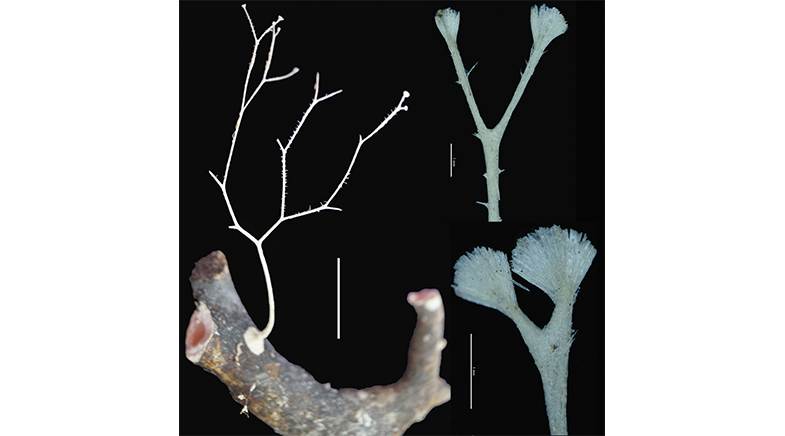

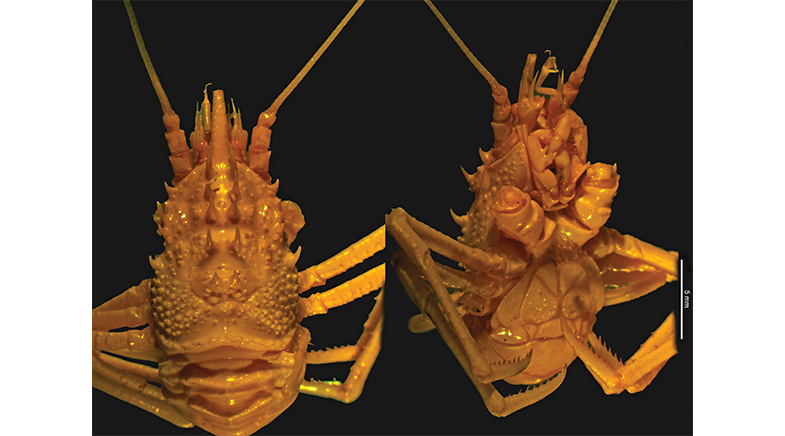

But once a new find is made, there is excitement all around. The researchers have named and described 10 new species from the Central Ridge region over the last few years. "These include four sponges, four corals and two species of squat lobsters," says Parameswaran. One of the new corals discovered is a bamboo coral, which was found growing on a dead coral. They also discovered several animal species, which had earlier been reported from distant waters, but had no records of being found in the Indian Ocean. These include a sponge reported only from the North Atlantic and a shrimp otherwise found in the North Pacific.

Exploration rights, however, do not give contractors the right to exploit the ridges for minerals. The ISA is yet to frame the laws for deep-sea mining. In fact, even the technology for it is mostly in the development stage globally. "We hope that by the time the law is ready, we will have explored and found mineral-rich sites, and will have a first-mover advantage in getting mining rights," notes Thamban Meloth, Director, NCPOR.

MINE TO MINE?

These are international waters, governed by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which established the ISA in 1994. The environmental pushback for deep-sea mining is strong. Commercial mining can destroy the ridges in numerous ways — ruin them geographically, destroy the biota of not just the seabed but the entire water column, and even trigger earthquakes, since the ridges form along plate boundaries. Add to it the noise pollution and anthropogenic light from machines in these dark depths.

Commercial mining can destroy the ridges in numerous ways. The environmental pushback for deep-sea mining is strong.

In fact, even countries with mineral deposits in their Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) have not yet begun mining commercially. Norway, which discovered rich offshore deposits of copper and rare-earth minerals such as selenium, had approved plans to allow mining in 2024 but suspended the decision amid domestic and international protests. Papua New Guinea, Fiji and Vanuatu declared a moratorium on deep-sea mining in 2019. Their waters are rich in gold deposits. Japan, meanwhile, has declared its intent to test mine for rare-earth-rich mud from the seabed off the Minamitori Island, a coral atoll, in 2026. The U.S., which is not a party to the ISA, recently announced its intention to accelerate the development of deep-sea mining resources.

Deep-sea minerals are found in two other forms: Polymetallic nodules (PMN) and cobalt crusts on seamounts. Both are formed in regions of the ocean where currents are not too strong and sedimentation is low. PMNs look like clods or potatoes. They are formed over a "seed" — a shark tooth, a bone shard or a rock. Mineral precipitation from the water accretes around these seeds, and over millions of years, they become PMNs, rich in nickel, cobalt and copper. The Clarion-Clipperton Zone in the Pacific Ocean between Mexico and Hawaii has abundant deposits of PMNs. Many countries and companies have exploration contracts there.

India has focused on the Indian Ocean, with a contract to explore the Central Indian Ocean, which, the MoES estimates, has PMN resources of 380 million metric tonnes (MMT) — including 4.7 MMT nickel, 4.29 MMT copper, 0.55 MMT cobalt and 92.59 MMT manganese (bit.ly/Moes-estimate).

The only country exploring PMN in the Indian Ocean, India is developing technology to mine the resources. The mining process includes picking up nodules from the seabed, crushing them in situ, and pumping the slurry first to an intermediate collection point in the water column and then to the support ship. An NIOT team, under Commander Gopakumar K., has developed the seabed miner Varaha-1, named after an avatar of Vishnu. Varaha-1 has already demonstrated the capability of crawling on the seabed at a depth of around 5,000 m. Trials for the remaining stages are underway. However, this will only be a technology demonstration, not a commercial mining system.

Cobalt crusts are metallic layers that form on the flanks of seamounts or underwater mountains and plateaus. The process of their formation is similar to the formation of PMNs, except that the crusts form on a substrate of rock and can be found in shallower waters, too. Manganese, nickel and other rare-earth minerals are also associated with cobalt crusts. "India had applied for a contract to explore the Afanasy Nikitin Seamount in the Central Indian Ocean, around 3,000 km from India's coast in 2024. However, since Sri Lanka has claimed these underwater mountains as part of its continental shelf, the contract hasn't been allotted to either party so far," says Meloth.

Meanwhile, the Geological Survey of India has identified regions within India's economic zone as prospective sites for cobalt crusts and PMNs. These are around the Andaman and Lakshadweep waters. It identified these sites based on preliminary explorations using images from remotely operated underwater vehicles and chemical analyses of water samples. A detailed exploration is yet to begin.

Mining cobalt crusts is challenging, with the machinery having to negotiate mountainous seabeds. Moreover, the thickness of the crust on the rock needs to be commercially viable. The scale of environmental destruction could far exceed the gains.

Mining PMNs seems most feasible, as borne out by the number of exploration contracts — 19 — with the ISA, many held by private entities with a keen commercial interest. However, mining threatens to damage the fragile underwater world. Deep-sea life is adapted for long timespans — greater longevity and slow growth. The first long-term Disturbance and Recolonization Experiment, established in the Peru Basin in 1989, to understand the ecological impact of PMN mining showed that the benthic biota had not fully recovered even seven years later, and by 2015 track marks from the experimental mining machine were still visible on the seabed (bit.ly/disturbance-impact). A recent study on test mining PMNs in the Pacific showed a one-third loss in biotic diversity and density on the ocean floor and damage on the water column where the bilge was pumped out (bit.ly/ocean-diversity).

As mining technologies develop, underwater realms will be under increasing threat. Circular economies that can recover minerals from end-of-life products may address demand to an extent. Game-changing technology may also come to the rescue of seafloors. With sodium in abundance in seawaters, experiments are already underway to develop sodium-based batteries to replace lithium ones. The sea may come to the rescue of the planet, but explorers may also need to watch out for troubled waters.

See also:

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH