Time to chip in

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 01 edition 03 :: Sep - Oct 2021

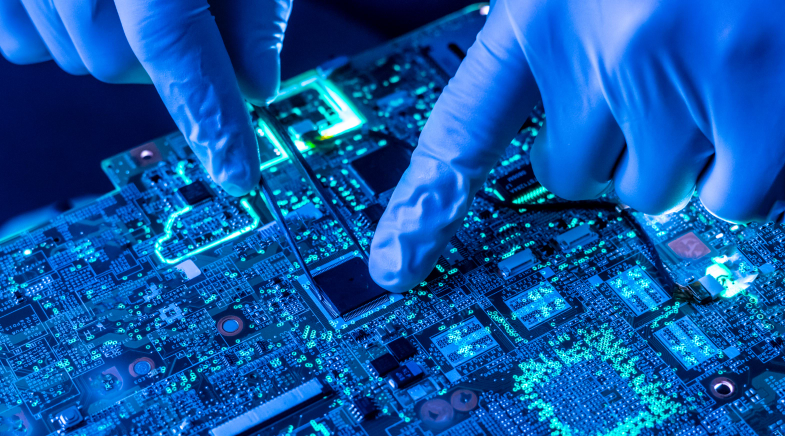

After decades of delays, the reality of the marketplace is likely shaping India's effort to establish a semiconductor manufacturing base.

For nearly three decades, every announcement in India of a stated intention - by the government or by private players - to invest in semiconductor fabs signalled the triumph of hope over bitter experience. That's because every such ‘big bang' announcement has typically tended to end with a whimper when the realities of infrastructural shortcomings, the absence of a deep-enough market for semiconductor chips, and just the overall cost inefficiencies that abound in the system hit home.

And yet, when Tata Sons Chairman N. Chandrasekaran announced, on August 10, that the Group was planning to invest in a fab, the overwhelming sentiment with which industry experts and observers greeted it was not of weary cynicism. To many, this time, it felt different.

What accounted for this turnaround in sentiments? For starters, this was the first time a major Indian company had got behind the project to establish a semiconductor manufacturing facility. Second, some of the other recent business forays by the Tata Group indicated that its fab enterprise was part of a larger ecosystem it was building for itself. Indicatively, the Group had recently ventured into 5G and into electronics manufacturing, and semiconductor chips are a vital component in both those businesses.

And unlike in the past, when ‘big bang' fab announcements by prospective players had not been followed up, the Tata Group moved with great alacrity. It had even identified a few potential locations to set up an Outsourced Semiconductor Assembly and Test (OSAT) facility, a third-party service offering of semiconductor assembly and testing of integrated circuits or chips. The final choice of location is expected to be announced soon; and the plant itself will likely be in place in a year.

Even before the August 10 announcement by Chandrasekaran, the Tatas had been lining up key players for the project. The Group has brought in P. Rajamanickam, who had in 2003 co-founded Tessolve, a semiconductor and solutions company, to head the new OSAT business. Rajamanickam, an IIT Kharagpur alumnus, is an industry veteran with nearly four decades' experience in semiconductors. "He single-handedly built Tessolve, India's first semiconductor testing company," says Muthukrishnan Chinnasamy, CEO, Semiconductor Fabless Accelerator Lab (SFAL), Bengaluru. The Tatas had also inducted Randhir Thakur, President of Intel Foundry Services, as a Director of Tata Electronics. Industry watchers see these two high-profile appointments as an indication that the Tata Group is backing up its stated intentions on the semiconductor manufacturing space with concrete action.

A COMPELLING NEED

For the Tatas, as for India, a foray into the semiconductor business is now considered a necessity. Early this year, the Group set up Tata Electronics as a subsidiary to manufacture electronics components. It signed an agreement with the Tamil Nadu government for manufacturing mobile components, with the factory to be built near Hosur, about 60 kilometres from Bengaluru. Last year, the Group had set up a medical and diagnostics division, which licensed the COVID-19 test Feluda from the Institute of Genomics and Integrative Biology in Delhi. The Group had also invested in Tejas Networks, a telecom equipment manufacturer in Bengaluru.

There have been several false starts on the road to establishing a semiconductor chip manufacturing facility in India.

All of these devices require semiconductor chips in volumes, and the manufacture of the devices will be affected by the current global shortage. The demand for electronics devices has been increasing steadily in India. According to the Directorate General of Commercial Intelligence and Statistics, India's electronics imports in 2020 were worth about $60 billion, and are expected to rise rapidly over the next decade. "It is imperative that policymakers consider electronics as a priority sector," says K. Krishna Moorthy, CEO and President, India Electronics and Semiconductor Association (IESA), who was previously with Rambus Chip Technologies and National Semiconductor.

HISTORY OF FALST STARTS

Industry insiders had foreseen this supply-constrained situation at least three decades ago, and had made repeated attempts to persuade successive Indian governments of the merits of setting up semiconductor manufacturing in India. For instance, in the early 1990s, expatriate Indian engineers led by Arya Bhattacherjee - the founder of Arcus Technology (later acquired by Cypress Semiconductor) - proposed a fab under the government-owned Indian Telephone Industries. It was called off - supposedly because of bureaucratic indecision.

There were several other false starts on the road to establishing a semiconductor chip manufacturing facility in India. In the mid-1990s, Texas Instruments had agreed to finance half the cost of setting up a fab if the government put in the other half, but that offer was not accepted. A few years later, the government sought partners in design and fabrication for what was known as the Semiconductor Complex Limited (SCL) in Chandigarh, which started operations in 1983. Motorola, STMicroelectronics and Matsushita had expressed interest, but they withdrew because of the government's delay in choosing a joint venture partner and the perceived lack of a domestic market. Later, a fire forced the Semiconductor Complex to be shut down.

In 2000, Teamasia Semiconductors proposed a fab and design centre in Hyderabad, but the plan never came to fruition. In 2004, the Indian government said it was willing to fund part of the costs to set up a fab, and held talks with Intel and other semiconductor firms. Again, nothing came of them. Around the same time, Intellect Inc., a South Korean company, had approached the Andhra Pradesh government with a plan to build a $1.6 billion fab, but the project failed to win approval. In 2005, a plan for a fab to make memory chips for mobile handsets and consumer electronics products was proposed in Kochi in Kerala by the locally based NeST Group along with an unidentified Japanese company.

The Andhra Pradesh government proposed a Fab City (to be located in Hyderabad) to attract chip firms to set up fabs, pitching to IBM and Applied Materials in 2005 without success. Intel, which had expressed interest in setting up a fab in the country, called off plans for an assembly and test facility - evidently because the Central government declined to grant it the concessions it had sought. Later, a $3 billion fab was proposed to be set up in Fab City by SemIndia in partnership with AMD, in which the government was ready to take 26% equity.

Over the years, there have been many other reports - and, in some cases, idle speculation - of efforts to establish a fab in India. STMicroelectronics was reported to be planning a fab near New Delhi, although the company denied this report. A proposal by the India Semiconductor Association (now the India Electronics and Semiconductor Association or IESA) to the government to set up a $1.5 billion fund to expressly encourage chip manufacturing in India by enabling it (ISA) to take equity was not approved.

In 2006, the foundation stone for a fab proposed by SemIndia was laid near Hyderabad, but the project never really advanced beyond that. That same year, IBM and Atmel were reportedly the main bidders for a new government initiative to upgrade the Semiconductor Complex, but that too fizzled out - in the same way that the proposal made a decade earlier had. All along, the framing of India's national semiconductor policy was repeatedly delayed, ostensibly on account of differences between the Finance and the Information Technology ministries. Understandably, these delays left stakeholders and potential investors frustrated in the extreme.

Industry experts reckon that with the right policies, India can become a critical link in the global supply chain, currently dominated by China.

In 2012, Accenture said it had been tasked by the government to review investment proposals from global technology providers and investors interested in building semiconductor fabs in India. In 2014, the government approved plans for two fabs, one by Jaiprakash Associates (together with Tower Semiconductor and IBM) and another by Hindustan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (HSMC) in partnership with STMicroelectronics and SilTerra.

Fund manager Next Orbit is working on a $3 billion fab in Gujarat: four years ago, it had said it was planning as many as three fabs in India. The failure of these plans has been attributed to a combination of factors: lack of serious intent on the part of promotors; the failure at the top levels of government and bureaucracy to act on investment proposals; the lack of a strong electronics production ecosystem in the country; high capital costs and long gestation periods; inadequate logistics; and the lack of a strong materials science and semiconductor research and development ecosystem in the country.

Over the past three decades, there have been some improvements in many of these areas.

One additional factor has compelled governments around the world to secure their semiconductor supply chains. The COVID-19-induced supply constraints, particularly originating in China, have provided an impetus to these efforts. In India's case, those problems have been compounded by a deterioration in relations with China following the outbreak of hostilities in the Himalayan border areas.

OPPORTUNITY FOR INDIA

The ongoing effort to redraw supply chains to reduce dependence on China will likely play out over a longer time-frame. Base-level materials are available in India, but they need to be upgraded to a sufficient level of purity if they are to be used in semiconductor manufacturing, says Moorthy. However, he reckons, when that is done, the extent of value addition will be significant, and India can export many of these items and become a critical link in the global supply chain, which is currently dominated by China.

India's semiconductor ecosystem is gradually evolving: it now comprises a few dozen fabless chip firms, nearly a hundred captive research and development centres of global chip firms, chip design services offered by Indian companies such as Wipro and HCL, and one or two fabless chip incubators. The Tata Group's OSAT business alone can be scaled up to $150 billion by 2025, according to IESA estimates.

The global semiconductor industry has several Indian-origin engineers in top levels of leadership. "There is a need to leverage the expertise of top executives of Indian origin in the upper echelons of global semiconductor firms and outline a strategy to develop the overall semiconductor ecosystem in India," says Satya Gupta, former Chairman of IESA. It appears that after decades of delays, the harsh reality of the marketplace may stir policymakers to act on this front.

Also read: A fab roadmap for India

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH