The 'Seagull' who soared to space

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 02 issue 01 :: Jan - Feb 2023

Sixty years ago, Valentina Tereshkova became an unlikely symbol of Soviet space ascendance.

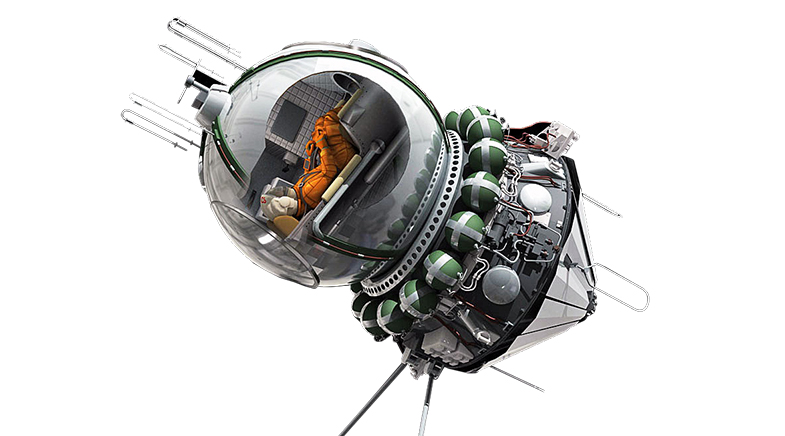

On June 16, 1963, the official TASS news agency of the erstwhile Soviet Union, otherwise given to over-the-top propaganda, put out a statement that was remarkably bland, despite the momentous nature of the announcement. It read: "At 12.30 pm Moscow Time, a spaceship, Vostok-6, was launched into orbit piloted, for the first time in history, by a woman, citizen of the Soviet Union, Communist Comrade Valentina Vladimirovna Tereshkova."

With that matter-of-fact news-break, the Soviet Union signalled to the United States – its Cold War adversary – and to the rest of the world that it had comprehensively won the 'space race' between the two superpowers, for the second time in two years. (In 1961, Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin had become the first human to go to outer space.) Tereshkova's accomplishment, at age 26, ended a scramble between the countries to be the first to send a woman to space. It was also an emphatic assertion of Soviet technological prowess.

Tereshkova's ascent to becoming the "First Lady of Space" – the title of her autobiography – was a classic Soviet story of proletariat struggle. Her father was a former tractor driver who enlisted in the Army during the Second World War and died in combat when 'Valya' (as she was known) was just two. Her mother, a mill worker, raised three children, and Tereshkova herself worked in factories before securing a technical university degree. Enthused by a friend, Tereshkova – who was good at sports (she could ski and had swum across the Volga River many times) – took up parachute jumping. When Gagarin made history, "I developed a disease called 'space'," she noted in her autobiography. "I decided I'll be a cosmonaut." She nervously applied, unsure she would qualify because of the "outrageous competition". In December 1961, she received a call to start training for a spaceship flight.

Her voyage signalled to the United States that the Soviet Union had won the 'space race' between them.

After months of intensive training, during which the speculative buzz in both the U.S. and the Soviet Union grew progressively louder, the launch date was set for June 16, 1963. Barely two days earlier, the Vostok-5 spacecraft had taken off with cosmonaut Valery Bykovsky aboard. An additional frisson of excitement was provided by the possibility that the two cosmonauts would have a "space rendezvous".

On the day of the flight, with words of encouragement from Gagarin, Chaika (Tereshkova's radio call sign, meaning 'Seagull') set off. Once in orbit, she excitedly radioed back to base: "I am Chaika. I see the horizon... How beautiful the Earth is! Everything is going well."

1963

BRUSH WITH DEATH

There were two mission mistakes on Valentina Tereshkova's 1963 space voyage. The cosmonaut revealed in 2016 that after take-off, she discovered that the spacecraft was programmed to ascend, but not descend. Base station personnel fixed it after she alerted them. If they hadn't, she might have been lost in space. Somewhat less seriously, the mission staff had failed to pack her toothbrush, forcing her to brush in the old-fashioned way. "I had toothpaste, and water, and my hands," she said.

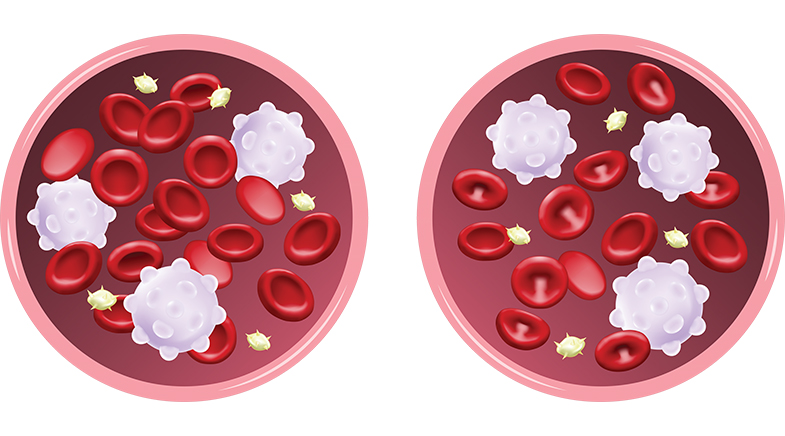

The Vostok-6 mission was tasked with studying the effects of spaceflights on humans, and specifically, on a woman. There are varying accounts of Tereshkova's experience on board. Official accounts claimed that she carried out visual observations, experiments, and communication sessions with Earth, including a "Kremlin to cosmos" conversation with Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev. However, in his book Soviets in Space, military historian Colin Burgess noted that Tereshkova "suffered from headaches and vomiting" and that her sleep patterns were irregular. Citing accounts of extracts from the diaries of Soviet General Nikolai Kamanin, who headed the cosmonaut training programme, Burgess further claimed that Tereshkova "did not perform at all well" and that an "infuriated" Kamanin "wrote a scathing assessment of her performance..." Even the "space rendezvous" was a damp squib: although the two cosmonauts were in radio contact, neither craft reported seeing the other.

1963

STAMP OF HONOUR

After Tereshkova's return to Earth, she was celebrated as a hero. Postage stamps were issued in her honour. The trademark Soviet-era nesting matryoshka dolls came up with a female cosmonaut series. A lunar crater, on the far side of the moon, was named after her. In 1967, an asteroid was named 1671 Chaika, after her radio call sign. Several pop songs, even in the West, paid homage to her epic voyage. But in Ukraine, streets that bore her name have been rechristened following the 2022 outbreak of war with Russia.

WIKICOMMONS

When Tereshkova returned from her mission, she was feted as a hero – and became a global goodwill ambassador and a propaganda vehicle for Communism. At a rally in the Red Square to felicitate her, Khrushchev noted that she had completed 48 orbits of the Earth. "Her flight lasted longer than all the American astronauts together have spent in space... She has demonstrated once again that women raised under socialism walk alongside men in all the people's concerns..." he gloated.

The hyperbole was perhaps pardonable. After all, the 'Seagull' had soared to space and written her name in the stars.

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH