As solid as a rock

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 03 issue 10 :: Nov 2024

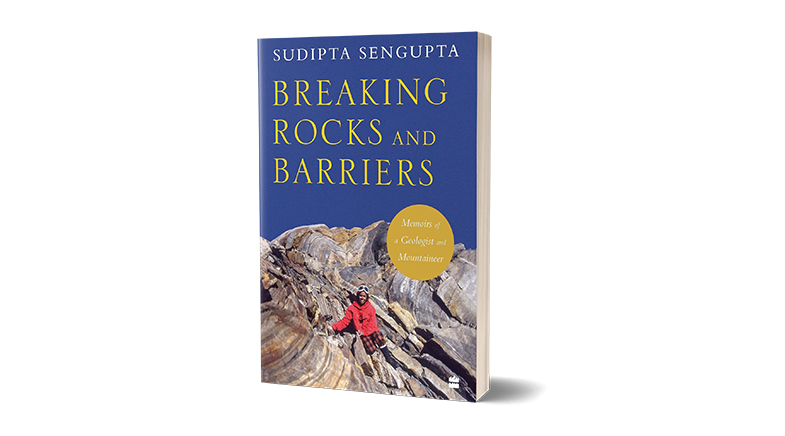

Geologist Sudipta Sengupta coaxes the secrets of the Earth by talking to rocks and tapping their memories.

Two ideas seem to have shaped Sudipta Sengupta's memoir. The first was at age 16, when she was interviewed for admission into Jadavpur University. She had come to the interview thinking she would follow in her father's footsteps and study physics. But someone on the interview panel asked: "What do you like to do most in your free time?"

"Travel," she said.

"Then you should study geology!" said someone on the panel — and she did. That's how one of India's best-known geologists chose her path in life: by confessing to a fondness for travel.

The second was a quote from the geologist Hans Cloos: "We need to have a dialogue with the Earth. Silent rocks remember everything."

This spirit runs like a sleek thread through the book. You can believe Sengupta keeps up that dialogue, talks to rocks, so much so that they are almost her friends. She tosses out names of rocks, or other geological terms, as if they are indeed familiar friends who need no introduction: "quartzite with some conglomerates" and "quartzose mica schists", "enderbitic gneiss" and "khondalite". They are her companions throughout her geological and other travels in India, Scandinavia, Spain, the U.K. and Antarctica. Famously, she was one of the first Indian women to set foot on that ice-bound continent, intent as always on listening to what the rocks there had to say.

Then there are observations such as: "The Indian plate is still moving towards the Tibetan plate at a rate of a few centimetres per year." It's a geologist's alarm call. Because in a relatively short slice of geological time, what those plates are doing, a few centimetres each year, will manifest itself far more expansively, possibly even disastrously. Yes, that's geological time. Among geologists, "time has an entirely different meaning and is measured in millions of years".

So it's from these rocks, from their "silent" memory of all those millions of years, that Sengupta coaxes all manner of secrets about the planet.

TRIUMPH AND TRAGEDY

She is also a mountaineer, as passionate about climbing as she is about geology. Much of the first half of the book is about mountains, and we get a vivid sense of the hardships climbers must face. Steep slopes, winds to make you stagger, slippery ground, the cold. Sometimes, leeches.

Her encounter with leeches brought back a long-ago memory from a trek in Madagascar, when my guide glanced at the leech that had drenched my sock in blood. "C'est rien!" he said, waving his hand. "It's nothing!" Similarly, in spelling out her discovery, one evening after a long trek, of leeches grown fat on her blood, Sengupta airily tells us they are essentially harmless creatures.

But with the hardships, of course, there's also exhilaration. Arrive at the goal for the day, climb a particularly difficult stretch, overcome doubts and exhaustion, reach a summit... Even years later, Sengupta savours each such triumph. There is also great tragedy. She's part of a women's team that summits an unclimbed peak in 1970, overcoming treacherous terrain and weather conditions. On the way down, the two women who reached the peak with her die, and one of their bodies is never found. Sengupta is devastated. Even as she mourns, you sense that she understands all too well that such are the dangers in this passion she pursues so diligently.

There's tragedy in her geological travels, too. On her second trip to Antarctica in 1989, four colleagues die of carbon monoxide poisoning in their tent. For two days, she and two colleagues can't stop "talking about the deceased". Eventually, still aching from the loss, Sengupta resumes her conversations with her rocks. It was "the only way to divert my mind", she writes. And she is soon "rewarded": she finds "mafic and ultramafic rocks" that suggest "minerals formed at a great depth under the Earth's crust".

I really don't need to know what "mafic and ultramafic rocks" are. For I understand what they mean to Sudipta Sengupta, and that they will help her push the frontiers of geology ever outwards. For, indeed, that's the glowing spirit of this fascinating memoir.

Once a computer scientist, Dilip D'Souza now writes on mathematics, among other things.

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH