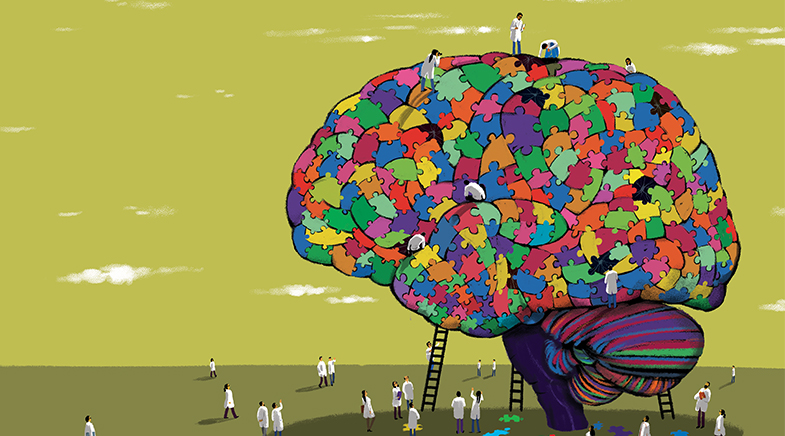

Getting to know the brain

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 04 issue 01 :: Feb 2025

Researchers around the world are collaborating in an effort to understand the human brain in unprecedented detail.

For at least a decade, even as he treated patients who were destined to die, George M. Varghese had been longing to look at rabies-infected brains in high resolution. He works at the Christian Medical College (CMC) Vellore, where he is the Head of the Department of Infectious Diseases. Despite the availability of a vaccine, more than 50,000 people die of rabies infection every year, as no treatment works after the symptoms manifest themselves. Rabies is an unusual disease. The virus does not cause direct cell death but travels through the nerves to the brain and hijacks its autonomic control, resulting in respiratory failure and cardiac arrest. Does it leave an imprint on the brain about the mechanism of this hijacking? Varghese had the brains but not the technology to look inside them.

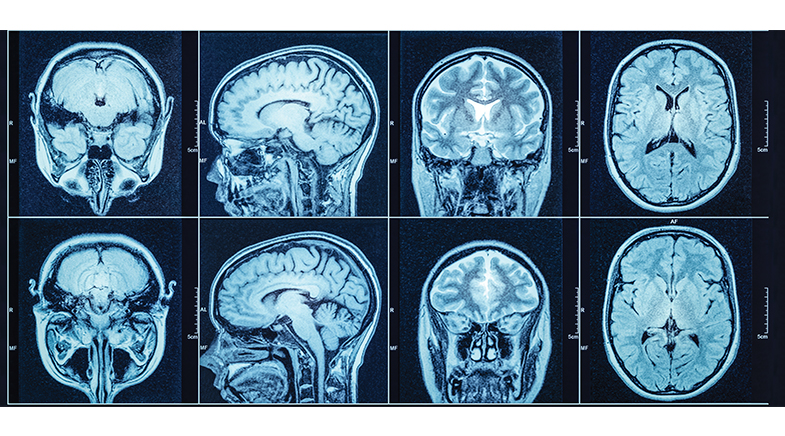

It is not easy to see inside a brain, either living or dead. Light does not penetrate the brain tissue more than a millimetre. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) has a resolution of 1-2 millimetres, which is too low to see the deep structure of the brain. Imaging the neurons require resolutions of a few microns, or a few millionths of a metre. Seeing their connections require resolutions of nanometres, or a few billionths of a metre. Deconstructing the brain and then reconstructing the images require imagination, expensive equipment, technological skills, and exquisite project management. Nobody had made a three-dimensional image of a whole human brain at the cellular level. Sometime around 2018, Mohanasankar Sivaprakasam broached the idea of creating precisely that.

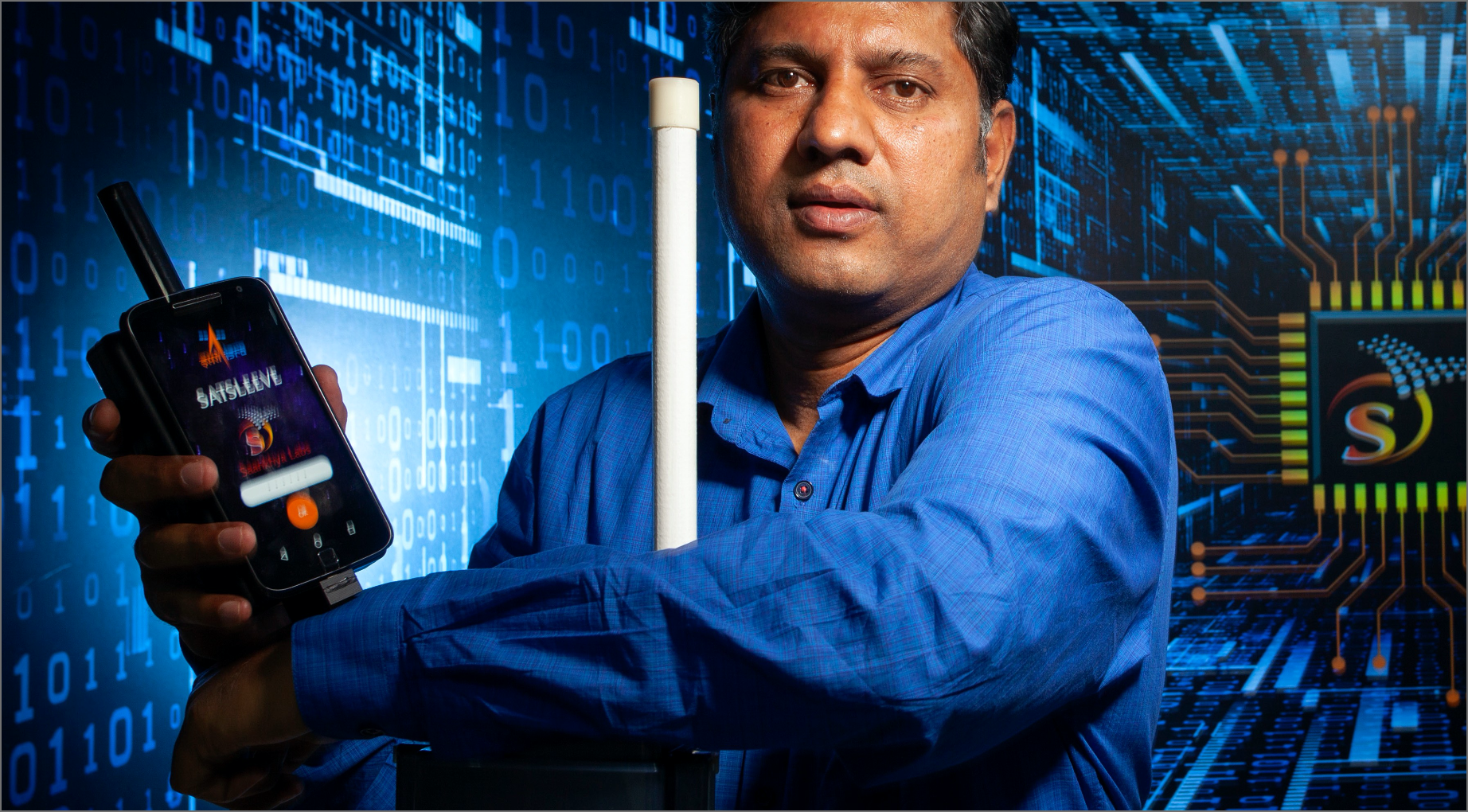

A Professor of Electrical Engineering at IIT Madras, Mohanasankar had also managed the Healthcare Technology Innovation Centre at the institute. Varghese and Mohanasankar had been good friends for a decade, after a chance meeting at a conference in Chennai. However, IIT Madras had no history of neuroscience research until 2014, when Infosys co-founder Kris Gopalakrishnan established three Chairs in computational neuroscience. During a conversation with Partha Mitra, a Professor at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York and a recipient of the Chair, Gopalakrishnan had asked: "Can we do something that can put IIT Madras on the global map?" A plan to image whole brains was the result.

In December 2024, the IIT Madras team published the first data set: a three-dimensional map of a second-trimester foetal brain.

Studying the human brain deeply was the zeitgeist at that time in neuroscience. The Blue Brain Project in Switzerland was trying to digitally construct a mouse brain. The European Union had started the €1 billion Human Brain Project in 2013, to study the brain in time and space, by working out its structure and watching how it evolves. The Allen Institute in Seattle was making a detailed atlas of the mouse brain. A large project to map the fly brain in exquisite detail had begun in several institutions, especially at the Janelia Research Campus in Virginia in the U.S. Smaller projects around the world were trying to image portions of the human brain. All of those were established institutions in neuroscience. IIT Madras had to put together everything from scratch: the money, the lab, the equipment, the brains.

Through a decade or more, depending on the pace of development, IIT Madras was hoping to slice and image over 100 brains. Such a slice, 20 microns wide, would have several millions of neurons in it. CMC Vellore and the National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences (NIMHANS) in Bengaluru were to supply the brains post-mortem to IIT Madras. In 2018, Mohanasankar and his colleagues wrote up a proposal and sent it to the Principal Scientific Adviser (PSA) to the Prime Minister, K. VijayRaghavan, who sent it to several scientists for comments.

The replies were not encouraging. "People responded to the proposal saying that it was too ambitious and that I shouldn't fund it," says VijayRaghavan. "So, we decided to fund it." The large ambition was precisely what attracted VijayRaghavan. The funding of ₹31 crore from the PSA office was for a proof of concept, but it gave Gopalakrishnan the confidence to fund it on a larger scale. "I said that I would support the people for ten years," says Gopalakrishnan. "No questions asked." Funding for equipment had to be obtained from other donors. The new centre was called the Sudha Gopalakrishnan Brain Centre (SGBC). Mohanasankar was to head it.

As happens in India occasionally, IIT Madras had jumped directly to the human brain, leapfrogging over all other animals. The project has its critics, and not merely because it is too ambitious. Some neuroscientists don't believe that imaging dead human brains is very useful. The working brain, after all, is an interplay between electrical signals and transient chemicals. They feel that mapping the circuits and chemicals in real time is important to understand the functioning brain. For some others, the imaging resolution of the slides is too low. Micrometer resolutions are not good enough to see the synapses, the junctions between neurons, which are critical parts of a brain network. The IIT Madras researchers, however, were confident of unearthing valuable information at the mesoscopic scale, in between resolutions of nanometers and millimeters.

DHARANI is the largest publicly accessible digital dataset of the human foetal brain: it features 5,132 plates of developing human brains.

In December 2024, the team published the first data set from the project in the Journal of Comparative Neurology. It was a three-dimensional map of a second-trimester foetal brain. It was also the second brain map to be published in the journal, the first being a gene expression map – from the Allen Institute – of 21,000 mouse genes, for which the journal had devoted a 350-page special issue in 2016. The IIT Madras foetal brain map was called DHARANI (A 'meta-atlas' is mapped). It was the first map of a full foetal brain at this cellular resolution. In less than a year, the map of a third-trimester foetus will be ready to be published. The centre is working on adult brains as well, including a rabies brain. It has already acquired 200 brains, a difficult task to achieve in any country, especially developed countries.

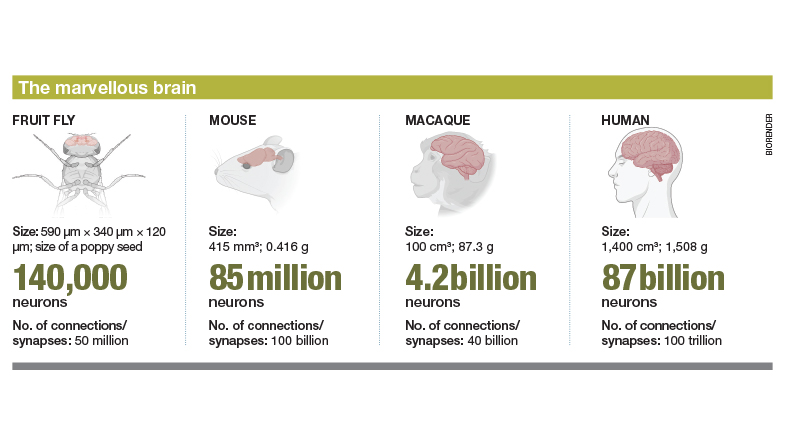

A high-resolution map of the human brain can have many uses. They can become reference maps for radiologists. A set of maps from the foetus to the adult brain can help biologists understand brain development mechanisms. In specific cases like rabies, they can provide clues about how the virus interferes with the neural processes. However, for many neuroscientists, the holy grail of the field is a connectome of the human brain, a complete map of all the connections that exist between neurons. No one really knows the true extent of a human connectome. To be precise, biologists don't know the number of neurons in the human brain, although informed guesses put it at roughly 86 billion and the connections at 100 trillion. It is too big for contemporary technology to explore. Neuroscientists had to start with a small brain.

THE FLY IS COMPLEX, TOO

The world's first connectome project had got under way in the 1960s, when Sydney Brenner – then at Cambridge University – decided to work on the brain of the roundworm Caenorhabditis elegans. Through laborious manual work, his team mapped out by hand all the connections between the 302 neurons in the worm's brain and published the work in 1986. This technique had severe limitations. However, the availability of computers and improvements in computer vision algorithms in the 21st century made it possible for scientists to tackle larger brains. Their first serious target was the fruit fly.

After the Janelia Research Campus was set up in 2006, several teams there started work on the fruit fly connectome. This institution is part of the non-profit Howard Hughes Medical Institute and has nurtured large groups of neuroscience researchers. A fruit fly brain is small compared to the human brain: just 140,000 neurons. However, the fly still leads a rich life. It can stop and turn in mid-flight, respond to odours, exhibit spatial awareness, perform social interactions. The male flies sing. If its brain were any smaller, the fly may not have shown such complex behaviour. If the brain were larger, mapping its circuits would be beyond the ability of the technology of the 2010s. The fruit fly brain was in a sweet spot.

SGBC researchers developed a method to harvest brains from inside contained chambers and cooled them to–80°C for storage.

In a project that began in 2014, Janelia researchers chopped the fly brain using diamond knives into slices a few nanometers thick, roughly one-thousandth of the thickness of the human brain slices at IIT Madras, and imaged them using transmission electron microscopes. Techniques to do the slicing were improved over a period of time at Janelia. The microscopes were also built there. The images were put together into a three-dimensional map, and Google engineers helped locate the neurons and the connections through artificial intelligence. It was not a complete map; there were neurons that still needed to be proofread. Over a period of five years, after the data were made public, a consortium of researchers around the world led by Princeton University finished the proofreading and developed the full set of connections in a female fly brain. It was published in Nature in October 2024 (go.nature.com/40seFsc).

The proofreading itself produced at least 50 research papers before the full connectome was published, showing the power of open science. "I would say that it has been transformational," says Mala Murthy, Director of the Princeton Neuroscience Institute and co-leader of the FlyWire consortium which finished the proofreading. "There is no recent study that of the Drosophila brain that does not leverage the connectome." The connectome has provided insights into how the fly perceives odour, how it stops in mid-flight, how it turns, how it navigates, how it sings, and so on. The Nature edition in which the connectome was published had nine other papers on different aspects of fly behaviour. "If we can solve it in the fly," says Murthy, "we can solve it in other systems."

The SGBC team sliced the brain, used sticky tapes to which the brain tissue adhered, and transferred it to a slide.

For example, at Janelia, Vivek Jayaraman leads a group researching an area called mechanistic cognitive neuroscience. To use a human analogy, this group tries to map all the circuits in the brain that make understanding possible. Jayaraman's favourite example of this cognition is the way we can shut our eyes and point to the room door, almost always correctly, even if we are in a completely new building. This is because human beings have a spatial map in their brains. How does the brain create this map, in terms of the cells and synapses interacting in specific ways? "You can ask this question all the way down to the level an engineer likes," says Jayaraman. "These are the component parts, this is how they wire up, this particular pattern of wiring produces a circuit of this nature. And, oh look, this is the computational property the circuit has." With the connectome now established, Jayaraman can see this happening in real time in the fruit fly.

Janelia scientists are pressing ahead with their connectome work, using a different method. Instead of cutting with diamond knives, they bombard the brain with gallium atoms and peel away thin layers of the tissue, which are then imaged using a scanning tunnelling microscope. Another full connectome, this time of a male fruit fly, will probably arrive by the end of the year. Elsewhere, neuroscientists are moving on to the mouse and the human brain. Technology needs to be improved for such studies. The mouse brain, for example, is bigger than the fly brain and so the image needs a larger field of view. The datasets will be larger, and so scientists need greater storage and processing power. The scaling is exponential. The fruit fly brain connections line up to 150 metres. The mouse brain circuits, when lined up, may reach a distance of 5,000 kilometres. The human brain network has a length of 5 million kilometres, scientists estimate. That's six times the distance to the Moon and back, all packed inside the skull.

The global capacity for storage is far short of what is needed for a human connectome. However, the foundational methodologies to develop a connectome have been established now for the fruit fly. Electron microscopy can image the brain at the level of the synapse, but scientists are developing other methods as well. One new method, called expansion microscopy, expands the brain tissue 20 times or more, thereby making it easier to see its structure. Developed in the lab of Ed Boyden of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), this technique uses polymers that swell inside the tissue and thereby cause a physical expansion. "It is not clear yet which method will be more successful," says Murthy. "But I think we will see a mouse brain connectome in the next ten years. I am optimistic about that."

THE MIDDLE PATH

Partha Mitra's research method was to slice the mouse brain thinly and examine it under a light microscope. He was a strong proponent of working on the mesoscopic scale, between the levels of individual variations and species-level structures, where he thought there was valuable information to be gleaned. It was natural for IIT Madras to extend this concept to human brains, but the complexities were much bigger. To go from a 0.5 cubic-centimetre mouse brain to a 1,300 cubic-centimetre adult brain was ambitious. The institution didn't need expensive electron microscopes, but would need to develop new methods or modify existing ones for the larger human brains. "There are over 120 parameters that need to be arrived at at the right levels for the imaging pipeline to work smoothly at scale," says Mohanasankar.

The holy grail for neuroscientists is a connectome of the human brain, a map of all the connections between neurons.

The funding from the PSA office for the project was approved in February 2020. Within a few weeks, the IIT Madras campus was shut down due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The SGBC continued to work through the next two years, forming a team and developing the infrastructure. Jaikishan Jayakumar from the Center for Computational Brain Research – its only scientist at that time apart from the IIT Madras faculty – moved to the SGBC, which got its lab by converting a car park of a new building on campus. Richa Verma moved from Deakins University in Australia – with a brief stint in between as a consultant – to the centre as Chief Scientific Officer. Both Jayakumar and Verma are neuroscientists, with a special interest in vision. They are also married to each other.

A team of engineers and technicians formed under their supervision and started to develop equipment. Their plan at that time was to slice and scan only adult brains. However, J. Kumutha, Dean of the Saveetha Medical College and Hospitals in Chennai, told Mohanasankar that it was easier to secure foetal brains for research. It also made sense for the centre to look at both the developing brain and the adult brain. IIT Madras had a good source for foetal brains: Suresh Seshadri, Director of the Fetal Intervention Centre at MediScan Systems, was a Professor of Practice at the institution, and readily agreed to supply brains from the centre. The foetal brain, however, was more difficult to slice. In any case, the project team had to develop a procedure to handle the brains from the clinic to the lab and through several stages till it was sliced and scanned.

As more brains are scanned, the IIT Madras platform gives a foundation to ask more questions – such as how anti-depressants work.

To avoid spread of infection during COVID, Varghese and engineers at the SGBC developed a method to harvest brains from inside contained chambers. After harvest, the brain had to be cooled to –80°C for storage. The brain is roughly 75% water; when cooled, it cracks, due to the expansion of ice. So, it needed to be put in saturated sucrose solution for four to six weeks, based on the size of the brain, till sucrose replaced enough of the water. It was an old method that needed to be optimised for large samples. Similarly, the project team had to perfect a method of slicing the brain at widths of 20 microns. This was done using sticky tapes to which the brain tissue adhered, and then transferring it to a slide by dissolution of the adhesive. Then the slide had to be covered without wrinkles or air bubbles. A small slip in any of these steps would have affected the quality of data.

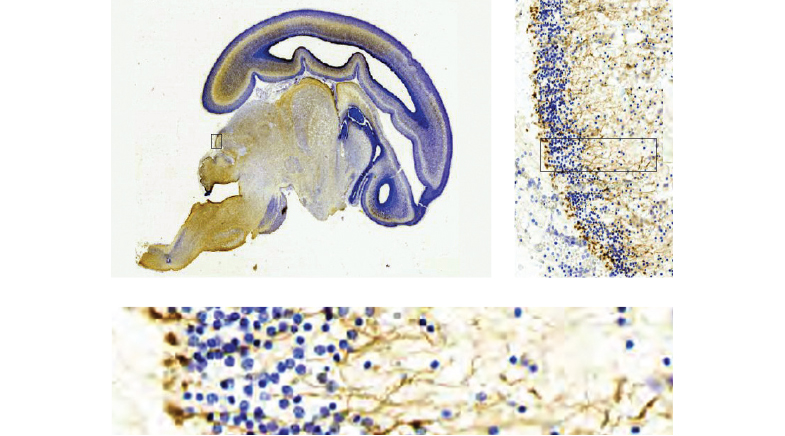

The tissue slices are stained in three different ways to show different parts of the brain: the nucleus inside the cell, the matrix outside the cells, and the myelin sheath of the neurons for connectivity and some histochemistry. Scientists at SGBC had to optimise the microscopes for the slide thickness and colour. Software needed to be developed for reconstructing and analysing a three-dimensional structure from the digital images. Over four years, the centre hired 150 people to continuously work on all these. It has also secured substantial additional funding from a variety of sources, including Premji Invest, Fortis Hospitals, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and Prem Watsa.

A PLATFORM WITH POTENTIAL

Vidita Vaidya, Professor in the Department of Biological Sciences at the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR), Mumbai, was on the review panel for the project and had a ringside view of its growth from its initial days. "It sounded like a crazily ambitious idea but so exciting," she says. Plenty of neuroscientists around the world had imaged the brain, but only in areas of their interest. The Neuropathology Consortium at the Stanley Medical Research Institute in Maryland, for example, had sections of 60 samples of certain brain parts of people affected by mental disorders. Vaidya, who works on the neural circuitry of emotions and their changes in psychiatric disorders, thought that whole brain images looked more promising. So promising that she resigned from the panel to become a collaborator in the project.

The brain creates meaning out of what it sees and hears. This meaning is heavily influenced by the brain's emotional lens, by its ability to see value. "We respond more to things that matter to us," says Vaidya. "And for things to matter to us, our emotional circuitry has to be engaged." Vaidya studies such circuitry in mouse and rat models. Scientists can put electrodes into a rodent brain, genetically modulate its circuits, perturb the function of neurons in a specific part of the brain. So they can get a circuit-level understanding of specific things that happen in the rodent brain. However, they do not know whether such mechanism is transferred to the human brain.

For example, Vaidya wanted to know how psychedelics reduced anxiety. Her group gave psychedelics to a rodent and reproduced an anxiety-like behaviour in them (Psychedelic pacifiers). By delivering the drug to specific parts of the brain, an experiment that is possible on a rodent, they discovered that the drug action involved the ventral hippocampus. Through more experiments, they also identified the specific neurons in the hippocampus that are involved in the action of the drug. Then they reproduced the behaviour by perturbing those neurons in other ways, without giving the drug. The loop was now complete. None of this is possible in a monkey, let alone humans.

As more brains are scanned, the IIT Madras platform gives a foundation for Vaidya to ask similar questions. How do antidepressants like selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) work? They do not work identically in everybody. There are 14 kinds of serotonin receptors in the brain, and the drug's action is governed by the specific combination of serotonin receptors in specific neurons. Once scientists have a cellular map at a high resolution, they can look for chemical signatures in specific neurons at specific ages of the brain. "I think the platform is now laid to ask those interesting questions," says Vaidya. "If the right people come together, the right magic happens, and (it) will allow interesting scientific questions to be asked in the context of the human brain."

See also:

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH