The life digital

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 05 issue 01 :: Jan 2026

As the world gears up to embrace a sustainable future, scientists are mimicking biological systems to find solutions to disparate problems.

On a plain white wall, a sandy-coloured lizard nimbly climbs up against gravity. Atul Thakur observes it closely as the lizard trots up, synchronising its limb movements while pushing thousands of tiny strands of hair on its toes against the wall for a better grip. To balance every sharp move or turn, it swings its tail, which acts as a mini counterweight, stabilising its movement. The mechanism of the lizard's moves intrigues Thakur, a robotics researcher and Associate Professor at the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Patna. Lizards used to repel Thakur, but now he is fascinated by their ability to scale walls while handling weights beyond what their palms are meant to hold.

Thakur's interest in lizards was sparked in 2015, when he was awarded a research project by India's Department of Science and Technology to develop a 'spy lizard'. It was perceived that, unlike drones, which would be seen as adversaries by the enemy, a spy lizard, programmed to provide vital information to security forces, would appear innocuous and thus evade suspicion. At another level, such robots could also be employed for cleaning and repairing walls.

For Thakur's team, mimicking a lizard's wall-climbing ability was a challenge. The researchers first worked on the shape of a lizard, creating a structure with two front and two rear legs, connected to the spine via actuators, devices that convert energy into precise motion.

These actuators were programmed to synchronise the swinging of one front leg with its diagonal rear leg so that the robot moved like a lizard. They made the lizard stick to the wall using adhesive pads controlled by the actuators. The team continues to refine their lizard robot, creating better versions each time. Their current version weighs 100 grams, can carry a 20-gram payload such as a spy camera, and can climb for 15-20 minutes. As it is hard to communicate every bit of data to users, Thakur and colleagues have an artificial intelligence (AI) model that analyses camera footage and sends useful information to them (bit.ly/spy-lizard).

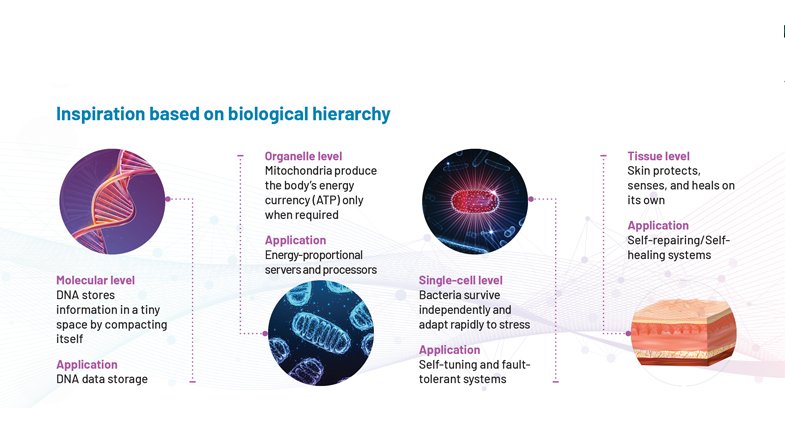

For the past few decades, scientists have been experimenting with lifelike hardware or replicating biological principles in software. Biological systems are optimised by evolutionary forces to become efficient, robust, and adaptable, while consuming low energy. Birds have evolved lightweight bones for energy-efficient flight. DNA repair mechanisms constantly fix errors, preventing mutations that could hamper survival. Bacteria adapt to antibiotics to live. The brain uses much less power than a computer to perform a task. Such efficiencies can help in daily activities if engineers successfully replicate the principles of life in industrial products.

Large language models with enormous capabilities but high carbon footprints have sparked greater interest in capable and energy-efficient biological systems.

As digital technologies penetrated disparate industries, engineers worried about their potential for failure. Algorithms and hardware worked well in the past decade, but are now overwhelmed by the enormous amount of data produced by digital devices. Engineers find it hard to get devices to handle this level of complexity efficiently with the limited resources at their disposal. In the past few years, large language models with enormous capabilities but high carbon footprints have sparked greater interest in biological systems that are both capable and energy-efficient.

To meet this challenge, scientists are now developing digital systems rooted in biological design, and technological advancements are helping make this shift possible. Smart materials, such as shape-memory alloys, graphene skins that can sense, and adhesive and self-healing materials, are helping hardware engineers transform rigid machines into lifelike, flexible, and responsive systems. Miniaturisation, additive manufacturing, and laser technology have enabled rapid development of hardware prototypes.

Scientists at the Indian Institute of Science (IISc), for example, have developed snake robots that can navigate rubble, pipes and tight spaces. IIT Madras researchers have designed soft magnetic robots that mimic the movement of an inchworm, and a group at IIT Indore has developed a jellyfish-inspired robot for noiseless monitoring of marine life. Similar efforts are being undertaken worldwide. Barbara Mazzolai's group at the Genoa-based Italian Institute of Technology has a robot that moves towards gravity and light, like climbing plants, and can be used for environmental monitoring. Fieldwork Robotics, based in Cambridge, U.K., has developed a raspberry-picking robot, taking inspiration from how the human arm gently harvests crops. Figure AI, based in San Jose, California, has created a robot that folds laundry and a warehouse robot. Demand for such lifelike robots is especially high in the industrial sector.

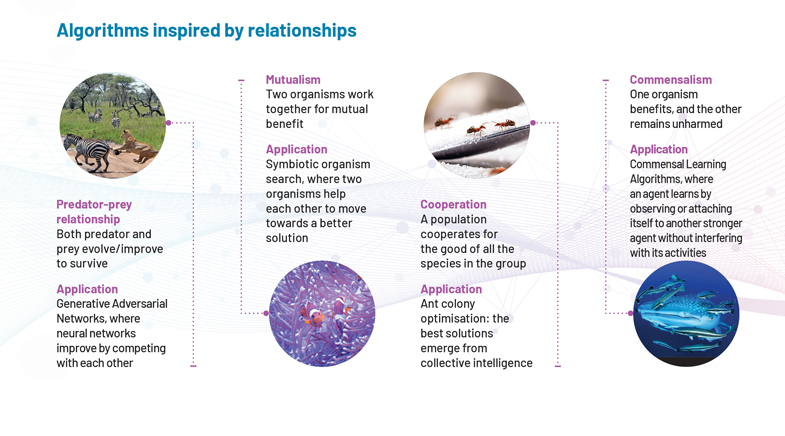

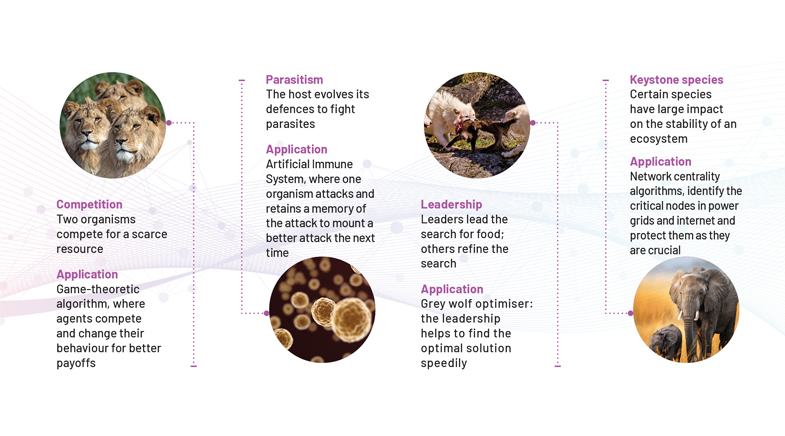

While bioinspired hardware is a recent trend, bioinspired algorithms developed in the last century — but failed to take off, as they were slow. These algorithms are now popular because of the need to solve complex and data-heavy problems, or even in situations where data may not be available. The availability of high computing power has enabled the testing, refinement, and use of bio-inspired algorithms that were otherwise difficult to run on the low-compute devices of the 20th century.

Miniaturisation, additive manufacturing, laser technology, and smart materials have enabled the rapid development of hardware prototypes.

Biology now inspires many modern digital technologies. Computer scientists are designing chips that learn and adapt on their own, and sensor engineers are mimicking how sense organs perceive the environment. The Internet of Things (IoT) is being developed to mimic how animal colonies communicate, using as little power as possible. Blockchain engineers take a cue from the immune system's ability to defend itself.

The relationship, however, is not one-way. Technology and biology share a symbiotic relationship, each propelling the other. New techniques and technologies, such as optogenetics, whole-genome sequencing, super-resolution microscopy, and cryo-electron microscopy, have enabled biologists to better observe, measure, and decode the inner workings of living systems and the behaviour of organisms and their groups. This, in turn, helps scientists to make better technology by mimicking biological systems. For example, high-speed cameras have enabled engineers to observe how insects and birds flap their wings, and this understanding has helped improve unmanned and crewed aerial vehicles. Similarly, high computing power and AI have been helping with genome projects and brain-mapping programmes, which, in turn, are pushing the field of brain-inspired computing.

As the world gears up to embrace a sustainable future, these biological systems, which are highly efficient, adaptable, intelligent, intuitive, and operate with low power, have become a guiding light.

COLLECTIVE INTELLIGENCE

Jagdish Chand Bansal, Associate Professor at the New Delhi-based South Asian University, is interested in the language that a population uses to communicate to complete a large task. During his PhD in mathematics at IIT Roorkee, he learned about swarm algorithms inspired by how animals in a swarm communicate to solve complex tasks. For example, ant colonies collectively find the shortest path to food using pheromone trails; bee swarms perform a waggle dance to decide on the best new hive location; and bird flocks coordinate their movement using simple local rules. He realised then that algorithms based on such communication and collective intelligence could be the backbone of IoT systems, robot fleets, autonomous vehicles, and sensor networks. Such systems could only succeed if their parts communicated efficiently, responded rapidly to environmental changes, and made tough decisions.

By 2014, when he delved deeper into the topic, there were algorithms inspired by swarm behaviour — such as Ant Colony Optimisation, Particle Swarm Optimisation, Artificial Bee Colony, and the Firefly Algorithm. While these algorithms were suitable for specific cases, Bansal realised that they had one flaw: all individuals copy the behaviour of a single individual, and therefore may settle for a mediocre result rather than seek a better option. Bansal found a solution to this in the foraging behaviour of the spider monkey population. Spider monkeys split into small groups to search for food, then later merge to share the findings. Each small group has a local leader, while the whole population has a global leader to follow. Inspired by this, Bansal developed an algorithm in which a population of agents splits into small groups to explore the entire search space for a solution, then combines later to decide on the best solution. "If they had been in a single group," says Bansal, "they would have explored a little area. But now, since they are in smaller groups, they have explored the entire search space in a larger area."

Bansal has been improving the performance of this algorithm and expanding its use cases. He has developed an enhanced version of the algorithm that explores the search space aggressively at the beginning and fine-tunes optimal solutions. His group has used this algorithm to detect plant diseases. A plant leaf has several features unrelated to disease, yet the usual algorithms pick them up and analyse them, leading to slow computation and sometimes incorrect disease diagnoses. Using an enhanced spider monkey algorithm, the team selected the smallest and most informative subset of features that best distinguished healthy leaves from sick ones (bit.ly/monkey-algorithm).

Bansal envisages a larger role for swarm algorithms, especially in autonomous vehicles such as self-driving cars. He believes that future wars will be fought using a fleet of drones, and their success will depend on the performance of bioinspired swarm algorithms. He works with the Indian Air Force to develop such algorithms.

Crisp imaging of fast-moving objects by low-power neuromorphic cameras makes them suitable for diverse applications.

Scientists elsewhere are working on similar concepts. In 2024, researchers from the University of Sussex developed optimisation algorithms based on eavesdropping and altruistic behaviours. In 2022, researchers from the Shanghai-based Donghua University created a Dung Beetle optimiser inspired by the ball-rolling, dancing, foraging, stealing, and reproductive behaviour of the beetles, and used it to optimise the paths of mobile robots.

DEFENCE AND ROBUSTNESS

Bejoy B.J., now an Associate Professor at Bengaluru-based Christ (deemed to be) University, was a research scholar working on intrusion detection systems when he first came across the term artificial immune system (AIS). It is a bioinspired algorithm that copies the principles and workings of vertebrate immune systems to detect and respond to threats in the digital world. A living organism must continually fight microbial threats, and it does so by distinguishing its own cells from those of outsiders and retaining a memory of attacks for later use. Artificial immune systems train an algorithm on the expected behaviour of the digital system so that detectors for standard patterns are eliminated, leaving only those with unusual behaviour. When a threat is detected, the detectors that match the threat pattern multiply and work to eliminate the danger by blocking suspicious processes, quarantining files, isolating network connections, or triggering system-wide alerts. When the danger is eliminated, the successful detector that eliminated the threat is kept in memory to enable a faster response the next time there is a threat.

Such a cyber-secure system is inherently slow, as it must first search for a relevant threat pattern before mounting a response. Bejoy accelerated the system's learning from another set of immune cells, natural killer cells, which look for signals to neutralise threats on their own without wasting time searching for patterns.

This work was done five years ago, and didn't provide information about the kind of attack that had occurred. Bejoy's team is now working to develop a hybrid algorithm which combines this quick natural killer artificial immune system with contemporary machine learning algorithms for intrusion detection, like Recurrent Neural Networks, K-Nearest Neighbor and Random Forest algorithms – that detect threats based on features and patterns so that a memory of the attack is kept in the system (bit.ly/hybrid-algorithm).

OPTIMISING FOR THE BEST

Kusum Deep, a mathematician at IIT Roorkee, was thinking about the pollution in Delhi and wondering whether smog towers could provide some relief. Smog towers clean the air over a large area, and her team sought to identify the most efficient way to install them. Deep knew that a traditional optimisation algorithm that operates in a step-by-step manner would fail to solve this complex problem. The genetic algorithm, which uses the principle of evolution, was better suited to the problem, as it could process various tower designs in parallel, keeping the best and weeding out the others to arrive at an appropriate layout. She developed a new crossover operator for a genetic algorithm that combines two good solutions to produce a better one. Using this operator with a genetic algorithm, her team concluded that 50 smog-free towers were required to reduce pollution by 20-30%, and 188 towers were required to reduce pollution by 35%. They reported this in a 2024 paper (bit.ly/smog-towers).

R&D is not restricted to labs. Many semiconductor giants are now investing in it to help the world shift to energyefficient chips.

Genetic algorithms mimic evolution. As evolutionary forces act on a population of organisms, the genetic algorithm also operates on multiple solutions. As in nature, where the fittest organisms survive, these algorithms also select the best and weed out other solutions. Evolution-inspired algorithms proposed in the 1970s remained largely unused because of the slow computers of the time. Research on such algorithms has increased with the rise of Graphics Processing Units, multi-core Central Processing Units and cloud computing over the years. Another reason for their popularity is the failure of traditional optimisation techniques that require clean mathematical equations. Real-world problems such as traffic control, urban planning, weather forecasting, and complex engineering are messy, with hundreds of variables and even unknown interactions affecting outcomes. Genetic algorithms can wade through this chaos by trying out different solutions and evolving better ones over time. These characteristics of genetic algorithms have been used to develop the National Aeronautics and Space Administration's satellite antennae, the nose of the high-speed Shinkansen Bullet Train, the wing shape of Boeing aircraft, and so on.

ENERGY EFFICIENCY

Another characteristic of biological systems that scientists are trying to emulate in digital systems is their low power. Biological sensors, such as the human retina, process motion and edges using just 1-5 milliwatts (mW), while a conventional camera sensor consumes 1-2 watts, or 1,000 times more energy. Similarly, the human ear detects whispers with just 1mW while microphones and amplifiers require 50-200mW. Sonar systems use 10-100 watts; a bat's echolocation uses tiny sound pulses of 10-100 mW.

Cameras inspired by how the eye functions now use low power. In the eye, photoreceptor cells detect light intensity, bipolar cells calculate changes in light intensity, and on-off ganglion cells are retinal neurons that fire signals when light intensity either increases or decreases, helping the eye detect contrast and edges quickly. In neuromorphic cameras inspired by the eye, photodiodes that perform the work of photoreceptor cells, amplifiers that are analogues of bipolar cells, and comparators that act like on-off ganglion cells. These cameras, which only operate when an event occurs and do not keep recording like standard cameras, ultimately save power. Since they don't wait for frames, fast motion appears crisp, making them ideal for robotics and surveillance.

Chetan Singh Thakur, an Associate Professor at the Bengaluru-based IISc, was fascinated by how fast these cameras can capture a moving object. "If something is moving at 1 metre per millisecond, you will still be able to detect and classify it. Is this a rocket, a missile, or something else? So, it's super useful," he says. His team was interested in the utility of such cameras in astronomy; it attached a camera it had purchased for astronomical observations at the Aryabhatta Research Institute of Observational Sciences (ARIES) in Uttarakhand. The astronomy photographs are currently being taken with Charge-Coupled Device (CCD) cameras, which are better than conventional cameras at detecting dim light, with lower noise and higher accuracy. However, neuromorphic cameras are even better than CCDs, as they capture high-contrast and dynamic scenes faster, use less power, produce less data, and do not blur. CCDs require 60-80 W of cooling hardware to reduce noise; the neuromorphic camera does not require cooling and is thus a low-power alternative for long astronomy observations.

Chetan Singh Thakur's team attached a neuromorphic/event-based camera, purchased from a company called Prophesee, to the 1.3m Devasthal Fast Optical Telescope. Using the neuromorphic camera's high dynamic range — the ability to capture details in both very bright and very dark areas of a scene at the same time — the team was able to capture bright and glowing Saturn with its dim and dull moons: Enceladus, Rhea, Tethys and Dione. They also captured the bright star Sirius A together with the dim star Sirius B in a single frame (bit.ly/event-camera). They also used a similar set-up to capture both bright and faint objects simultaneously by observing Vega, Betelgeuse, and the Trapezium star cluster in the Orion Nebula. When attached to a small-aperture telescope, that is, a 200-mm Dobsonian telescope, the neuromorphic camera was able to detect and capture moving objects, such as meteorites passing near the Moon and Earth, satellites, and anthropogenic debris, without motion blur. Crisp imaging of fast-moving objects by low-power neuromorphic cameras makes them suitable for applications such as autonomous driving, drones, robotics, industrial quality checks on high-speed assembly lines, sports motion tracking, surveillance, and AR/VR eye- and hand-tracking.

His team has also built a silicon cochlea inspired by the real cochlea that can determine whether a sound is coming from the left or the right. Such a system can help track poaching incidents via a network of silicon cochleas. Barn Owls, which can pinpoint the location of their prey in total darkness, have inspired French researchers to develop object localisation systems for dim-light navigation and defence.

Apart from reducing carbon footprint, low-power hardware and software are advancing the field of edge AI, enabling it to run for long periods without heavy batteries. They make portable, wearable, and remote sensors practical in fields such as healthcare, agriculture, and environmental monitoring.

PARALLEL PROCESSING

The current decade has seen the power of brain-inspired algorithms. Artificial neural networks, deep learning, convolutional neural networks, recurrent neural networks, attention mechanisms, and reinforcement learning are the backbone of the AI revolution. However, AI has also exposed the enormous energy demands and inefficiencies of existing hardware to support this revolution. "AI consumes a lot of energy and dissipates a lot of heat, which has made a stronger case for research and development in the neuromorphic hardware," says Ankush Kumar, a material scientist and an Assistant Professor at IIT Roorkee.

Problems such as traffic control, urban planning, and weather forecasting are messy, with hundreds of variables. Genetic algorithms can wade through this chaos.

Large language models run on high-performance but energy-guzzling chips that have separate compartments for computation and memory. Therefore, they spend most of their energy shuttling data between these two compartments. They need to convert every bit of information to 0s and 1s, which also costs energy. This is unlike the brain, where computation and memory are in a single compartment, and signals are of various strengths rather than just 0 and 1.

While scientists have been successful in replicating the brain's ability in software, Kumar believes they need to emulate its structure in hardware. In the brain, each neuron connects with other neurons using branched structures called dendrites, allowing it to compute locally without a central processor. This structure allows for parallel processing, which enables it to operate at high speeds: an important attribute for real-world tasks where the hardware must integrate signals from vision and sound and decisions need to be taken in real-time.

In the last decade, advances in materials science have produced materials exhibiting dendritic characteristics: the ability to grow branches that change with electrical activity, to modify their electrical behaviour gradually, and to remember past signals. Kumar realised that PEDOT (poly-3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene), which conducts like a metal but is as soft as plastic, has attributes to form artificial dendrites. His group showed that the shape, thickness, length, branching pattern, and growth direction of these dendrites could be altered by varying the amplitude and frequency of the electrical current. In a related study, the group has shown that repeated electrical stimulation caused new branches to form and old ones to strengthen or weaken, explaining how entire dendritic networks can physically learn and rewire like the brain (bit.ly/Network-Neural).

These studies showed that learning can be embedded in hardware through electrical stimulation, unlike traditional electronic circuits that cannot change. Using another approach, Sreetosh Goswami, Assistant Professor at the Centre for Nanoscience and Engineering at IISc, is trying to see how brain synapses work by using a tiny device called the memristor that remembers electrical signals passing through it by changing its resistance (see Single set-up, diverse uses). It can thus learn by adjusting its resistance, reducing the need to change software.

The R&D in neuromorphic hardware isn't restricted to laboratories. Many semiconductor giants are now investing in R&D to help the world eventually shift to energy-efficient chips. Intel has developed a brain-inspired hardware system, called Hala Point, with billions of synthetic neurons. IBM is also working on the North Pole neuromorphic system, a brain-inspired accelerator chip that is highly energy-efficient because its memory and computing units are integrated into a single unit. Understanding the brain and how it functions is an area of significant interest not only to neuroscientists but to technologists, too.

See also:

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH