The new sound of music

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 03 issue 02 :: Mar 2024

Craftspeople and engineers are co-creating new avenues and materials for sound production. It's music to our ears.

The sounds of an approaching storm have taken over the SVARAM Sound Garden, but the skies are blue as ever in sunny Auroville. The source of these sounds is a 10-foot cylindrical drum, with a high-carbon steel spring hanging from it. The garden's guide winds up the spring by twisting it to its maximum tension. He then lets it go, generating musical vibrations of a low frequency, amplified by the cylindrical drum surrounding it.

Aurelio C. Hammer, founder of SVARAM - Musical Instruments and Research, has named this instrument the Storm Drum. SVARAM, established in 2003, has been experimenting with — and showcasing — materials producing new sounds. It features instruments such as granite stones that resonate on the application of water, and tubular aluminium bells with long tubes producing deep tones – and short ones producing higher tones.

Before setting up SVARAM, Aurelio had encouraged young men, many of them school dropouts, from neighbouring villages to bring over different materials from their homes and tap on them, leaving the others to guess what the material was. "It was a playful and almost sensory way to explore materials and their acoustics," he says. "Because the foundation of making musical instruments is listening." The Sound Garden today is a draw for visitors to Puducherry.

Aurelio is a luthier, an instrument-maker. Modern-day luthiers are trying to find new avenues of sound production. According to Karan Singh, founder of Bigfoot Guitars, a guitar company based in Goa, there are two schools of thought for instrument-making in India: one that relies on intuition and experience, and one that's more scientific. "Before we select the wood for the guitar, we flex the wood, check for its stiffness and density by tapping it in certain places to hear the kind of resonance that comes out of it. Our experience tells us whether or not it is the right sound," he says.

The modifications may come from experiments in the material used; guitar-making companies have been making guitars out of aluminium and synthetic polymers.

Those led by science follow a different method. "You take the same piece of wood and perform a deflection test. Which means you balance it just on its edges and add a one-kilo weight in the middle to check how much it deflects. You can also use software to determine the frequency at which the wood vibrates. Most great-sounding guitars vibrate at a certain range, so you work backwards from that."

The modifications may come from experiments in the material used, Singh adds. Guitar-making companies in the U.S., such as the Aluminati Guitar Company, have been making guitars out of aluminium, carbon fibres and synthetic polymers. The use of these materials, which are resistant to changes in temperature and humidity, increases the stability of the instrument.

In India, the most commonly used material is the Indian rosewood. Singh experiments with non-traditional woods, including jackfruit, tamarind, certain varieties of mango, and the Indian laurel, which is often to be found in the beams of old Goan houses. "I make my initial decision based on how the grains of the wood look, and how old it is, how dense the growth rings are, how easily it bends, how easy they are to sand, and so on."

THE MODERN CLASSIC

The scientific method has resonated with musicians. In 2019, Chennai-based Carnatic vocalist T.M. Krishna, then working on his book Sebastian & Sons: A Brief History of Mrdangam Makers, met Chandramouli Padmanabhan, Head of Mechanical Engineering at the Indian Institute of Technology Madras (IITM). The rich overtones of the percussion instrument are attributed to the black paste at the centre of its head, which is made of boiled rice, flour and crushed stones. Krishna was interested in understanding how the difference in stones from different regions — Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh — affected the sound.

Krishna approached Padmanabhan, who was at the time working on modifying the mridangam and the veena to make them more portable. Padmanabhan's interests were also personal: his wife is a veena player, and his son, a mridangam player and vocalist.

After a series of tests, Padmanabhan's team found that the mridangam need not be shaped as it traditionally is — with a long cavity at the centre. The one he is developing has two distinct sides which can be carried around easily and then assembled with connecting rods.

"The goal for us is not to go the electronic way or change the acoustic flavour, but to bring engineering principles to make it more amenable to manufacturing, so that more people can take it up," says Padmanabhan, explaining how he wants to reduce the turnover rate for making one mridangam from five days to half a day.

Krishna and Padmanabhan are working closely with mridangam manufacturers and exponents to do blind tests for the sound. They will arrange for experienced volunteers to listen to the modified mridangam from behind a screen, and compare it with a traditional mridangam to see if they sound the same.

"Only then will it be something that can be sold. Because otherwise, there is quite a bit of reluctance among traditionalists to adopt modifications to instruments," Padmanabhan says. "For example, the classical artist will swear by the wood of the jackfruit tree for the mridangam shell, but our engineering analysis has found that the wood has no role to play." On the contrary, Padmanabhan and his team discovered the challenges with wood, after they accidentally left the mridangam shell in the lab when cyclone Vardah hit parts of Tamil Nadu in 2016. The vibrations recorded from that particular instrument were different as the wood had absorbed moisture.

Innovation in instrumentation has happened throughout history, ever since the birth of the first Neanderthal flute, made of bones and considered to be one of the oldest musical instruments. So it is with the mridangam. However, innovation on the mridangam was focused more on the body, from different sizes and shapes of the shell, to octogenarian maestro Umayalpuram K. Sivaraman's glass-shell mridangam.

"We can only grow if we foster universities that have faculty from engineering and music departments across the hall from each other," says Padmanabhan.

"But the experimentation on the membranes of the mridangam is fairly new," Padmanabhan points out. An IITM alumnus, K. Varadarangan, founder of the Bengaluru-based Karunya Musicals, is now creating the mridangam and the tabla with synthetic drumheads, replacing the traditional animal-skin membranes.

Padmanabhan attributes this shift to increased collaboration between academics and musicians. "We can expect more innovation in the next 5-10 years," he says. He himself has been collaborating with several musicians, including leading percussionist N. Guruprasad, who replaced the clay in the instrument with jackfruit wood, and added a signal processing module to cover an entire octave with a single ghatam. "This way, he would not have to change his ghatam based on the vocalist he is performing with," explains Padmanabhan, who is now helping Guruprasad add coatings to the jackfruit wood so that the ghatam keeps resonating even on higher scales.

"Working with open-minded musicians, who do not dismiss ideas, is invaluable," Padmanabhan says. "Today, we rely on chance meetings between musicians and engineers with similar ideas. But we can only grow if we foster universities that have faculty from engineering and music departments across the hall from each other, meeting and ideating together."

BREAKING THE MOULD

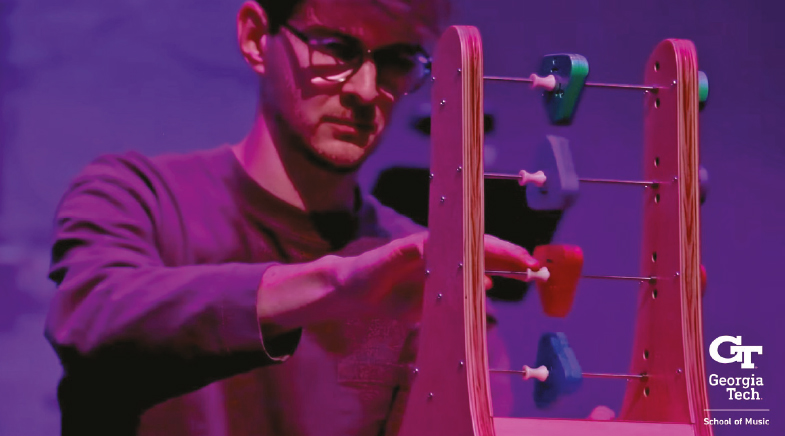

As March rolls on, the annual Guthman Musical Instrument Competition started by the Georgia Tech School of Music in Atlanta, U.S., will see thousands of innovators from around the world showcasing an original instrument that may be the next big thing in music. Although few make it into the mainstream, they still challenge thoughts on how music can be produced. Here are a few of the previous winners.

Synescope

The synescope relies on sonification: it converts colour and reflectance into audio signals. Inventor Brian Alexander was inspired by his condition of synesthesia, which makes him perceive a tonal quality to materials such as stones.

PHOTO: BRIAN ALEXANDER

Electromagnetic piano

Pianist Monica Lim displayed her electromagnetic piano, a magnetic unit operated by a microcontroller to be attached to any grand piano. Each string has a magnet tuned to its frequency, allowing it to sustain vibrations.

PHOTO: MONICA LIM

Abacusynth

Created by Brooklyn-based web developer Elias Jarzombek, the abacusynth explores the building blocks of audio synthesis. Four metal rods with wooden blocks, which can be slid, function as oscillators tuned to harmonic frequencies.

PHOTO: GEORGIA TECH

Yaybahar

This acoustic instrument was developed by Turkish musician Görkem Şen in 2014. Primarily a string instrument played with a wooden bow, the yaybahar carries forward vibrations from the strings to frame drums via coiled springs, resulting in ethereal sounds straight out of science-fiction cinema.

PHOTO: GÖRKEM ŞEN

See also:

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH