When the chemistry was just right

-

- from Shaastra :: vol 01 issue 04 :: Jul - Aug 2022

These chemists made fundamental contributions to their field, and had an impact on India.

The beginnings of chemistry in India are often traced to P.C. Ray in West Bengal. Ray established a school of chemistry in Presidency College in Calcutta, and his work on nitrites brought him international recognition. Ray was also India's first scientist-entrepreneur. The next milestone was the establishment of the Indian Institute of Science, where chemistry was among the first departments to be set up. Compared to the state of chemistry in Europe, these were small steps. The true pioneers of modern chemistry in the country were T.R. Seshadri and K. Venkataraman, both of whom studied at Presidency College in Madras initially, and were professional rivals. They also did their PhD research under the same scientist, Nobel Laureate Robert Robinson.

When they returned to India, Venkataraman joined the fledgling University Department of Chemical Technology (UDCT) and Seshadri went to Andhra University. They nurtured their fields in both these institutions before moving on to the National Chemical Laboratory (NCL) and Delhi University, respectively. After India became independent, Delhi University, NCL and UDCT became major centres of research in chemistry. Seshadri and Venkataraman could be regarded as the first generation of chemists in independent India, with a focus on synthetic organic chemistry.

Two more major chemistry hubs came up in the next generation, with T.R. Govindachari at Presidency College in Madras, and Asima Chatterjee in Calcutta. Meanwhile, chemistry was changing as a discipline, with quantum mechanics driving the creation of new theoretical and experimental methods. C.N.R. Rao at IIT Kanpur became the leader in this line of research, focusing largely on materials. The Chemistry Department at IIT Kanpur in the 1960s had other stars as well — P.T. Narasimhan and M.V. George, to mention two — to whom students were drawn like magnets from all over India.

Over the next 50 years, a large number of chemists from these departments left academia to create chemical and pharmaceutical industries. Until the mid-1990s, import restrictions made life difficult for academic chemists. Liberalisation lifted some of these restrictions, but only a small number of scientists have been able to make a mark on the global scene. We pick some of them here, looking at either their fundamental contributions to their field or their impact on India. In rare cases, in both ways.

ASIMA CHATTERJEE

One of Asima Chatterjee's many claims to public fame is that she was one of the earliest women in India to get a doctorate. Beyond this, she was one of India's pioneers in chemistry, belonging to a small group of second-generation chemists after independence.

Chatterjee was born in Calcutta in 1917 and studied chemistry at the University of Calcutta, ultimately getting a DSc in 1944.

During her research, she got to work with P.C. Ray on natural product chemistry. She also worked with P.K. Bose, a chemist who was among the first to do research on natural products. She was appointed an honorary lecturer at the university. But Chatterjee, who was married by then, went to Wisconsin for postdoctoral research, taking her 11-month-old baby with her.

After working with Nobel Prize winner Paul Karrer in Zurich, she returned to join Lady Brabourne College in Calcutta, and later became Reader at the university. Her work with Karrer had sharpened her interest in natural products.

In 1962, she became the Chairperson of the Chemistry Department, the first woman in India to be appointed Chair in any field.

Like all chemists of her generation, she had to struggle for funds. But she developed drugs for malaria, epilepsy and cancer, and left an indelible imprint on the country and its people.

K. VENKATARAMAN

Krishnaswamy Venkataraman was born in 1901 in a family of scholars in Madras. He studied at Presidency College and then went on a scholarship to Manchester University to study under Robert Robinson. After returning to India, he worked for some time at the Forman Christian College in Lahore, from where he published his first major paper, on the synthesis of the plant pigment flavones, in Current Science, then a new Indian journal started by C.V. Raman. Around the same time, independently, British chemist Wilson Baker published a paper in the Journal of the Chemical Society outlining a similar synthesis. The reaction described in these papers is now called Baker-Venkataraman rearrangement. It has important applications in the synthesis of flavones, and is still the only reaction named after an Indian chemist.

Venkataraman later moved to Bombay and joined UDCT, where he subsequently became its first Indian Director. Venkataraman brought scientific research to a technology institute, a culture that remains strong in the institution. On the other hand, he also emphasised practical aspects of research. Over a period, UDCT had a major impact on the Indian chemical industry by creating a large number of entrepreneurs and supplying technology to private companies. After retiring from UDCT, Venkataraman moved to NCL, becoming its first Indian Director.

T.R. SESHADRI

T.R. Seshadri's career somewhat mirrored K. Venkataraman's, especially in the early years. Seshadri, a year younger than Venkataraman, was also born in the Madras Presidency but in a small town near Tiruchirappalli. He, too, studied at Presidency College. After a Master's degree from the University of Madras, Seshadri went to the University of Manchester on a Madras government scholarship. His PhD research with Robert Robinson was on antimalarial drugs and anthocyanins, compounds that colour vegetables bright red and purple. After stints in other European labs, Seshadri joined Andhra University at Waltair.

Within a short time, he'd built a school of chemistry at the university; it became a major centre for research on flavonoids. The army took over his lab during the Second World War, and Seshadri had to move to Madras. After India became independent, Seshadri joined the University of Delhi. Within a few years, he had established another school of chemistry centred on natural products, to which researchers came from Europe for postdoctoral research. By the time of his death in 1975, he had trained more than 150 students and published 1,000 papers. By any yardstick, Seshadri was the pioneer in the synthesis of natural compounds.

SUKH DEV

After K. Venkataraman moved to NCL as its Director, the laboratory began to attract talented chemists. By the 1960s, it had a fair concentration of chemists with a reputation. The two prominent chemists among them were S.C. Bhattacharyya and Sukh Dev. Both worked on natural products, and both first established their careers at the Indian Institute of Science. Both moved from NCL before their retirement — Bhattacharyya to IIT Bombay, and Sukh Dev to the Malti-Chem Research Centre in Nandesari. Sukh Dev returned to academia in 1989: he joined IIT Delhi and then University of Delhi.

Sukh Dev's research centred on terpenoids, a class of molecules not generally essential for growth but useful to a plant. They make plants brightly coloured and have medicinal properties. He worked out the structure of a large number of terpenoids and also found the active ingredients of some Ayurvedic formulations. Many of these molecules are complex and it is hard to determine their structures, especially by using the methods of the 1950s. Sukh Dev was one of the early scientists who began to look for active ingredients in Ayurvedic formulations. He also trained a large number of students, some of whom became prominent scientists themselves.

B.D. TILAK

B.D. Tilak had worked under some of the best chemists in the world: K. Venkataraman at UDCT, Robert Robinson at Oxford and Robert Woodward at Harvard, considered the best organic chemist of the previous century. After his postdoctoral stint abroad, Tilak returned to UDCT where he inspired students with dazzling lectures. His research over the next ten years established India's dyestuff industry. It was an unusual phenomenon in the 1960s for an academic institution to produce entrepreneurs with such regularity. Tilak became the UDCT Director after Venkataraman moved to NCL.

When Venkataraman retired as NCL Director, Tilak took his place. He had especially been sought out by the government to bring the lab closer to industry. By the time he retired in 1978, he had changed the institute by focusing on import substitution and indigenous technology development. He understood the concepts of project engineering and technology readiness, and got NCL to develop technology for manufacture in tonnes rather than in grams, making the lab a pioneer in industrial technology development.

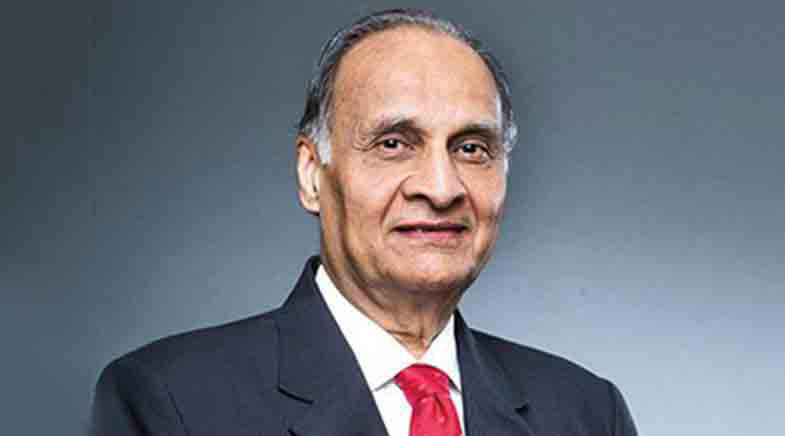

GOVERDHAN MEHTA

Goverdhan Mehta was a PhD student of Sukh Dev, who was one of the pioneers of natural products chemistry in India. Mehta was fascinated by colours, aromas and the beautiful 3-D structures that organic molecules produced. He liked organic molecules also because they provided a wonderful expression of art at a molecular level. Throughout his professional life, he used to work like an architect, creating aesthetically pleasing molecular structures, using simpler molecules like bricks. Such structures were not always built with an application in mind, but some of them did turn out to be useful.

After securing his PhD from the University of Pune, Mehta joined the Chemistry Department of the Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur. He subsequently worked at the University of Hyderabad, where he became the Vice Chancellor, and at the Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore, where he was the Director for seven years. His group did the total synthesis of 50 biologically active compounds, introducing many new names — garudane, golcondane, ladderane — into chemical literature. Some of his techniques are known as early examples of green synthesis.

His work also led to development of hybrid drugs for the treatment of cancer; these combine the drugs' conventional cytotoxic action with the ability to switch on in the desired location using light as a stimulus. Certain carbon compounds that his group synthesised have potential applications in nanotechnology. As the Director of IISc, he had created many new programmes, including a policy for faculty to set up companies.

DARSHAN RANGANATHAN

Darshan Ranganathan was one of India's best chemists of the previous century. Yet, she was not offered a faculty position at IIT Kanpur, on the grounds that her husband Subramania Ranganathan was a Professor there. She had to wait for a regular job at an institution till her husband retired in 1993, when she joined the Regional Research Laboratory (RRL) in Trivandrum. There she had a full-fledged laboratory and other facilities that scientists usually have access to, and she entered a prolific phase in her career. She moved to the Hyderabad-based Indian Institute of Chemical Technology (IICT) in 1998, a lab with better facilities than RRL; she flourished there even more than she did at RRL.

Ranganathan had done her PhD with T.R. Seshadri at Delhi University. Her subsequent work focused on looking at nature and reproducing the ways molecules are made. She had developed a fascination for mimicking nature in the lab early in her career. She had created many such steps in her lab, working on molecules such as imidazole, citrulline, and large peptides. She died of breast cancer in 2001. In the last five years of her life, she had published 11 papers in the Journal of the American Chemical Society and six in The Journal of Organic Chemistry, an astonishing level of productivity and quality that few in the country could match.

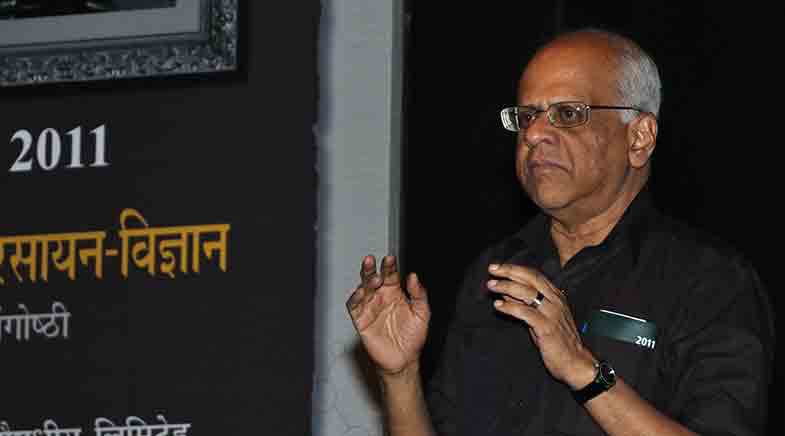

GAUTAM DESIRAJU

Gautam Desiraju joined the University of Hyderabad in 1979. He had a PhD in structural chemistry from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. After a short stint at Eastman Kodak in Rochester, Desiraju returned to India, and started work at Hyderabad University. The experimental facilities at the university, established in 1974, were rudimentary. Desiraju found that he did not have the equipment to do his research on crystal structures. Specifically, he did not have a single-crystal X-ray diffractometer, an instrument that would provide detailed information about crystal structures such as the size of repeating units, bond lengths and bond angles. It is a common instrument in such labs, but Desiraju would not have it for another 20 years.

He decided to use facilities abroad for his work. He would take samples, send them to laboratories abroad for diffraction data, and then analyse them. Working in this manner, Desiraju developed a name in the field of crystal engineering. Specifically, he figured out the role of weak hydrogen bonds in how molecules assemble to form crystals. He also developed the idea of a supramolecular synthon, the idea of creating organised assemblies from small units. Desiraju is one of the most cited chemists in India and was the President of the International Union of Crystallography.

C.N.R. RAO

By all means, C.N.R. Rao is India's most influential scientist in its 75 years of independence. He was the most prolific, publishing over 1,700 publications and writing and editing over 50 books. He also trained more than 150 students in research. He had a career spanning 60 years, during which he raised the profile of Indian science among bureaucrats and politicians. Indirectly, through tireless lobbying, he helped create structures for funding science on a regular basis. He created a flourishing Chemistry Department at IIT Kanpur and the Solid State Chemistry Department at IISc. He restructured IISc as its Director, and created a new, high-quality institute in the Jawaharlal Nehru Centre for Advanced Scientific Research.

This summary does not do justice to Rao and his contributions to his field or the country. Like many scientists of his generation, Rao chose to come to India after his PhD, leaving institutions abroad with the best of facilities for Indian institutions that had no facilities for research in his field. Rao's struggles and his triumphs mirror those of many in the 1960s and 1970s. They could not choose problems that they would have worked on, if they had been in the U.S. or Europe. Instead, they created strategies on building a career with the existing resources, often innovating in different ways to create those facilities. Rao's strategy was to pick a field — solid state materials was one of his early choices — that was beginning to form and then produce an explosion of research that would expand it significantly. It brought him worldwide attention and all awards except the Nobel Prize.

See also:

These scientists were also institution builders

Physicists who made quite a mark

These engineers foresaw the future

They shaped the development of indigenous technology

Have a

story idea?

Tell us.

Do you have a recent research paper or an idea for a science/technology-themed article that you'd like to tell us about?

GET IN TOUCH